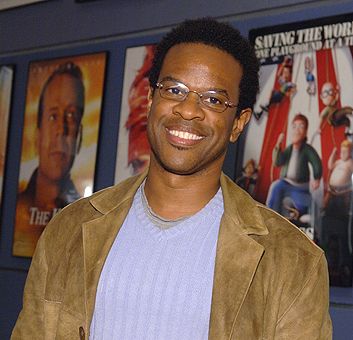

Interview with Thomas Allen Harris

Director of “Twelve Disciples of Nelson Mandela”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/harris_fam.jpg)

When South African policemen shot down student protesters during the Soweto uprising of 1976, the charismatic leader of the African National Congress (ANC), Nelson Mandela, had been imprisoned for more than a decade. But because his followers, ANC freedom fighters, had continued his work outside the country after the ANC was outlawed in 1960, the groundwork was in place for an international war against apartheid.

In his award-winning film Twelve Disciples of Nelson Mandela: A Son’s Tribute to Unsung Heroes, which makes its PBS debut on September 19, 2006, director Thomas Allen Harris pays homage to a dozen such foot soldiers from the city of Bloemfontein, including his stepfather, B. Pule Leinaeng, known as Lee, who devoted their lives to freeing South Africa.

Q: What did the "twelve disciples" contribute, and how did they go about their mission?

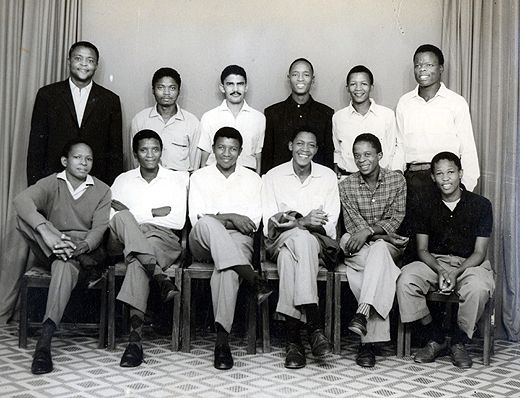

A: They left Bloemfontein in 1960, after the ANC was outlawed. The ANC was aware that it would be outlawed, so they began getting young people to create a resistance outside the country. And the 12 from Bloemfontein are among the first wave of exiles. They helped create structures all over the world that would keep this organization alive. Some of them became soldiers in the [ANC's] army, others started economic institutes, others worked for the ANC exclusively. Lee was the only one of the 12 who decided to try to use media as his weapon of choice.

Q: What inspired you to create this film at this time?

A: The film was inspired by my going to South Africa in 2000 for the funeral of my stepfather, Lee, who had raised me. And during the funeral I heard all these testimonials from the people that left with Lee. These guys were heroes and their stories had not been told and they were old and they were dying. And so I needed to create a eulogy, not only to him but to all the unsung heroes.

Q. I understand they had to trek about 1,300 miles to get to safety?

A. It was very difficult because they had to leave home, and the ANC had no money. Initially, they went to Botswana and were awaiting a plane that would take them to Ghana, which was to be their headquarters. But a war broke out in the Congo, and there was nowhere that small planes in Africa could stop to refuel. So these guys were stranded, and they had to find a way to get outside the purview of the South African authorities who were looking for them. So they went to Tanzania, but it was a harrowing experience. Sometimes they didn't eat for days.

They created pathways that thousands of freedom fighters would follow from Botswana to Tanzania. And from there they went all over the world, both trying to get an education and also to tell people what was going on in South Africa. So when Soweto occurred, there was a structure in place for the anti-apartheid movement.

Q: Soweto students in 1976 were protesting, in part, against the limited education afforded blacks. Weren't some of the limitations enacted while the disciples were still attending school?

A. Yes, initially, the government provided much less money for the education of blacks and coloreds. But with apartheid, they sought to completely disenfranchise the black community. The Bantu education system was based on the idea that the highest level a black person could achieve was to be a servant in a white person's house, or a miner.

Q. A voice-over in the film says that under apartheid one had to either rise up or be buried. Is that Lee's voice we are hearing?

A. Lee came to the United States in 1967 to become a political TV journalist. He was locked out of mainstream journalism, but he kept amazing archives. He archived his radio scripts, all his papers, photography, the short films he made of his exile community. Anytime anyone interviewed him, he would try to keep that audiotape. And in 1989, a filmmaker interviewed him.

So three years into my making this film, my mother found the audiotape. And you can imagine if I hadn't started this film, I never would've looked for this tape. That's how my filmmaking process goes. I begin a journey. I'm not sure where the journey's going to take me—I have an idea but I don't have a set script—I allow for the possibility of finding things along the way because any journey is going to reveal things that one does not know. It's like life. Well, I found this tape, and his voice has become the skeleton of the entire film.

Q. Lee married your mother, Rudean, in 1976. Did they meet while he was studying communications at New York University?

A. He met her before, during a visit to New York. She was very aware of African issues. And she was impressed by him and liked the way he danced.

Q. You've said that early on, you thought of him as a handsome revolutionary who taught you about the horrors of apartheid and the imprisoned leader of the ANC. Why did you later reject Lee as a father?

A. He was a traditional South African father; I was an American son. When you have multicultural families, it's not easy. And we each came with our own baggage. I had been abandoned by my biological father and wasn't very trusting. The irony is that I was of two minds and hearts. When I was in South Africa, I realized, my God, I've come here to say goodbye to my father. Emotionally, I was in denial about our linkage, the depths of it. I was fighting him to a degree, but on another level I was following him. I became a TV journalist and fulfilled a lot of those dreams.

Q. When you were filming him at the house in the Bronx on Father's Day, 1999, he seemed to exude both warmth and distance. Did he keep a distance between himself and others, and did you find that to be the case with other exiles?

A. I think there is a lot of pain in exile, and, yes, there was distance. We couldn't fully understand him, even though we loved him. And, ultimately, when he went back to South Africa, he couldn't just stay in South Africa, because nearly 30 years of his life was here with us. He kept going back and forth, even though my mother moved there with him, because he was vested in both places.

But I noticed as a kid that there was a certain distance. None of us in that house could understand how he experienced living in a place that we called home, and because he had an accent, how he dealt with certain ignorance in America. Or how he dealt with the fact that he didn't have a passport, so he was considered landless—how that affected his sense of power. And then knowing what was happening at home—people were getting killed and tortured and what could he do? And when could he get back to see his family?

Q. But Lee did finally achieve his dream of becoming a broadcaster when the United Nations opened an anti-apartheid center. Can you tell me when he went to work at the UN and what he did there?

A. He was involved in different kinds of UN activities from the time he came here in the late 1960s. But in 1976 they opened the Center Against Apartheid, and he started working there and was hired full time in 1981. The mission of their anti-apartheid media division was to tell the people in South Africa what was happening around the world in terms of the burgeoning anti-apartheid movement. So they would collectively produce these scripts that would be translated into each of the languages of South Africa—and Lee was responsible for transcribing them and recording the Tswana version of the script. His radio show was broadcast from Botswana into South Africa.

Q. Nelson Mandela was released in 1990 and elected president in 1994. When did Lee go back to Bloemfontein to live permanently?

A. He moved there permanently in 1995. He retired from the UN with his pension and built a house in Bloemfontein.

Q. How many of the disciples from Bloemfontein survive today?

A. When I started filming there were seven. Now there are four.

Q. Lee said, "It's nice to be home, but we have a long way to go." Do you think he felt his mission was incomplete?

A. Well, it's a multi-generational struggle. He passed this vision on to me. That's one of the things I realized in going to South Africa, that I had a job to do. And that was one of the main reasons that when I went back, I didn't just make this a historical documentary. I went back and I hired all these young South African actors from Bloemfontein who didn't have any idea this story existed. And so they took this journey with me, and you have all these people now who are thinking about the next step, about what they can contribute. When these disciples got back home, they were old men. You have to pass the baton.

Q. And when will Twelve Disciples reach DVD?

A. On September 19, at the same time as the PBS airing of the film. There are two distributors for the DVD; the educational distributor is California Newsreel. And for the home video, I'm doing self-distribution through my Web site: chimpanzeeproductions.com.