The Inside Story of the Beatles’ Messy Breakup

Tensions leading to the split, announced 50 years ago today, had been bubbling under the band’s cheery surface for years

:focal(1527x864:1528x865)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/58/6d/586d1033-30bb-4f2b-b1d1-6dc8117c1290/gettyimages-3297187.jpg)

Fifty years ago, when Paul McCartney announced he had left the Beatles, the news dashed the hopes of millions of fans, while fueling false reunion rumors that persisted well into the new decade.

In a press release, on April 10, 1970, for his first solo album, “McCartney,” he leaked his intention to leave. In doing so, he shocked his three bandmates.

The Beatles had symbolized the great communal spirit of the era. How could they possibly come apart?

Few at the time were aware of the underlying fissures. The power struggles in the group had been mounting at least since their manager, Brian Epstein, died in August of 1967.

‘Paul Quits the Beatles’

Was McCartney’s “announcement” official? His album appeared on April 17, and its press packet included a mock interview. In it, McCartney is asked, “Are you planning a new album or single with the Beatles?”

His response? “No.”

But he didn’t say whether the separation might prove permanent. The Daily Mirror nonetheless framed its headline conclusively: “Paul Quits the Beatles.”

The others worried this could hurt sales and sent Ringo as a peacemaker to McCartney’s London home to talk him down from releasing his solo album ahead of the band’s “Let It Be” album and film, which were slated to come out in May. Without any press present, McCartney shouted Ringo off his front stoop.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/80/9a/809a27f0-09e9-49c1-adf7-cc6771678fa0/gettyimages-85234794.jpg)

Lennon had kept quiet

Lennon, who had been active outside the band for months, felt particularly betrayed.

The previous September, soon after the band released “Abbey Road,” he had asked his bandmates for a “divorce.” But the others convinced him not to go public to prevent disrupting some delicate contract negotiations.

Still, Lennon’s departure seemed imminent: He had played the Toronto Rock ‘n’ Roll Festival with his Plastic Ono Band in September 1969, and on Feb. 11, 1970, he performed a new solo track, “Instant Karma” on the popular British TV show “Top of the Pops.” Yoko Ono sat behind him, knitting while blindfolded by a sanitary napkin.

In fact, Lennon behaved more and more like a solo artist, until McCartney countered with his own eponymous album. He wanted Apple to release this solo debut alongside the group’s new album, “Let It Be,” to dramatize the split.

By beating Lennon to the announcement, McCartney controlled the story and its timing, and undercut the other three’s interest in keeping it under wraps as new product hit stores.

Ray Connolly, a reporter at the Daily Mail, knew Lennon well enough to ring him up for comment. When I interviewed Connolly in 2008, he told me about their conversation.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b7/33/b733c041-f59c-4f19-abbc-2aa4d2ef4e7c/gettyimages-91139147.jpg)

Lennon was dumbfounded and enraged by the news. He had let Connolly in on his secret about leaving the band at his Montreal Bed-In in December, 1969, but asked him to keep it quite. Now he lambasted Connolly for not leaking it sooner.

“Why didn’t you write it when I told you in Canada at Christmas!” he exclaimed to Connolly, who reminded him that the conversation had been off the record. “You’re the f–king journalist, Connolly, not me,” snorted Lennon.

“We were all hurt [McCartney] didn’t tell us what he was going to do,” Lennon later told Rolling Stone. “Jesus Christ! He gets all the credit for it! I was a fool not to do what Paul did, which was use it to sell a record…”

It all falls apart

This public fracas had been bubbling under the band’s cheery surface for years. Timing and sales concealed deeper arguments about creative control and the return to live touring.

In January 1969, the group had started a roots project tentatively titled “Get Back.” It was supposed to be a back-to-the-basics recording without the artifice of studio trickery. But the whole venture was shelved as a new recording, “Abbey Road,” took shape.

When “Get Back” was eventually revived, Lennon—behind McCartney’s back—brought in American producer Phil Spector, best known for girl group hits like “Be My Baby,” to salvage the project. But this album was supposed to be band only—not embroidered with added strings and voices—and McCartney fumed when Spector added a female choir to his song “The Long and Winding Road.”

“Get Back”—which was renamed “Let it Be”—nonetheless moved forward. Spector mixed the album, and a cut of the feature film was readied for summer.

McCartney’s announcement and release of his solo album effectively short-circuited the plan. By announcing the breakup, he launched his solo career in advance of “Let It Be,” and nobody knew how it might disrupt the official Beatles’ project.

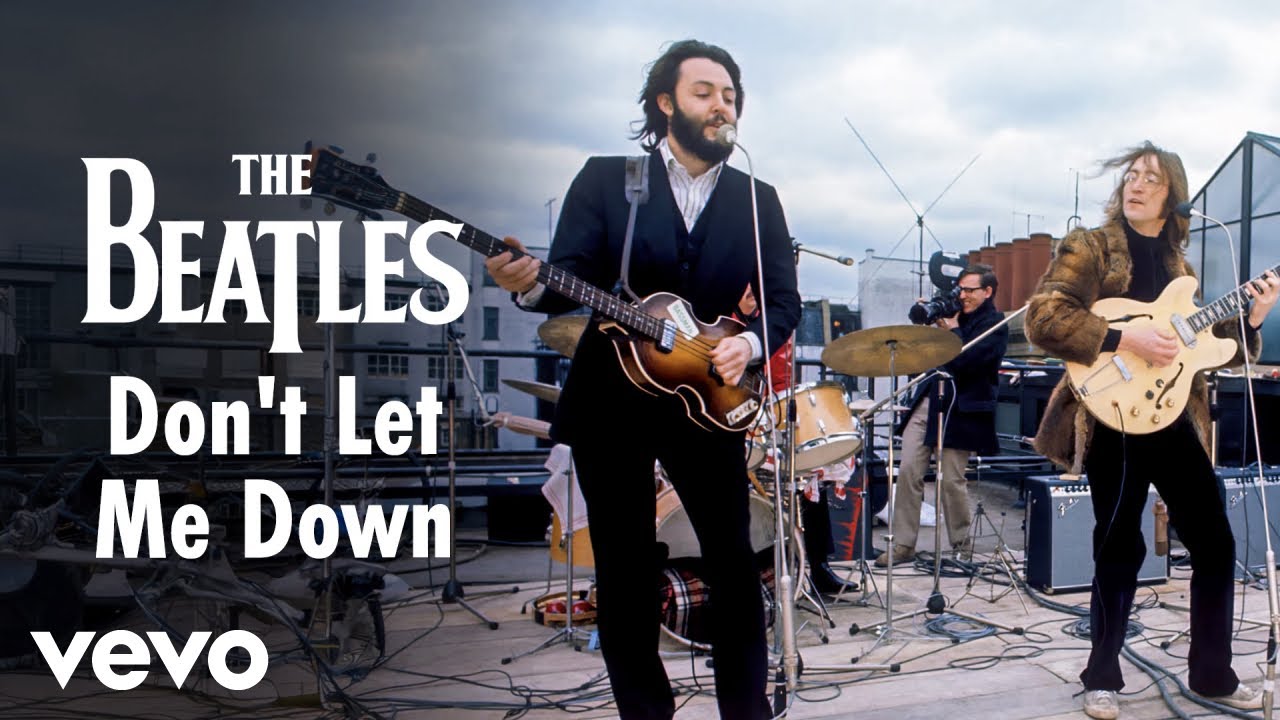

Throughout remainder of 1970, fans watched in disbelief as the “Let It Be” movie portrayed the hallowed Beatles circling musical doldrums, bickering about arrangements and killing time running through oldies. The film finished with an ironic triumph—the famous live set on the roof of their Apple headquarters during which the band played “Get Back,” “Don’t Let Me Down,” and a joyous “One After 909.”

The album, released on May 8, performed well and spawned two hit singles—the title track and “The Long and Winding Road”—but the group never recorded together again.

Their fans hoped against hope that four solo Beatles might someday find their way back to the thrills that had enchanted audiences for seven years. These rumors seemed most promising when McCartney joined Lennon for a Los Angeles recording session in 1974 with Stevie Wonder. But while they all played on one another’s solo efforts, the four never played a session together again.

At the beginning of 1970, autumn’s “Come Together”/“Something” single from “Abbey Road” still floated in the Billboard top 20; the “Let It Be” album and film helped extend fervor beyond what the papers reported. For a long time, the myth of the band endured on radio playlists and across several Greatest Hits compilations, but when John Lennon sang “The Dream is over…” at the end of his own 1970 solo debut, “John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band,” few grasped the lyrics’ implacable truth.

Fans and critics chased every sliver of hope for the “next” Beatles, but few came close recreating the band’s magic. There were prospects—first bands like Three Dog Night, the Flaming Groovies, Big Star and the Raspberries; later, Cheap Trick, the Romantics and the Knack—but these groups only aimed at the same heights the Beatles had conquered, and none sported the range, songwriting ability or ineffable chemistry of the Liverpool quartet.

We’ve been living in the world without Beatles ever since.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Tim Riley is an associate professor and graduate program director for journalism at Emerson College.