In the Freezing Cold of Siberia, One Photographer Sought to Mix Oil and Water

In his latest project, British photographer Alexander James captures crude oil encased in frozen blocks of river water

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8e/e0/8ee0f52a-fd84-4c94-9e3f-0087bc42c4e6/galaxy.jpg)

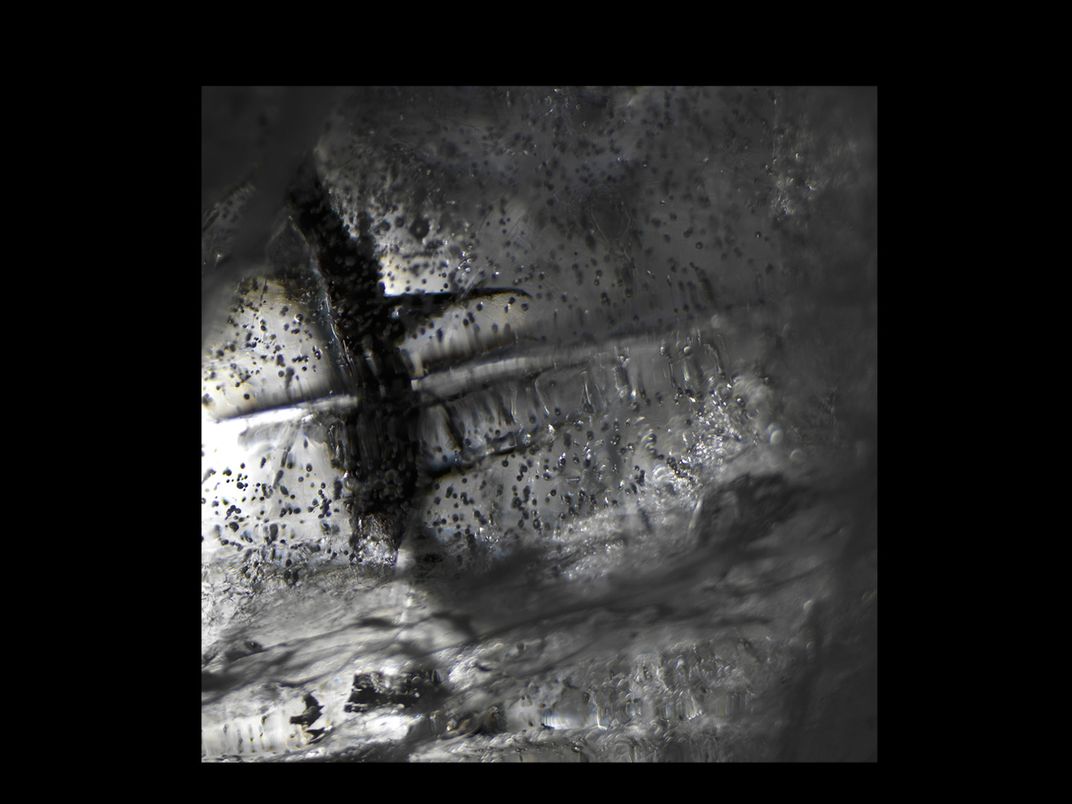

Alexander James still can’t feel his fingers. It’s only been a little over a week since the photographer returned from his six-week, Rocky Balboa-esque isolation in Siberia. There he was working on his most recent fine art project, “Oil and Water,” in which he combined the two elements famous for their inability to blend, entombing crude oil inside frozen blocks of river water and then photographing the results.

Siberia’s vast stretches of Arctic white were visually alien to Alexander James, a man whose usual aesthetic is black. The British photographer is best known for his photographs that echo the still life paintings of 17th century Dutch masters. In James’ previous series, he immersed fruit and foliage, butterflies and even gracefully posed figures in watery tanks of darkness.

Traveling by airplane, car, snowmobile and quad-runner, James made his way out to a lonely boathouse on the cold Yenisei River, near the town of Krasnoyarsk in Siberia. “It’s dragged out onto the river every winter so fishermen can use it as a lodge,” says James. “You’re not supposed to be living in it at all.” But the rugged location was the perfect place for him to work, and the ever-resourceful James finagled access using the local currency–a few cases of vodka. Food choices at the boathouse were slim. “Bread and fish for a month!” he laments.

Creation was an intensely physical process. James would spend up to ten hours a day outside in the wind and cold, cutting fresh ice lumps out of the frozen river crust and then dragging them up to 300 yards where he could begin work on them. “My thermometer stopped at -50 degrees Celsius,” James says. “It was off the clock for two weeks.”

James constructed forms out of wood and plastic to shape the ice. Once blocks of ice were brought inside, they were allowed to melt on plastic sheeting that covered the floor. “It probably would have looked like Al Capone’s back bedroom,” James recalls. The pure river water was then refrozen in desired shapes.

Importantly, oil for the project was locally sourced. A gentleman who lived nearby happened to have his own “nodding donkey,” and James procured a couple of barrels from him. Left sealed in a can, oil never freezes–it just becomes thick, like molasses. James chiseled various shapes, from smears to eggs, into the ice and, wearing fingerless gloves, pressed the oil into the hollowed spaces. “It was literally like black pizza dough in your hand,” James laughs. “I smelled like a bloody mechanic.”

Much trial and error was involved when combining and freezing the ice and oil, since there was no established process. James ended up destroying a number of his earliest ice block creations. “You could have used them as some sort of glamorous ashtray!” he chuckles. “They were the trial canvases.” But after week three, the process started to get smoother.

“None of the alchemy works without being a bit clever and tricky about the way you freeze things,” James explains. Oil was placed in the ice "cube" forms, and cubes were gradually built up, layer-by-layer of water, with multiple freezes and then shaped with a hammer and a chisel. Some of the largest works would receive up to 20 freezes, depending on how James wanted it to look. He learned how to manipulate the shape of the encased oil. James could cause fizzing within the ice by freezing a thin layer on top of a heavy oil base. Slow freezing resulted in gas pockets and trails in the ice, created from the release of heat and pressure in the oil. The abstract oil-filled ice “cubes” were generally one cubic meter (35 cubic feet) in size, with the largest weighing up to 200 kilograms (440 pounds).

Once the cubes were completed, James photographed his works, using 6x6 film, with no sort of digital manipulation on his final results. At the end of his stay, James took his ice blocks for “a parting ride,” on his quad-runner, leaving them each in places where he “thought they’d be comfortable,” bringing only photographs with him back to London. “There are things now morphing with the forest as we speak,” James says. “They’ll be there for months, and they’ll be changing daily.”

Though James didn’t interact with many Russians during his stay there, he felt like those he did meet respected and understood the intense dedication of his craft. While his last series was figurative and biblical, “Oil and Water” is different, abstract and very metaphorical of the dialogue between different cultures.

“I’m trying to create something beautiful that allows someone to find things they’ve never connected with for a long time,” says James. “Isn’t that what art does?”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jeff-Campagna-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jeff-Campagna-240.jpg)