How to Trademark a Fruit

To protect the fruits of their labor and thwart “plant thieves,” early American growers enlisted artists

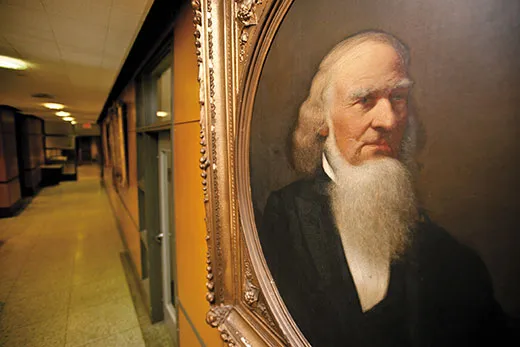

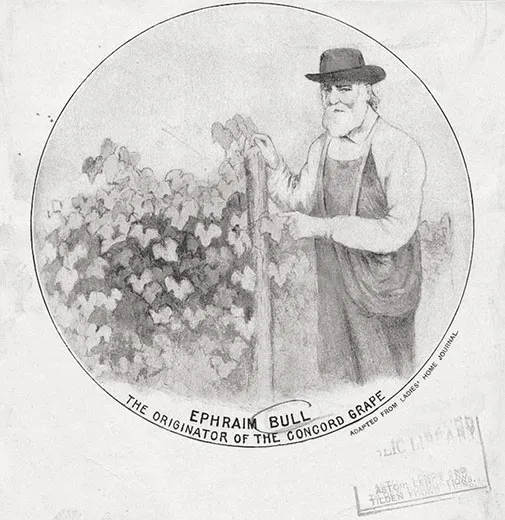

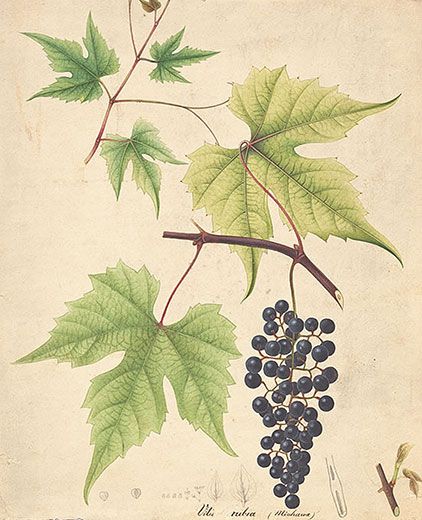

In 1847, Charles M. Hovey, a stalwart of the Massachusetts Horticultural Society and the proprietor of Hovey & Co., a 40-acre nursery in Cambridge, began publishing a series of handsomely illustrated prints of American fruits. Most of the trees—apple, pear, peach, plum and cherry—had come from England and Europe. Over time, many new fruit varieties emerged from natural cross-pollinations effected by wind, birds and insects—for example, the Jonathan apple, after Jonathan Hasbrouck, who found it growing on a farm in Kingston, New York. By the mid-19th century, a few new indigenous fruit varieties had arisen from breeding, notably Hovey’s own widely admired seedling strawberry and the prizewinning Concord grape, a recent backyard production of Ephraim Bull, a neighbor of Ralph Waldo Emerson.

At the time, regional and national agricultural markets were emerging, aided by steamboats, canals and railroads. The trend was accompanied by expansion in the number of commercial seed and nursery entrepreneurs. State horticultural societies dotted the land, and in 1848, several of their leaders in the Eastern states initiated what became the first national organization of fruit men—the American Pomological Society, its name drawn from Pomona, the Roman goddess of fruits. Marking these developments, in 1852 Hovey gathered his series of prints into a compendium called The Fruits of America, Volume 1, declaring that he felt “a national pride” in portraying the “delicious fruits...in our own country, many of them surpassed by none of foreign growth,” thus demonstrating the developing “skill of our Pomologists” to the “cultivators of the world.” Further evidence of their skill came with publication of Volume 2, in 1856.

I first came across Hovey’s book while researching the history of new varieties of plants and animals, and the protection of the intellectual property they entailed. In the mid-19th century, patent protection did not extend to living organisms as it does now, when they are not only patented but also precisely identifiable by their DNA. Still, fruit men in Hovey’s era were alive to the concept of “intellectual property.” Operating in increasingly competitive markets, they offered new fruits as often as possible, and if they were to protect their property, they had to identify it.

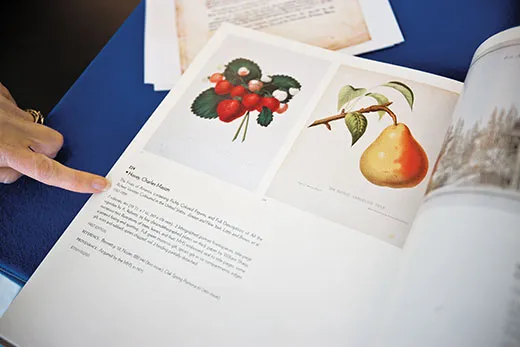

Hovey’s aims transcended celebration. He published the illustrations so the fruits could be reliably identified by growers as well as sellers, and especially by the innovators who first brought them out. I discovered upon further digging—in nursery catalogs, handbooks and advertisements—that his effort exemplified the beginnings of a small industry of fruit illustration that was an integral part of the pomological trade in the latter half of the 19th century. And much of it, while produced for commercial purposes, was aesthetically arresting. Indeed, it combined traditional techniques and new technology, leaving us a large, often exquisite body of American botanical art.

The need for pictures was prompted by the proliferation of fruit names that accompanied the multiplication of varieties. Fruits in the United States were bought and sold under a riot of synonyms, creating, Hovey noted, “a confusion of nomenclature which has greatly retarded the general cultivation of the newer and more valuable varieties.” One popular apple, the Ben Davis, was also called Kentucky Streak, Carolina Red Streak, New York Pippin, Red Pippin, Victoria Red and Carolina Red. William Howsley, a compiler of apple synonyms, called the tendency of “so many old and fine varieties” to be cited in horticultural publications under new names “an intolerable evil, and grievous to be borne.”

Variant nomenclature had long plagued botany. Why now such passionate objections to the proliferation of synonyms, to a mere confusion of names? A major reason was that the practice lent itself to misrepresentation and fraud. Whatever their origins—hybrids, chance finds or imports—improved fruits usually required effort and investment to turn them into marketable products. Unprotected by patents on their productions, fruit innovators could be ripped off in several ways.

In the rapidly expanding nursery industry, a good deal of seedling stock was sold by small nurseries and tree peddlers, who could obtain cheap, undistinguished stock, then tell buyers it was the product of a reliable firm or promote it as a prized variety. Buyers would be none the wiser: a tree’s identity often did not become manifest until several years after planting.

Fruit innovators also suffered from the kind of appropriation faced by today’s originators of digitized music and film. Fruit trees and vines can be reproduced identically through asexual reproduction by grafting scions onto root stock, or by rooting cuttings directly into soil. Competitors could—and did—purchase valuable trees, or take cuttings from a nursery in the dead of night, then propagate and sell the trees, usually under the original name. A good apple by any other name would taste as sweet.

Nurserymen like Hovey founded the American Pomological Society in no small part to provide a reliable body of information about the provenance, characteristics and, especially, names of fruits. The society promptly established a Committee on Synonyms and a Catalogue, hopeful, as its president said, that an authoritative voice would be “the best means of preventing those numerous impositions and frauds which, we regret to say, have been practiced upon our fellow citizens, by adventurous speculators or ignorant and unscrupulous venders.”

Yet the society had no police power over names, and its verbal descriptions were often so inexact as to be of little use. It characterized the “Autumn Seek-No-Further” apple as “a fine fruit, above medium size; greenish white, splashed with carmine. Very good.”

Drawings and paintings had long been used to identify botanical specimens, including fruits. During the early 19th century in Britain and France, heightened attention was given to the practice of illustration in response to the proliferation of different names for the same fruits. An exquisite exemplar of the genre was the artist William Hooker’s Pomona Londinensis, the first volume of which was published in London in 1818. But beautiful as they were, pictorial renditions such as Hooker’s did not lend themselves to the widespread identification of fruits, even in small markets, let alone the steadily enlarging ones of the United States. Hooker’s illustrations were hand-painted. Such paintings, or watercolored lithographs or etchings, were laborious and expensive to produce and limited in number.

But in the late 1830s, William Sharp, an English painter, drawing teacher and lithographer, immigrated to Boston with a printing technology that had been devised in Europe. It promised to enable the production of multiple-colored pictures. Called chromolithography, it involved impressing different colors on the same drawing in as many as 15 successive printings.

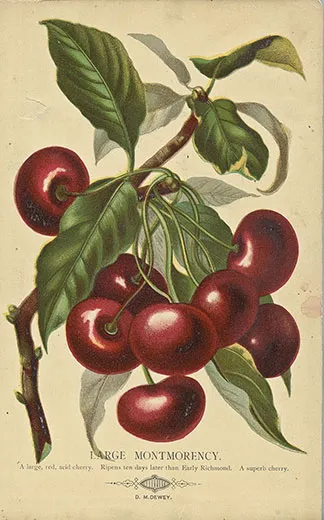

Charles Hovey enlisted Sharp to produce the colored plates in Fruits of America, declaring that his “principal object” in publishing the work was to “reduce the chaos of names to something like order.” Together, the two volumes included 96 colored plates, each handsomely depicting a different fruit with its stem and leaves. Hovey held that Sharp’s plates showed that the “art of chromo-lithography produces a far more beautiful and correct representation than that of the ordinary lithograph, washed in color, in the usual way. Indeed, the plates have the richness of actual paintings, which could not be executed for ten times the value of a single copy.”

Not everyone agreed. One critic said that fruit chromolithographs lacked “that fidelity to nature, and delicacy of tint, which characterize the best English and French coloured plates, done by hand.” Some of the illustrations did appear metallic in tone or fuzzy, which was hardly surprising. Chromolithography was a complex, demanding process, an art in and of itself. It required a sophisticated understanding of color, the inventive use of inks and perfect registration of the stone with the print in each successive impression.

The editors of the Transactions of the Massachusetts Horticultural Society, who had tried chromolithographs and been disappointed, resorted to a prior technique—black-and-white lithographs that were then watercolored by hand. The editors engaged an artist named Joseph Prestele, a German immigrant from Bavaria who had been a staff artist at the Royal Botanical Garden in Munich. He had been making a name for himself in the United States as a botanical illustrator of great clarity, accuracy and minuteness of detail. Prestele produced four plates for the 1848 volume of the Transactions, and observers greeted his efforts with enthusiasm, celebrating them as far superior to Sharp’s chromolithographs.

Artists like Prestele did well in the commercial sector among nurserymen eager to advertise their fruit varieties, original or otherwise. But it was only the large firms that could afford to regularly publish catalogs with hand-colored plates.

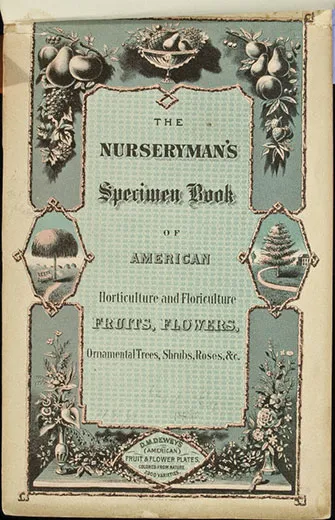

The smaller firms, which were legion, relied on peddler’s handbooks such as The Colored Fruit Book for the Use of Nurserymen, published in 1859 by Dellon Marcus Dewey, of Rochester, New York. It included 70 colored prints, which Dewey advertised had been meticulously drawn and colored from nature, saying their purpose was to “place before the purchaser of Fruit Trees, as faithful a representation of the Fruit as is possible to make, by the process adopted.” Deluxe editions of Dewey’s plate books, edged in gilt and bound in morocco leather, served as prizes at horticultural fairs and as parlor table books. Dewey produced the books in quantity by employing some 30 people, including several capable German, English and American artists. He also published the Tree Agents’ Private Guide, which advised salesmen to impress customers that they were God-fearing, upright and moral.

Still, colored illustrations could not by themselves protect an innovator’s intellectual property. Luther Burbank, the famed creator of fruits in Santa Rosa, California, fulminated that he had “been robbed and swindled out of my best work by name thieves, plant thieves and in various ways too well known to the originator.”

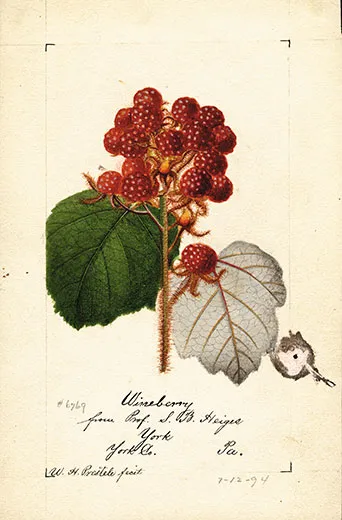

What to do? In 1891 some fruit men called for the creation of a national register of plants under the Department of Agriculture. The originator would send the department a sample, a description and perhaps an illustration of his innovation, and the department would issue a certificate, a type of trademark ensuring him inviolable rights in his creation. No such formal registration system was established, but a de facto version had been created in 1886, when the agency organized a division of pomology. It established a catalog of fruits and attempted to deal with the problem of nomenclature by hiring artists to paint watercolor illustrations of novel fruits received from around the country. The first such artist was William H. Prestele, one of Joseph Prestele’s sons. He produced paintings marked by naturalness and grace as well as by painstaking attention to botanical detail, usually including the interior of the fruit and its twigs and leaves.

By the late 1930s, when the illustration program ended, the division had employed or used some 65 artists, at least 22 of whom were women. They produced some 7,700 watercolors of diverse fruits, including apples, blackberries and raspberries, currants and gooseberries, pears, quince, citrus, peaches, plums and strawberries.

Yet neither the registration scheme nor any other method protected the fruit men’s rights as originators. Then, in 1930, after years of their lobbying, Congress passed the Plant Patent Act. The act authorized a patent to anyone who “has invented or discovered and asexually reproduced any distinct and new variety of plant.” It covered most fruit trees and vines as well as clonable flowers such as roses. It excluded tuber-propagated plants such as potatoes, probably to satisfy objections to patenting a staple of the American diet.

The act, the first statute anywhere that extended patent coverage to living organisms, laid the foundation for the extension, a half century later, of intellectual property protection to all organisms other than ourselves. But if it anticipated the future, the act also paid homage to the past by requiring would-be plant patentees, like other applicants, to submit drawings of their products. Law thus became a stimulus to art, closing the circle between colored illustrations of fruits and the intellectual property they embodied.

Daniel J. Kevles, a historian at Yale University, is writing a book about intellectual property and living things.