The Inside Story of Christo’s Floating Piers

The renowned artist dazzles the world again, this time using a lake in northern Italy as his canvas

Christo Invites Public to Walk on Water

—headline, The Art Newspaper, April 2015

“I thought, ‘I’m going to be 80 years old. I’d like to do something very hard.’”

—Christo

**********

The lake is impossible.

The lake is a painting of a lake; the water a painting of water. Like floating on a second sky. Too blue. Too cool. Too deep. Impossible. The mountains, too. Too steep, too green with trees, too white with snow. Villages pour down the hills and run russet and ocher and brown to the water’s edge. Red tile rooftops necklace the shore. Flat calm, and at midday the quiet carries from one end of Lago d’Iseo to the other, from the vineyards to the mines to the small hotels. The stillness here has weight. He raises his voice.

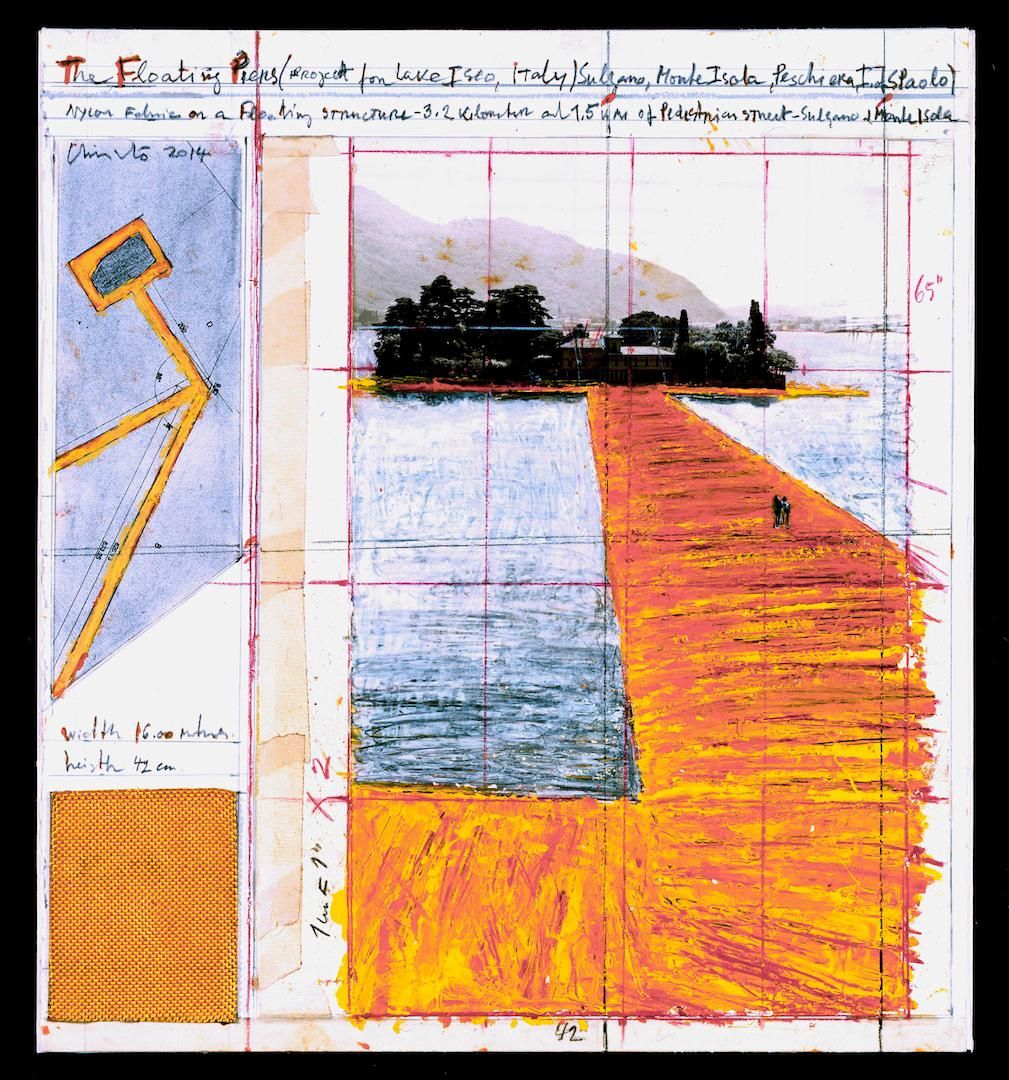

“Floating Piers will be three kilometers long. And will use 220,000 polyethylene cubes. Fifty centimeters by 50 centimeters. Two hundred twenty thousand screws. Interlocking.”

KiloMAYters. CentiMAYters. His English is good, but the Bulgarian accent is thick. Even now, so many years later. He tilts his chin up to be heard.

“Ninety thousand square meters of fabric.”

MAYters.

“Not just on the Piers, but in the streets also.”

The hair is a white halo beneath a red hard hat and above the red anorak. Dress shirt and jeans. Oversized brown boots. He is slender, big-eared and fine-boned, with long, expressive hands. Not tall but straight, unbent even at 80. He radiates energy and purpose.

**********

“From Sulzano to Monte Isola and out to Isola di San Paolo,” he says, pointing. “Each pier built in sections 100 meters long. Then joined.” Behind the glasses the eyes are dark, lively, tired. He smiles. This, the talking, is part of the art, too. “Sixteen meters wide, and slope into the water along the sides,” he gestures a shallow angle with his right hand, “like a beach.” Two dozen members of the Italian press and two dozen local politicians nod and stand and whisper.

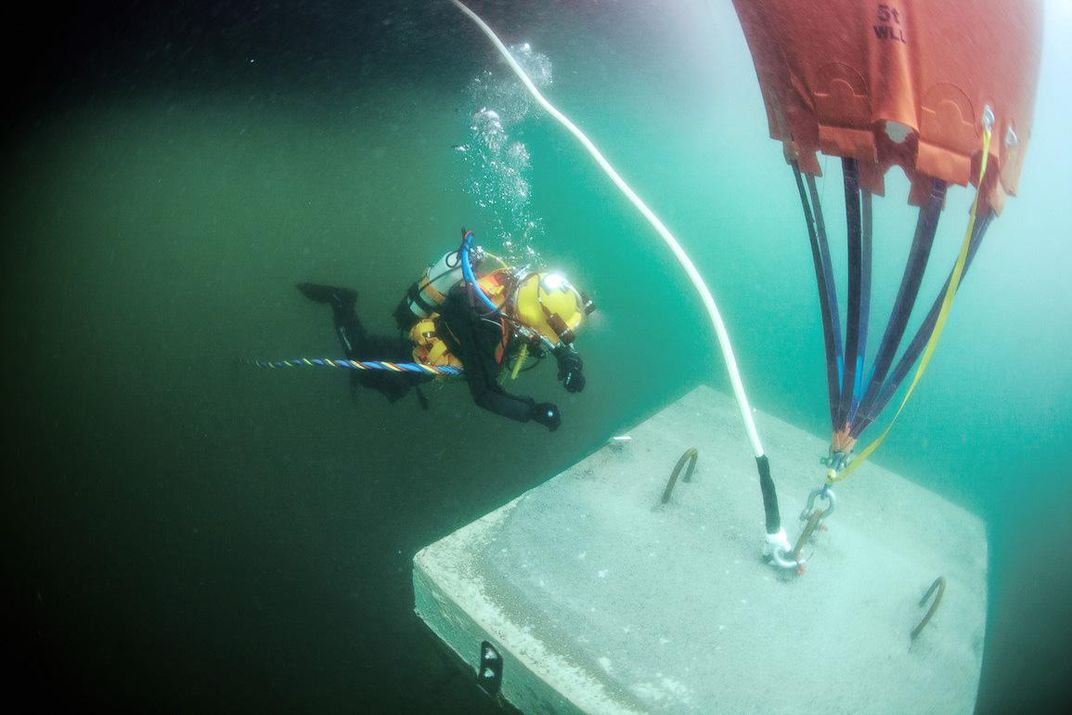

“One hundred sixty anchors. Each anchor weighs five tons,” Christo says.

He’s standing just aft of the deckhouse on the boat the divers use to sink those anchors. The boat is a long platform on long hulls. Like him, the boat and the divers are from Bulgaria. The divers have been out here most of the winter, working in the dark and the cold and the unimaginable silence of the deep lake. “One hundred meters depth,” says Christo. The boat is a few hundred yards offshore, near the floating corral where finished sections of pier are tied up. Waiting.

He moves from group to group —everyone gets a comment, everyone gets a quote, a photo—surrounded by reporters and local mayors.

“Thirty-five boats. Thirty Zodiacs. Thirty brand-new motors.”

Cameras. Microphones. Notebooks.

“Sixteen days. Hundreds of workers.”

The smile widens.

“This art is why I don’t take commissions. It is absolutely irrational.”

In the construction shed onshore, still more Bulgarians are back from lunch. Two teams screw together the Floating Piers block by block by block, eight hours a day, seven days a week. It will take months. You can hear the sound of the big impact wrench for miles in the quiet.

**********

Two weeks at a time, he is the most famous artist on earth.

Christo. Last name Javacheff. Born June 13, 1935, in Bulgaria. Studies art. Flees the Soviet advance across the Eastern bloc at 21, arrives in Paris spring, 1958. Meets his future wife and collaborator that year while painting her mother’s portrait. The first wave of fame comes when they block the rue Visconti in Paris with stacked oil drums. A sculptural commentary on the Berlin Wall and oil and Algeria and culture and politics. That was 1962.

“At a very early moment in postwar art, they expanded our understanding of what art could be,” says art historian Molly Donovan, an associate curator at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. “Crossing the boundary out of the gallery and the museum—by putting works in the public sphere, in the built environment—that was really groundbreaking in the early ’60s.”

Then small wraps and faux storefronts and draped fabrics and wrapped fountains and towers and galleries. Then 10,000 square feet of fabric wrapping the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago. Then in 1969 a million square feet of fabric draped and tied over the rocks outside Sydney and they are suddenly/not suddenly world famous. “The concept of art was so narrow at the time,” recalled Australian artist Imants Tillers, “that Wrapped Coast appeared to be the work of a madman.” Filmmakers start following them. Journalists. Critics. Fans. Detractors. Then the debate over what it is. Conceptual art? Land art? Performance art? Environmental art? Modernist? Post-Minimalist?

As critic Paul Goldberger has said, it is “at once a work of art, a cultural event, a political happening and an ambitious piece of business.”

Valley Curtain, Colorado, 1972. Two hundred thousand, two hundred square feet of fabric drawn across the canyon at Rifle Gap. Running Fence, California, 1976. A wall of fabric 18 feet high running 24.5 miles through the hills north of San Francisco into the sea; now in the collections of the Smithsonian Institution. Surrounded Islands, Miami, 1983. Eleven islands in Biscayne Bay surrounded by 6.5 million square feet of bright pink fabric. The Pont Neuf Wrapped, Paris, 1985. The oldest bridge in the city wrapped in 450,000 square feet of fabric, tied with eight miles of rope. The Umbrellas, Japan and California, 1991. Three thousand one hundred umbrellas, 20 feet high, 28 feet wide; blue in Ibaraki Prefecture, yellow along the I-5 north of Los Angeles. Cost? $26 million. Two accidental deaths. Wrapped Reichstag, Berlin, 1995. One million square feet of silver fabric; nearly ten miles of blue rope; five million visitors in two weeks. The Gates, New York City, 2005.

“They cross boundaries in our imagination about what’s possible,” Donovan says. “People like the sense of joyousness that they celebrate, the joy in the work. The work isn’t whimsical, necessarily. They’re serious works. The openness and exuberant colors—people respond to that.”

“Their projects continue to work on your mind,” she says. “Why do they feel so powerful or meaningful? On the global scale, they’ve elicited a lot of thought about what art can be, where it can be, what it can look like. They’ve really broadened the locations for where art can happen.”

So in 2005 when 7,503 gates open along 23 miles of paths in Central Park, attracting more than four million visitors, columnist Robert Fulford wrote in Canada’s National Post, “The Gates came and went quickly, like an eclipse of the sun. In their evanescence they recalled the Japanese cult of the cherry blossom, which blooms briefly each spring and in Japanese poetry symbolizes the brevity of life.”

“I think the really amazing thing about Christo, the reason why he has found the sweet spot between the art world and the world at large—and is such a popular public figure,” Michael Kimmelman of the New York Times says, “is because he realized that if he took art, if he used the political process and public space as the place in which to make art, and to bring the public into the process itself, that he would redefine both the audience for this art and also redefine what had been called public art before.”

**********

Halfway between Bergamo and Brescia; halfway from Milan to Verona on the road to Venice—Lago d’Iseo is the fourth-largest lake in Lombardy. It is a low-key summer resort with a history going back to antiquity. The mountains are veined with marble and iron and have been quarried and mined for more than 1,000 years. Franciacorta, Italy’s answer to Champagne, is made from the grapes grown on the lake’s southern shore. In the 1920s there was a famous seaplane factory near the little town of Pilzone. But the lake has never had the allure or the matinee idol star power of its more famous neighbor, Lake Como. Until now.

From June 18 to July 3, 2016, Christo will reimagine Italy’s Lake Iseo. The Floating Piers will consist of 70,000 square meters of shimmering yellow fabric, carried by a modular dock system of 220,000 high-density polyethylene cubes floating on the surface of the water. —christojeanneclaude.net

**********

It isn’t really yellow. Is it? More like saffron. Like The Gates in Central Park. Like Valley Curtain. That signature color of theirs. Orange, but not orange. Orange brightened by something like gold; tempered by something like red. Maybe. And it’ll be different at the edges where it’s wet. Darker. Like Jeanne-Claude’s hair.

Jeanne-Claude Denat de Guillebon. The general’s daughter. Organized. Tough. Funny. Argumentative. Charming. Beautiful. Christo Javacheff’s lover and wife and partner in art for more than 50 years. Famously born on the same day. Famously inseparable. She was the one out front, the one offering quotes.

“Our work is only for joy and beauty,” Jeanne-Claude would say, or “It is not a matter of patience, it is a matter of passion.”

She died in 2009. The name Christo belongs to them both. This is his first major project without her.

Maybe the best way to understand her, to understand them, is to go online and watch the film from her memorial at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

When she says “Artists do not retire. They die,” it knocks you back.

**********

Christo is sitting in the café of a lakefront hotel being interviewed by a writer from Elle magazine. He explains how the Floating Piers will connect the mainland to the island of Monte Isola for the first time ever. He talks about the beauty of the medieval tower on the island, the Martinengo, and the abbey at the summit, and he talks about tiny Isola di San Paolo, a Beretta family vacation home, and he tells her about the complex engineering and the ridiculous expense and what a bright, brief complication it will all be.

“Sixteen days, hundreds of workers, $15 million.”

He explains the financing—he pays for every project by selling his art, no donations, no sponsorships—and suggests she read the 2006 Harvard Business School case study to learn the details of how they do it.

In the months and years leading up to every installation, he produces hundreds of smaller pieces of art: preparatory sketches, studies, models, paintings, collages. This he does alone. Today the New York studio is filled with scores of canvases in every size and shade of blue; lakes and piers in every medium from pen to pencil to pastel, crayon to paint to charcoal; islands and towers and abbeys mapped as if by satellite, or sketched in a few quick strokes; simple as a color block, or complex and precise as an architectural elevation. Some of the multipanel pieces are several meters wide by a meter or more high and sell for hundreds of thousands of dollars to a loyal circle of collectors.

No more will be produced once The Floating Piers has come and gone.

**********

At the shed a few hundred meters up the shore, the Floating Piers team works out of a converted shipping container. The little room is immaculate. Lined with tables and shelves and lockers and computers, stacked with equipment and documents, buzzing with purpose. Three people on three phones having three conversations in three languages. The espresso machine hisses and pops.

There’s Wolfgang Volz, project manager. He’s the smart, charming, compact German who’s worked on every Christo and Jeanne-Claude project since 1971. Vladimir Yavachev, operations manager, Christo’s nephew—tall, dark, funny. Diver and cinematographer, he started his career with Xto and JC more than 20 years ago—by carrying Wolfgang’s camera bag. His wife and daughter, Izabella and Mina, are here as well. Working. Frank Seltenheim, assembly manager—who got his start as one of the climbers draping fabric over the Reichstag. Antonio Ferrera, documentarian, who records every waking moment of every project. Marcella Maria Ferrari, “Marci,” new chief administrator. “She’s already one of us,” says Wolfgang, who is also simultaneously on the phone with New York. New York in this case being Jonathan Henery, Jeanne-Claude’s nephew and the vice president for all the projects. Slim, mid-40s, he worked shoulder to shoulder with her for 20 years and does now what she did. Organize. Catalog. Energize. Mediate.

**********

The office in New York is an old cast-iron building in SoHo. Christo and Jeanne-Claude moved there from Paris in 1964, bought the building from their landlord in the early 1970s and never left. The reception room smells of flowers and honey and patchouli, and there’s always music playing low somewhere. And if you go to visit Christo, he’ll come down from the studio to greet you, his French cuffs tied with string and covered in charcoal dust, and talk to you about anything. About the old days downtown with Warhol and Jasper and the guys.

“Oh sure,” he says, “yes, Andy and Rauschenberg, Johns, in that time, we were all trying to make our work visible.”

About what’s next.

“We’re waiting now for the federal appeals to tell us about Over the River [a long-planned fabric installation on the Arkansas River in Colorado]. It could happen any moment.”

About Jeanne-Claude.

“I miss most the arguments about the work.”

And he is not only polite, he is warm and affectionate and engaged, and he never says it, he’s too well-mannered, but he wants to get back to work. As soon as you go, as soon as you shake hands and head for the door, he’s on his way back upstairs to the studio.

**********

Catastrophe.

In front of all those reporters, Christo said the ropes for the project come from the USA.

“They come from Cavalieri Corderia,” Vlad says. “Up the road in Sale Marasino! Five kilometers from here! Where you’re speaking tonight!”

“Oyoyoy,” says Christo, his comic incantation of surprise or confusion or self-mockery.

“You have to say first thing that the ropes for Floating Piers come from Cavalieri Corderia of Sale Marasino.” Vladimir is emphatic.

This is important. Every project uses as many local vendors and fabricators as possible. Nearly a quarter of a million floating cubes are being blow-molded around the clock in four factories in northern Italy, for example. Goodwill and good business.

“Oyoyoy. Cavalieri Corderia of Sale Marasino.”

You’ll hear him whispering it the rest of the day.

The presentation at the community center in Sale Marasino is the same one he gave two weeks ago at a high school in New York City, but the simultaneous translation slows it down a little. Wrapped Coast. Valley Curtain. Running Fence. Surrounded Islands. Pont Neuf. Reichstag. The Gates.

That Christo speaks in run-on sentences powered by his enthusiasm makes a translator’s job harder; she delivers the Italian version prestissimo—but can never quite catch up.

First thing he says: “I want to thank the ropemakers of Cavalieri Corderia for all the rope we’re using. Excellent.” The room erupts in a round of applause.

The small theater is full, maybe 300 people. This is one of the last stops on the charm campaign. They’ve done this show in almost every village around the lake. The audience sees all the projects PowerPointed—from Wrapped Coast to The Gates in a series of photos, a greatest hits flyover, then a few sketches of The Floating Piers’ 220,000 cubes. 70,000 square meters of fabric. 160 anchors. Five tons, etc. And so forth.

He’s out front now, where she used to be.

“The art is not just the pier or the color or the fabric, but is the lake and the mountains. The whole landscape is the work of art. It’s all about you having a personal relationship with it. You in it, experiencing it. Feeling it. I want you to walk across it barefoot. Very sexy.”

Translation. Applause. Then the audience Q and A.

“How much will it cost?” is almost always the first question.

“Nothing. It is free. We pay for everything.”

“How do we get tickets?”

“You don’t need tickets.”

“What time does it close?

“It will be open around-the-clock. Weather permitting.”

“What happens when it’s over?”

“We recycle everything.”

“How do you stay so energetic?”

“I eat for breakfast every day a whole head of garlic, and yogurt.”

And Christo always answers two last questions, even when no one asks them.

What is it for? What does it do?

“It does nothing. It is useless.”

And he beams.

**********

Now photographs and autographs with anyone who wants one. Then the mayor takes him up the hill to dinner.

A lovely rustic inn high among the trees. Orazio. In the main dining room, in honor of Christo, an arrangement of every local dish and delicacy. Table after table of antipasti and meat and fish and bread and wine and vinegar from the fields and farms and streams around the lake. A nervous young man rises and makes an earnest speech about the unparalleled quality of the organic local olive oil. When he finishes, two cooks carry in a whole roast suckling pig.

At a table in back Christo picks at a small plate of pickled vegetables and roast pork and bread and olive oil while encouraging everyone else to eat up. “Sometimes we have to remind him to eat at all,” says Vladimir. Wolfgang is on and off the phone about the upcoming meeting in Brescia with the prefetto, the prefect, a kind of regional governor. Very powerful.

After dinner, two things. First, someone presents him with a “wrapped” bicycle. It is oddly reminiscent of his earliest work; that is, there’s a wrapped motorcycle of his from the early 1960s in a collection somewhere worth millions. He’s very gracious about the bike.

Then local author Sandro Albini takes Christo’s elbow and spends several minutes explaining his theory that the background of the painting La Gioconda (the Mona Lisa) is actually Lago d’Iseo. He makes a convincing case. Leonardo visited here. The timing works. Mr. Albini is a quiet sort, but determined, and the talk goes on awhile.

Giving you the chance to think of Leonardo and art and Christo and how artists work into late life and what that might mean. Some artists simplify as they grow old, the line becoming gestural, the brush stroke schematic; some complicate, and the work becomes baroque, rococo, finding or hiding something in a series of elaborations. Some plagiarize themselves. Some give up.

Matisse, Picasso, Monet, Garcia-Márquez, Bellow, Casals. There’s no one way to do it. Maybe it’s the desire for a perfection of simplicity. “The two urges, for simplicity and experiment, can pull you in opposite directions,” says Simon Schama, the art historian. He situates Christo and his projects in a long tradition, a continuum extending from Titian to Rembrandt to Miró to de Kooning. “The essence of it is simple, but the process by which it is established is a great complication.” That’s the tension of late life essentialism. The elemental language of Hemingway in The Old Man and the Sea. Late Mozart, the Requiem. Beethoven, the chilling clarity of the late String Quartets. (So modern they could have been written last week.) Think of Shakespeare, the late plays. The Tempest. Or the Donald Justice poem, “Last Days of Prospero,” part of which reads:

(What tempests he had caused, what lightnings

Loosed in the rigging of the world!)

If now it was all to do again,

Nothing was lacking to his purpose.

The idea for the piers is more than 40 years old. Christo and Jeanne-Claude got the notion from a friend in Argentina who suggested they make an environmental piece for the River Plate. Couldn’t be done. Then they tried Tokyo Bay, but the bureaucracy was impossible and the technology wasn’t there. Hence the thought:

“I’m going to be 80 years old. I’d like to do something very hard.”

The old man is heir to the young man’s dream. The old man honors a promise. Artists do not retire.

Christo thanks Mr. Albini and heads for the car.

Now back to the shed.

Now to work.

Then to sleep.

**********

Now a field trip. To the top of the hill behind the factory. The owners know someone who knows someone who owns an estate on the ridgeline a thousand feet up from the shed. Nine people in a Land Rover Defender on a road like a goat trail drive to the top of the mountain.

It’s a stately old place gated and terraced with low walls and gardens and olive trees. The view from every corner is the whole dome of heaven, a world of Alps and lake and sky.

Christo stands alone at the edge of the garden for a long time. Looks down to the water. Looks down to the sheds. Picturing in the world what he’s already made in his mind. From here he can see it complete.

“Beautiful,” he says to no one in particular.

Vlad, less moved in the moment by beauty than by opportunity, points at a high peak a few kilometers east and says, “We can put the repeater over there.” They’ll have their own radio communications network for The Floating Piers. Operations, security, personnel, logistics.

Then Vlad and Wolfi and Antonio are arranging a portrait-sitting for Marci on one of those low walls, using a smartphone to see if the background matches that of the Mona Lisa—as was explained to them all at such great length. Marci’s smile is indeed enigmatic, but the results are inconclusive.

So. La Gioconda. Think of how it makes you feel. Think of The Gates. Running Fence. The Umbrellas. Wrapped Reichstag. Surrounded Islands. Think of the power of art. The Gates didn’t change Central Park. The Gates didn’t change Manhattan. The Gates changed you. Years later you still think of them.

We reserve for art the same power we grant religion. To transform. Transcend. To comfort. Uplift. Inspire. To create in ourselves a state like grace.

**********

Now Brescia, and the prefect.

Same presentation, but in a high marble hall to a modest audience of local swells. The prefetto, square-jawed, handsome, humorless in a perfectly tailored blue suit, leads off. Then Christo.

“What I make is useless. Absurd,” and so forth, through the years and the projects. He spends a few minutes on two future possibilities. Over the River, and The Mastaba, a massive architectural undertaking, permanent this time, an Old Kingdom tomb hundreds of feet high built of oil drums in the deserts of Abu Dhabi.

When Christo speaks at these things, you get the sense—infrequently but powerfully—that he’s waiting for Jeanne-Claude to finish his sentence.

After the PowerPoint the power, and a party for the local gentry in the prefetto’s official suite of rooms.

Fancy appetizers, tiny and ambitious, to be eaten standing. Franciacorta in flutes. An entire tabletop of fresh panettone.

For the next hour Christo stands in place as a stream of local dignitaries present themselves. He shakes hands and leans in to listen to each of them. Antonio floats by with his camera. They’ll ask all the same questions. When? How much? What next?

There’s always a little space in the circle for her.

If you watch him closely enough you can see it. Or maybe you just think you see it. Want to see it. There’s a space to his left. And that thing he does with his left hand when he’s talking to the politicians and the bureaucrats. How the fingers flex and the thumb brushes the fingertips, like he’s reaching for her hand.

**********

Now west out of Brescia on the autostrada. Christo, Wolfgang, Antonio. Fast. 140, 150, 160 kilometers per hour—the big Mercedes a locomotive in the dark.

Wolfgang driving. Christo deep in the back seat behind him. Antonio up front riding shotgun with the camera in his lap. “I thought that went well,” he says. “They were very nice. They really rolled out the red carpet for us.”

“They did,” says Wolfgang.

Christo is quiet for the first time since morning, looking out the window into Hour 15 of a 20-hour day. Italy is a blur.

“Still...”

“I think they really like us...really like the project.”

“Still,” Wolfgang says, “I’d wish for a little less red carpet and a little more action.”

Absently, looking out his window, Christo nods.

“You saw that conference room,” Wolfgang says to Antonio. “We’ve spent a lot of time in that conference room. Hours. Hours and hours.”

“On the permissions?”

“Yes. We have all the permits and all the permissions. Now. But it took a lot of meetings around that table. Month after month. Me and Vlad back and forth. Christo. Back and forth. They are very, um, deliberate.”

**********

And this is part of the art, too, the private meetings and the public hearings and the proposals and counter proposals and the local politicians nodding and smiling. The photo-ops.

“What about the traffic plan?” Christo asks. “Could you tell did he read the traffic plan?”

“I don’t know,” Wolfgang says. “I don’t think so.”

“Oyoyoy,” Christo says low from the far corner of the car.

The traffic plan for The Floating Piers is 175 pages long. It took a year to prepare. It cost €100,000.

“Maybe he’s read it,” Wolfgang says, his hands motionless on the wheel. “Maybe he hasn’t. He’s inscrutable.”

Floating Piers will draw perhaps 500,000 visitors in 16 days to a town with one main road.

“Oyoyoy.”

“Yes. Indeed. Oyoyoy.”

“When will they read it?”

“Who knows? They are in no hurry.”

“We are,” says Christo.

“Always,” says Wolfgang.

“It would be better to start sooner.”

“Undoubtedly.”

“And not leave this for the last minute. The buses. The police. The roads. The people. Oyoyoy. How could they not read it yet?”

“Maybe he read it. Maybe they all read it.”

“Why do they wait? What do they have to do? Nothing. Nothing. They just have to agree to it. Just have to say yes. They don’t even have to pay for anything. We pay for everything.”

Then everyone is quiet. Italy rushes past. The instrument panel glows.

“Still,” Antonio says, “they were very nice.”

**********

Maybe this is the life you’d choose for yourself if you could. Nights all over the world in strange, wonderful places. You and your family. Loved by everyone.

Now a restaurant in Palazzolo sull’Oglio, a small town a half-hour south of the lake.

“Bellissimo grande!” calls a woman on her way out the door as she sees Christo walking past her. Big beautiful.

Vlad found this place. A fourth-generation family cucina run by Maurizio and Grazia Rossi. Modest. Close to the train station. Dark wood. Frosted glass doors. A workingman’s place. On the bar is a Faema E 61 espresso machine as big and bright as the bumper of an antique Cadillac. The dining room in back is hung every which way with the work of local painters. It’s the kind of restaurant you’re nostalgic for even as you’re sitting in it.

“Relax,” Christo says. “Sit down. Eat.”

And they do. Frank the climber is here, and Izabella and Mina, and Antonio and Wolfi and Vlad, Marci and Christo, and the sweet, long-faced president of the lake association, Giuseppe Faccanoni. All at the big table up front. Simple menu. Large portions. Tripe soup. Passata di fagioli. White lasagna. Local fish. Local meat. Local wine. The owner’s uncle makes the cheese. Franciacorta from the slopes of Lago d’Iseo. “Salute!”

Conversations and sentence fragments around the table, overlapping dialogue like something out of Preston Sturges. For example, they moved out of a lakeside hotel into a chateau up in the hills.

“We’re saving €30,000 a month,” says Vladimir. “Mina, honey, what do you want?”

“There’s a billiard room,” Christo says.

“I don’t want the meatballs,” says Mina.

“But no one has used it yet,” says Wolfgang. “I’ll have the tripe. We’re all working seven days a week.”

“Grazie,” says Maurizio.

“Maybe the meatballs,” says Izabella.

Plates come and go, meatballs are eaten, wine poured. Eventually, briefly, the traffic plan comes around again.

“Oyoyoy.”

**********

Mina is asleep on Izabella’s lap. It’s late. Wolfi and Marci are going back and forth on their phones with the carabinieri. An alarm went off at the shed, but no one knows why. Wolfgang thinks the night watchman tripped it himself.

Dessert now, and Maurizio wants Christo to try the homemade halvah. “I know what my child likes and I know what Christo likes,” Vlad says to him. “He won’t like the halvah.”

He does not like the halvah.

So they bring him a big wedge of vanilla cake with fresh whipped cream. For the rest of the table the owner brings out cookies made by a cooperative of refugee women he sponsors from North Africa. Then espresso. Coming up on midnight.

Vlad takes most of the table home to the chateau. Wolfi drives back to the shed on the lake to work a few hours in the quiet, and to check the alarm.

**********

At dawn it’s silent around the lake. Nothing moves but the sun.

Somehow all this exists outside the punch-line postmodernism of kitsch and performance art, outside the smooth jazz standards of mid-century living room modernism, outside earnestness or irony or intention, outside category of any kind. Somehow the installations are as intimate as they are monumental, and no matter what else is happening, inside the work of art where you stand you’re safe.

The Floating Piers.

Maybe the real work of an artist’s life is the artist’s life.

**********

A month later he’s back in New York City. He works early. He works late. He’s upstairs in the studio, making the big pieces to pay for the piers. The French cuffs are dark with charcoal.

Vlad calls. Wolfi calls. Marci calls. Calls come all day every day with updates from Italy: more sections finished; more anchors sunk; bills in/checks out; trucks come/trucks go; tourists block traffic to catch a glimpse of the shed; of the piers; of Christo. The prefetto needs more paperwork. The days are tick-ticking away.

If you were to visit him, you’d meet him in that second-floor reception area. Reporters step in/reporters step out. Christo’s tired, but his eyes are bright and the handshake’s firm.

You’d smell that perfume and hear that music, and by now you’d know the perfume was Jeanne-Claude’s. Angel, by Thierry Mugler. Christo sprays it every day, upstairs and down. And the music is the Mozart she loved, the Piano Concerto No. 27, Mozart’s last, and he plays it on a loop, low, as the magic to conjure and keep her.

Then another dinner downtown.

“Three kilometers,” Christo says. “Two hundred twenty thousand polyethylene cubes. The Rolls-Royce of cubes. Ninety thousand square meters of fabric on the piers and in the streets.”

MAYters.

He’s building the piers out of breadsticks now, laying first the long line from Sulzano to Peschiera Maraglio, then the angles from Monte Isola to Isola di San Paolo. The little island is surrounded by carefully broken breadsticks. The piers are taken up and eaten when dinner arrives.

A couple of prawns. A bite of salad. Half a glass of red wine. “Eat,” Jonathan says.

“We sold a big one.”

“How much?”

“One million two.”

“One point two emm?”

“Yes.”

Now the wedge of vanilla cake. Fresh whipped cream.

**********

Art is not an antidote to loss. Just an answer to it. Like the painting of a woman by a lake. Like walking on water for two weeks. Years of daredevil engineering and unnecessary effort for something so ephemeral. He’ll make another trip to Italy. Then back to New York. Then Abu Dhabi. Then New York. Then Italy. More shows. More galleries. More museums. Maybe Colorado. Maybe Abu Dhabi. Maybe.

Tonight he hurries home. He’ll work late.

“There is a madness of things to be done!”

Such a bright, brief complication. And artists do not retire.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jeff_MacGregor2_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d9/51/d951902d-789a-4fba-82b7-8f7f3368ebb1/jun2016_h02_colchristo.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jeff_MacGregor2_thumbnail.png)