How to Install a 340-ton Work of Art

Michael Heizer waited decades to find the perfect rock for his Levitated Mass, and now he awaits its slow journey from the quarry to an L.A. art museum

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Levitated-Mass-installation-631.jpg)

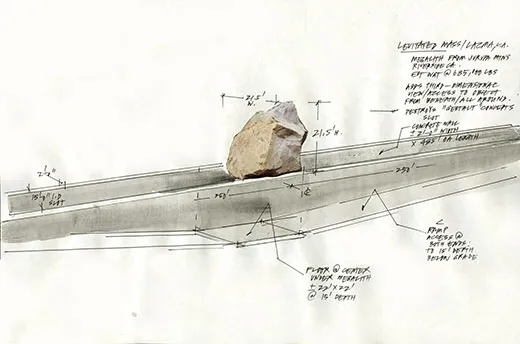

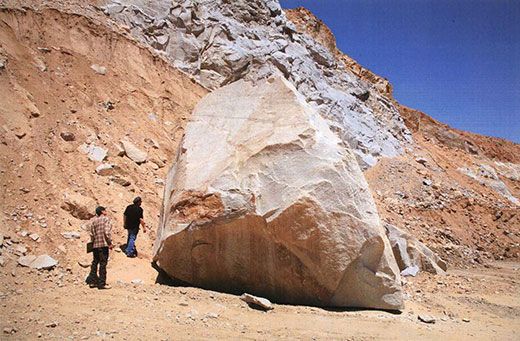

A pioneer in monumental artworks made of earth and stone, Michael Heizer had waited 40 years for the perfect rock for one of his projects. It was 1968 when he first conceived of a large-scale work that would suspend a giant boulder over a trench cut in the earth. Four decades later at a stone quarry in Riverside, California, Heizer spotted his prize—a pyramid-shaped, 340-ton chunk of granite that had been dynamited from a cliff. He proclaimed it “the most beautiful rock I’ve ever seen.” In a few weeks, the piece he designed so long ago, called Levitated Mass, will be installed at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art with the 21-foot-high monolith as its crowning centerpiece.

Obtaining the work was a coup for the museum’s permanent collection, says LACMA’s director, Michael Govan, who is committed to expanding the museum’s holdings beyond framed paintings in white-walled galleries. “Because of our unique location in the center of Los Angeles but within 20 acres of parkland, we can create a unique indoor/outdoor setting for monumental art,” he explains. LACMA is already home to large-scale sculptures by such acclaimed artists as Tony Smith, Richard Serra and Chris Burden and can well accommodate Heizer’s mammoth work.

“This piece is perfect for LACMA because we are an encyclopedic museum,” Govan says. “It is a series of opposites: positive and negative, linear and more or less spherical, weight and emptiness, civilization and geological times, geometry and the organic, regular and irregular, and ancient and modern. The piece frames time.”

Govan worked with Heizer during the installation of the artist’s North, East, South, West —four huge geometric sculptures of weathering steel sunk 20 feet beneath the gallery floor —at DIA: Beacon in New York. Heizer’s new work has “echoes of ancient monuments but is invested in present human experience,” Govan says. “In that way it is utterly modern.” Levitated Mass is to be installed on a two-and-a-half-acre site on the museum’s north side; opposite, on the south end, is Burden’s Urban Light, a sculpture incorporating 202 restored antique cast-iron lampposts that once lit Los Angeles streets. Museumgoers are not expected to passively observe Levitated Mass. As visitors walk through the 456-foot-long concrete-lined channel that descends 15 feet into the ground, the boulder, resting on steel and concrete supports, will have the appearance of floating or levitating above their heads. It’s bound to be awe-inspiring and probably tinged with an element of danger.

If all goes well, Levitated Mass will open to the public in late November, but at this writing the boulder hasn’t left the quarry, which is about 60 miles from the museum. The logistics of transporting such a large rock have been profound. The ancients moved monoliths with far cruder technology than that available today. Getting permits, however, from the various municipalities on the route to Los Angeles has postponed the boulder’s departure numerous times as officials review potential hazards. The weight alone could overburden the roads. It can’t be taken over bridges. As tall as a two-story house, the rock could take down power lines once it’s loaded on the 270-foot-long rig specially designed to haul it. Navigating the grid of city streets seems nightmarish.

To address these challenges, LACMA commissioned Emmert International, a specialist in transporting heavy objects. Project supervisor Rick Albrecht shrugged off any suggestion that this is an unusual job. “We've moved big transformers that weighed about 1.2 million pounds, so this shouldn’t be a problem,” he said, standing in the dusty quarry, while behind him workers assembled the enormous transport vehicle around the boulder. The rig’s perforated red beams resemble a giant segmented insect. It is the width of three lanes of traffic and will ride on nearly 200 tires. Its modular design will facilitate turning corners.

The weight of the boulder is comparable to other projects Emmert has handled, Albrecht says, but the rock’s irregular shape and the permitting processes have kept it grounded. Once the paperwork is cleared, the transport rig will be accompanied by police escort and trucks and proceed at five miles an hour, but only at night to avoid disrupting traffic. Special daytime parking arrangements for the heavy load have to be worked out with towns along the route. The trip is expected to take nine nights.

While the transport itself has been stalled, building the channel has had its own difficulties. Though a marvel of artistic vision and engineering, it still had to comply with building codes, seismic safety standards and handicap accessibility. Contiguous to the archaeologically important La Brea Tar Pits complex, the site was also scouted for fossils during excavation.

Despite the delays, the estimated $10 million exhibition is worth the wait. Thousands of people will be able to visit the work of an artist who has influenced much of the public large-scale land art movement of the late 20th- and early 21th-centuries right in the heart of Los Angeles. Levitated Mass will inscribe itself onto the environment, inviting people to experience the intersection of modern and ancient. It will be a primordial reminder of our time and place, and of our power and vulnerability.