How to Eat Like a King for Christmas

Using antique technology and vintage cookbooks, food historian Ivan Day recreates such Tudor and Victorian specialties as puddings and roast goose

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/historic-holiday-foods-631.jpg)

From the kitchen window of Ivan Day’s snug 17th-century farmhouse in the far north of England, snow blankets the bald Cumbrian hills of Lake District National Park.

“Just look,” he chuckles, “You’re going to have a white Christmas early.” It’s the last time we will mention the weather.

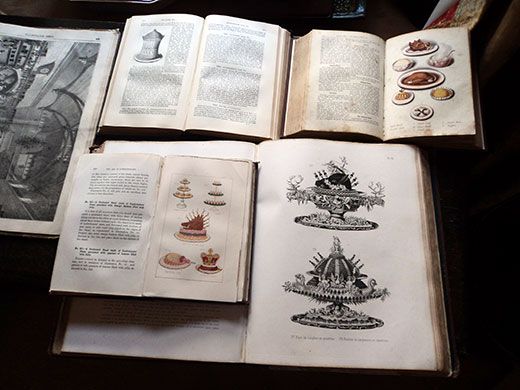

But it’s only the beginning of our concentration on Christmas. Two weeks before perhaps the biggest feast day in the Christian realm, I’ve flown through a hurricane-strength gale and driven white-knuckled for hours on icy rural roads to reach Day, one of England’s most esteemed food historians. Twelve to 15 times each year, he teaches courses in historic cookery, allowing students access to his 17th-century pie molds and 18th-century hearth to recreate repasts of the past. His two-day historic food lessons range from Italian Renaissance cooking (spit-roasted veal and a quince torte made with bone marrow) to Tudor and Early Stuart cookery (herring pie and fruit paste) for a maximum of eight students. But in late November and early December, Christmas is on the table.

At Christmas, as in much of food history, he says, “What you find are the traditions of the aristocracy which filtered down from above. Everybody wanted what Louis XIV was eating.”

The same could be said today. From the bar to the back booths, nostalgia is on the rise in trend-setting restaurants. In Chicago, chef Grant Achatz of Alinea fame recently opened Next restaurant with quarterly menus that channel specific cultures and times, such as Paris circa 1912. In Washington D.C., America Eats Tavern from chef José Andrés prepares Colonial-era recipes. And in London, chef Heston Blumenthal runs Dinner restaurant with a menu composed entirely of dishes from the 14th through 19th centuries, such as savory porridge made with snails.

When chefs or curators, such as those at the Museum of London, need an authority on historic food, they turn to Ivan Day. A self-taught cook, Day has recreated period dishes and table settings for foundations such as the Getty Research Institute and television programs on the Food Network and the BBC. His food, including a larded hare and flummery jellies, is the centerpiece of “English Taste: The Art of Dining in the Eighteenth Century,” at the Houston Museum of Fine Arts through January 29, 2012.

Inside his white-washed cottage, just off the frost-covered kitchen garden, a blazing hearth warms the beamed, low-ceilinged workroom ringed in Day’s personal collection of food molds for everything from towering meat pies to single-serving jellies. A cross-section of English collectors and cooks has assembled here including a retired antiques dealer who carries a photo album of recently purchased antique cookware; a university department head and avid pastry maker; a winner of a reality TV cooking show, now teaching nutrition; and a former caterer.

“The earliest Christmas menu that we know is from the 17th century and describes white bread for Christmas,” begins Day. “If you were lowly, that might be your only treat.”

But if you were king in 1660, for the Christmas Day bill of fare, you might enjoy 20 dishes, including mutton broth and stuffed kid, for the first course alone. The second course on a historic menu listed 19 dishes, including “swan pye” or pie made with the waterfowl featuring a taxidermied bird atop the crust.

Our class will survey holiday dishes ranging from a modern-looking composed green salad circa 1660 to a Victorian plum pudding. We will create three meals over the course of two days that combine lessons in art, antiques and technology as much as cooking.

Standing between the fire and a dark wooden worktable, Day displays a cleaned 12-pound goose atop a cutting board. Next to it are large glazed ceramic bowls of premeasured ingredients for stuffing, a.k.a. pudding. The kitchen looks like the setting for a Tudor-era cooking show. The recipe is vague, calling for two handfuls of bread crumbs, an onion boiled in stock, sage leaves and a handful of suet, a hard fat that wraps a cow’s kidney and is sold, crumbled in England and will clearly be my first procurement hurdle stateside.

But it’s far from the last. The key to the roast goose is the hearth, an 18th-century iron fireplace inset with a shallow coal chamber roughly three feet tall reaching temperatures that chase us to the far, drafty end of the room.

“There’s plenty of fowl in this country. And coal gave us great roasting,” says Day, who calls himself a “barbecue man” out of affection for his hearth. “But you don’t roast over a fire, you roast in front of the fire.”

There we dangle the bird, stuffed, pinned together with a pewter skewer and trussed in string, for the next two hours, alternatingly spun three times clockwise and another three time counterclockwise by a jack developed by clockmakers in the 1700s. Fat immediately begins to trickle down, flavoring parboiled potatoes heaped in a dripping pan below.

Day next delegates a student to grind pepper in an antique wooden mortar for more pudding. “I bought this when I was 14,” he smiles. “That’s when I started my unhealthy interest in period cookery.”

It was the year prior, at 13, when he discovered John Nott’s The Cooks and Confectioners Dictionary, written in 1723. Within six months he had acquired 12 other period cookbooks and by his mid-20s he owned a library of more than 200 from which he taught himself to cook. “All of my teachers died 400 years ago,” he says.

A former botanist and former art teacher, Day considers historic food a lifelong passion and, for the past 20 years, a third career. The 63-year-old, with the scarred hands of a chef and the glinting eyes of a storyteller, combines an encyclopedic memory with the opinionated wit of a crusading academic. He also has talent for impersonation and does a spot-on Martin Scorsese phoning to ask if he will consult on the food for a film he helped produce, Young Victoria (Day agreed to do so). In teaching, he says over lunch of our now finished and succulent goose, “I’m interested in getting people in this country to be more inquisitive about their food culture. The vast majority of people are eating cheap food from stalls.”

Back in the day, according to the historian, selection was surprisingly great. Many of the luxury ingredients found in holiday dishes, such as almonds, currants, citrus and raisins, derive from the Islamic world, brought west in the Middle Ages with returning Crusaders. Several centuries later, peddlers roamed the countryside with sacks of spices like nutmeg and recipes called for exotics such as cassia buds, an aromatic spice related to cinnamon. “The variety of ingredients I’ve discovered is much wider than what we have now,” says Day. “In the 18th century in [the nearby village of] Penrith a woman could buy ambergris [a solidified whale excretion used as a flavoring agent], mastic [a gum used for thickening] and a half-dozen other things.”

Many of them make their most acclaimed appearance in plum pudding, the iconic English dessert that was mentioned as a Christmas treat in the 1845 book Modern Cookery and immortalized in Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol featuring a nervous Mrs. Cratchit serving her version to the family’s ultimate delight.

Like other savory puddings, this one starts with bread crumbs and suet. Reaching for another generous bowl, Day breaks into a hearty English ditty,

“Plum pudding and pieces of pie,

My mother she gave me for telling a lie,

So much that I thought I should die,

For lumps of plum pudding and pieces of pie.”

We mix in currants, raisins, cloves, diced ginger and preserved orange peel and bind it with eggs, resulting in a wet, dense ball that Day declares “perfect for shot-putting.” Instead we push it into a Victorian-era greased “kosiki” mold, which resembles a castle with a central tower and four surrounding cupolas, where it will be boiled in a pot of water.

With their mix of prosaic and exotic ingredients, holiday puddings were the sorts of dishes the nobility would prepare for the poor on Christmas, doing their benevolent duty on a day that still celebrates hospitality and neighborliness.

“I call myself a culinary ancestor worshipper. It’s all about the people. There are voices from the past trying to explain how to do it.” He adds, “technology is the key.”

Turning our attention to dinner, we prepare a horizontal “cradle spit” caging an eight-pound standing rib roast rigged to a wind-up jack advanced by a slowly descending iron ball. “This is the sound of the 18th-century kitchen,” proclaims Day of the creaking cadence that will pace us over the next several hours while we construct a Christmas pie.

Though pies most often connote dessert today, their savory incarnations were an early form of food preservation. Meat pies could be cooled, drained of their juices via a hole carefully cut into the bottom of the pastry, and refilled with clarified butter, keeping without refrigeration for three months or more, like a canned good.

For our Christmas pie, we employ an elliptical-shaped, six-inch-tall mold with a nipped waist, fluted sides and hinged ends, lining it in pastry crust. Next we fill it with an assortment of poultry – “We tend to eat birds at Christmas when wild food is at its best, its plumpest” – layering in seasoned ground turkey with the breasts of turkey, chicken, partridge, pigeon and goose. Topping it with crust, we decorate the lid with pastry cut from fern-shaped wooden molds and form a rose of pastry petals.

Like pre-20th-century fashion, frippery was in vogue at the table. “Food has a visual aesthetic that reflects the aesthetics of the time,” says Day. “Now we are in an age of abstract modernity with splashes of this and that on the plate.”

Greeting us after a three-hour break before Christmas dinner—take two—is a hot brandy and lime punch with orange peels dangling out of the bowl. It’s the first recipe I feel confident I can replicate at home without scouring an antiques store. In the meantime, Day has prepared a plum pottage, a meat and fruit soup he calls “liquid Christmas pudding.” The 1730 recipe went out of fashion under the influence of King Louis XIV of France. “French cooking in the 17th and 18th centuries changes from cooking meat with fruit, which is of Islamic origin. They renounced sweet and sour flavors and elevated meaty, earthy flavors.”

In addition to its delectability, class time includes instruction in antiques, illustrated by our next morning’s attempt at a 1789 recipe for ice cream. Using a lidded pewter cylinder known as a sorbettier, we fill it with cream, simple syrup, preserved ginger and lemon juice and let it rest in a bucket of salt and ice outdoors in the drizzle of Sunday morning. Spun and stirred occasionally, it freezes about 20 minutes later. Spooned into a mold with layers of sponge cake and candied fruit, it becomes an “ice pudding.” With the remainder, we employ a seau à glace, a delicate 18th-century serving dish featuring a separate bowl that nests in a compartment for ice and salt topped by a lid designed to hold additional ice. Though it sits on the counter at room temperature for over an hour before lunch, the ice cream remains solid, a finale to the gorgeously striated poultry pie, now baked and sliced.

“When you start unraveling its function, you understand an object much more,” says Day, dishing ice cream onto plates and urging us to take seconds: “Christmas only comes but once a year.”

Unless you’re Ivan Day, for whom Christmas has been the subject of five lectures, two cooking courses and numerous television and radio appearances. For his own upcoming holiday, he plans a much simpler celebration. “All I want for Christmas,” he laughs, “is a digestive biscuit and a cream of cocoa.”

Elaine Glusac is a writer based in Chicago who specializes in food and travel.