Hungarian Rhapsody

In a 70-year career that began in Budapest, André Kertész pioneered modern photography, as a new exhibition makes clear

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/indelible_tower.jpg)

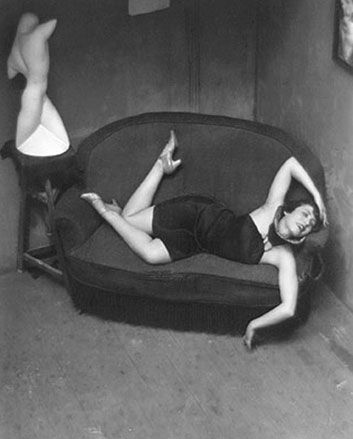

Several André Kertész photographs, including his witty picture of a dancer all akimbo on a sofa, are instantly recognizable. But a striking thing about his work, which is the subject of an exhibition at the National Gallery of Art, is that even the photographs you've never seen before look familiar.

Sunlit chairs casting nifty shadows on a sidewalk in (of course) Paris, commuters isolated on a train platform outside New York City, a woman wavily reflected in a carnival mirror—these and other Kertész photographs sort of disappoint at first. They seem like clever ideas that anyone with a camera and a passing knowledge of the craft's history would be tempted to try. But it turns out that he is the craft's history. His pictures seem familiar not because he borrowed others' tricks—rather, generations of photographers borrowed his. And still do.

"He was extremely influential," says Sarah Greenough, the National Gallery's curator of photographs and the organizer of the exhibition, the first major Kertész retrospective in 20 years. The territory that Kertész first explored, she says, is now "widely known and seen."

Kertész was born in Budapest in 1894, and by the time he died in New York City 91 years later, he'd been in and out of fashion a few times. He made his name in Paris in the 1920s, and the long American chapter of his life, beginning in 1936, would have been tragic if not for a comeback at the end. In his late 60s, he started making new photographs, reprinting old ones, publishing books and polishing his faded reputation. Now he's golden. In 1997, a picture he made in 1926—a less than 4 x 4-inch still life of a pipe and eyeglasses belonging to the Dutch painter Piet Mondrian—sold at auction for $376,500, among the highest prices ever paid for a photograph.

One of three children of his bookseller father and café—owner mother, Kertész had no particular aim until photography grabbed his interest as a teenager. In 1914, with World War I under way, he was drafted into the Austro-Hungarian Army; wounded in action in 1915, he recovered and traveled with the army through Eastern and Central Europe. The first image of his to receive recognition—he entered a Hungarian magazine's photo contest in 1916—was a portrait of himself picking lice from his uniform. He'd stumbled into a then-new way of documenting the world, that of the sensitive observer with an eye for, as he later put it, "little things."

Not that his ambition was small. After the war, he worked with one of his brothers photographing Budapest and the countryside before departing in 1925 to the center of the art universe. In Paris he flowered, capturing droll street scenes (a worker pulls a wagon with a statue in the seat), shooting the city at night and advising Brassaï, he of the Paris demimonde, how to do the same. He befriended Chagall and influenced the younger Henri Cartier-Bresson. "We all owe something to Kertész," Cartier-Bresson once said.

The dancer in his celebrated photograph was Magda Förstner, a Hungarian cabaret performer whom he ran into in Paris. He photographed her in 1926 in the studio of the Modernist artist István Beothy, whose sculpture stands near her. "She threw herself on the couch, and I took it at once," Kertész later recalled. (A review of published sources has turned up no word of what became of Förstner.) Satiric Dancer embodies the jazzy exuberance of Paris in the 1920s, or at least our romantic idea of it. Beyond that, says the photographer Sylvia Plachy, who is based in New York City and was a friend of Kertész’s, "it's an amazing composition. He caught that particular moment when everything is in perfect harmony."

Kertész had every reason to expect his rise would continue in New York. But he despised the commercial photography that he had crossed the Atlantic to do, and soon World War II stranded him and his wife, Elizabeth, in the States. The 15 or so years he spent photographing rich people's homes for House and Garden, he once said, made him consider suicide. From his apartment window he'd begun to take photographs of Washington Square Park, including elegant snowscapes. A solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in 1964 helped rescue him at age 70, reviving the American public's interest in his photographs and his own desire to work. (Elizabeth died in 1977.)

In 1984, about a year before he died, Kertész made a black-and-white photograph of interior doors reflected in a distorting mirror—a "mysterious and evocative image" that may have "represented his exit from the world," Robert Gurbo writes in the National Gallery exhibition catalog, André Kertész (co-authored by Greenough and Sarah Kennel). Far from copying other photographers, Plachy says, Kertész was "creative to the end."