The Iconic Hula Hoop Keeps on Rolling

How the loopy 60-year-old toy maintains its popularity

:focal(1216x705:1217x706)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/cf/c9/cfc903e9-4177-4821-8bfb-c375a007ddc8/julaug2018_a07_prologue.jpg)

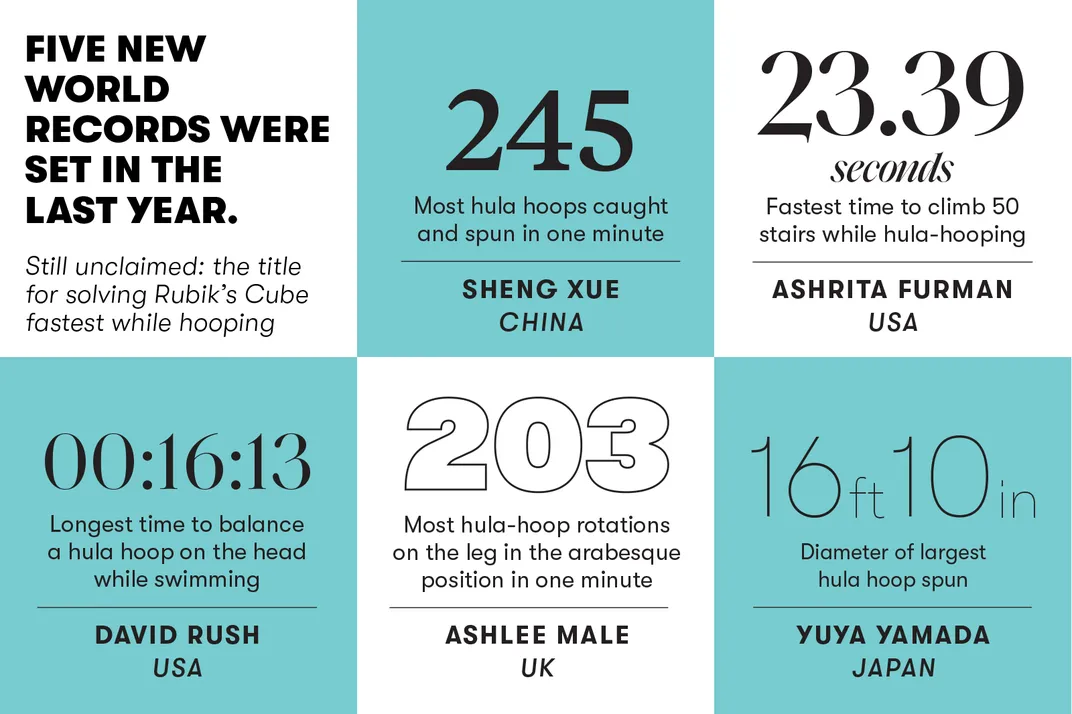

The women in the black-and-white videos wear Breton striped shirts, like those favored by Audrey Hepburn, and knee-high socks. Each has a hula hoop, or many of them. They swing them around their waists, but also around their wrists and elbows, shoulders and knees. A brunette in a bob rotates a hoop around her thighs, then does it while balancing on one leg before climbing the circle up her torso and into the air—a move called the “pizza toss.” This could be a scene from 1958, the year the United States went dizzy for hula hoops, except for the thousands of Instagram followers and the hashtags that accompany the videos: #hoop #tricks #skillz. The acrobats are Marawa’s Majorettes, a troupe of hyper hoopers led by Marawa Ibrahim. They’ve performed at the Olympics, set hooping world records and are among those credited with resurrecting the oh-so-’50s phenomenon for the age of social media.

The hula hoop was a fad that seemed destined to fade, like pet rocks, Beanie Babies and (one can hope) fidget spinners, but as it celebrates its 60th birthday, the plastic circle is trending.

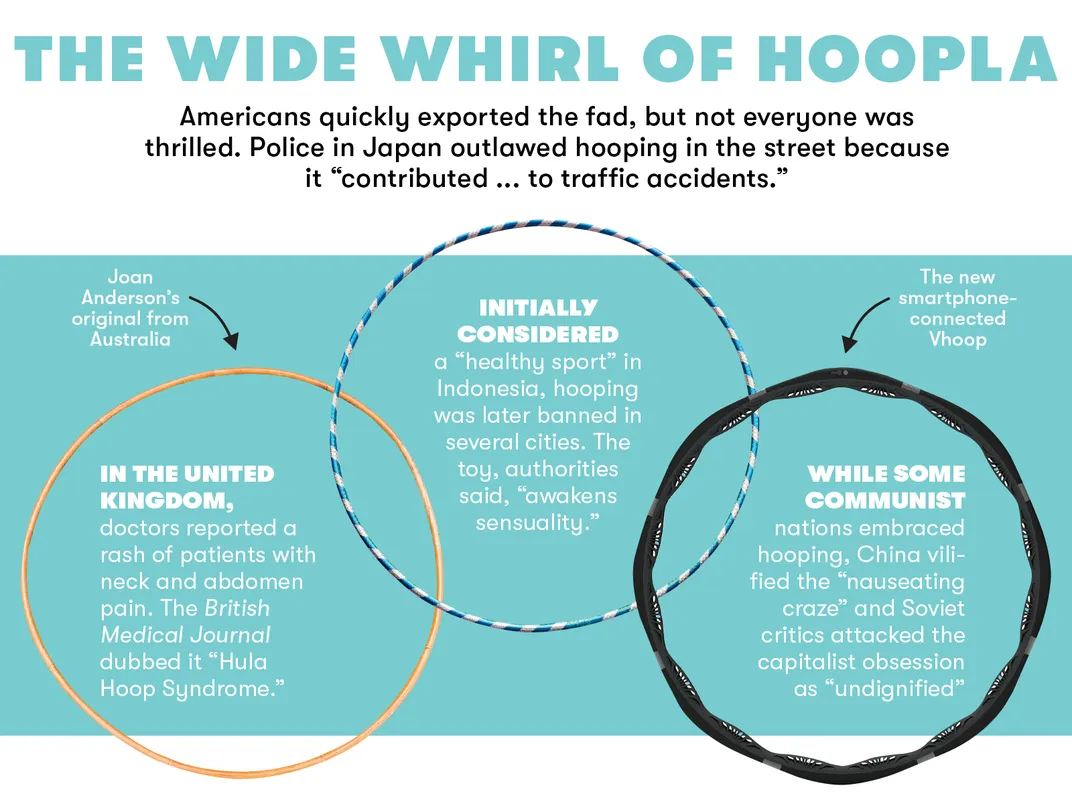

It was Richard Knerr and Arthur “Spud” Melin, founders of the Wham-O toy company, who transformed a popular Australian toy, the cane hoop, into a space-age craze. They made the ring out of lightweight and inexpensive plastic, trademarked a name that evoked the still-exotic Territory of Hawaii and its kinda sexy but still family-friendly hula dance and then launched a marketing campaign that was downright viral. The men took the hoops to Los Angeles parks, demonstrated the trick to kids and sent a hoop home with everyone who could keep it spinning. Company executives took the hoops on plane trips, hoping fellow passengers would ask about the odd carry-ons. And Wham-O tapped the powerful new medium of television with hokey, seemingly homemade advertisements. The word spread. The company sold more than 20 million hula hoops in six months.

Sales never again reached those heights, yet the plastic child’s toy has evolved over the years into art, exercise, even a form of meditation. (The rhythm of hooping helps clear the mind, devotees say.) It has been adopted by both counterculture—it is a fixture at Burning Man—and digital culture. This summer, a company called Virfit introduced the Vhoop fitted with sensors and a Bluetooth transmitter to monitor a user’s every twist and turn via smartphone app, marrying the quintessential 1950s obsession to the latest fitness-tracking fad. The price got an update, too: Wham-O’s original hula hoop sold for $1.98; the Vhoop is a much more modern $119.

Hula Girl

At 94, Joan Anderson, the subject of the new documentary short Hula Girl, is finally getting her due for helping kick off the country’s hoop mania. -- Interview by April White

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/60/dc/60dc0a0d-a435-465a-91bf-84d7ad0d78d5/julaug2018_a11_prologue.jpg)

At 94, Joan Anderson, the subject of the new documentary short Hula Girl, is finally getting her due for helping kick off the country’s hoop mania six decades ago. She spoke with us from California.

When did you first spot the hoop? It was 1957. I was visiting my family in Sydney, Australia, and while I was at my sister’s house, I heard people in the back room laughing and carrying on. I said, “What’s this all about?” and my sister said, “It’s a new kind of toy called the hoop.” People all over were doing it. It looked like fun, but it was really hard. I couldn’t do it at first.

Did you bring one home to Los Angeles? It wasn’t possible to bring one on the plane, but I told my husband about it. He had dabbled in the toy business and thought it might be something he’d be interested in producing, so I wrote to my mother and asked her to send me one. The man who delivered it to the door said, “Who would have something like this delivered all the way from Australia?” I’ve often wondered if he put it together that it was the first hula hoop.

What did your American friends think of this wacky Australian fad? We had the hoop at our house for months. The kids played with it and we showed it to our friends. One night one of them said, “You know, you look like you’re doing the hula.” I said, “There’s the name: hula hoop!”

You showed the hoop to the founders of the Wham-O toy company. Spud Melin interviewed us in the parking lot of the Wham-O plant in San Gabriel Valley, and I showed him how to use it. He said, “Is there anything else you can do with it?” He took it and kind of rolled it to see if it would come back to him. “It’s got possibilities,” he said. The next thing we knew, Spud called from a show at the Pan-Pacific in Los Angeles: “It’s crazy around the booth. Everyone is trying it. It’s really gone wild!”

Did you make a business deal? It was a gentleman’s handshake. “If it makes money for us, it’ll make money for you,” Spud said. “We’ll take care of it.” Well, they didn’t do a very good job. We were involved in a lawsuit with Wham-O. In the end they said they lost money, because the sales died suddenly.

Today, no one knows about your part in creating the hula-hoop craze. In the beginning, everyone knew. Then I think they began to wonder if that was true or not, because we didn’t get any recognition for it. Wham-O was the one that made the hula hoop big, but we brought it to the United States. I’m thrilled that the story—and the movie—is out there now.