Iris Van Herpen Is Revolutionizing the Look and Tech of Fashion

The Dutch designer redefines what it means to be fashion forward

:focal(530x311:531x312)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/74/bd/74bd9ec8-6387-4e6d-a2ca-6e3ac50e9b65/160730-iris-van-herpen122370-master-cmyk-wr.jpg)

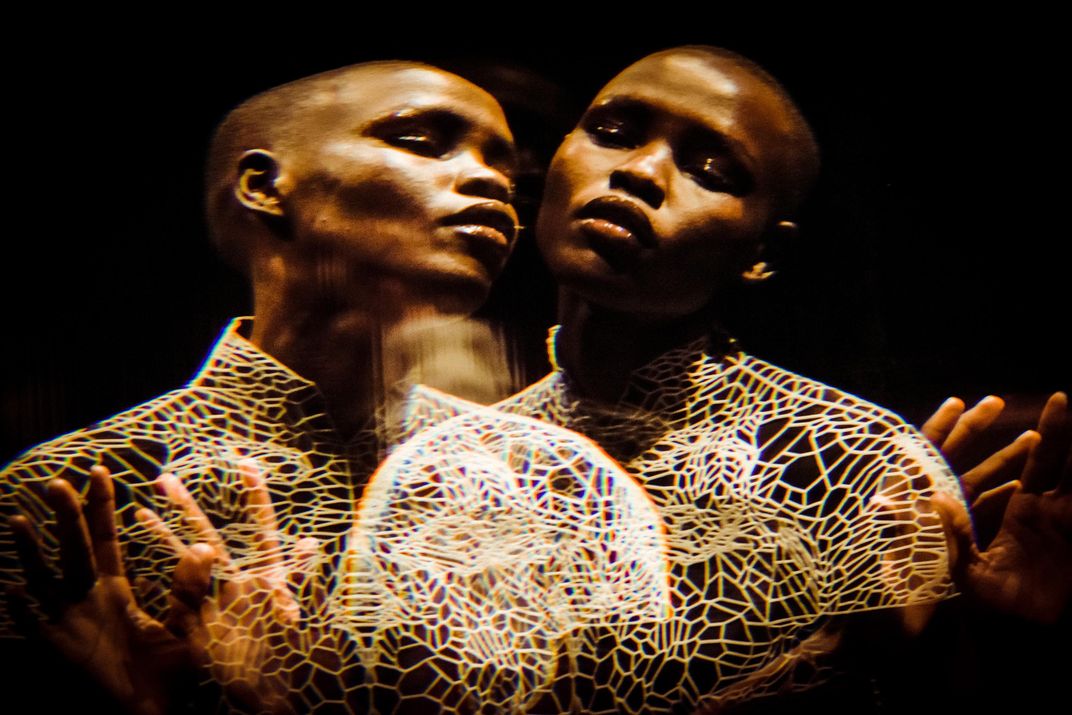

The haute couture works of Dutch fashion designer Iris van Herpen can seem mind-bendingly ahead of their time. At Paris Fashion Week, in March, models in seemingly gravity-defying ensembles strode down a runway dotted with strategically placed optical screens that reflected and distorted

the models’ appearance like high-tech fun house mirrors. Van Herpen’s designs are sleek in a way that calls to mind marvels of evolutionary design, like stingrays or coral, combined with the type of repetitive structures one expects only a machine could produce.

Her silhouettes range from close-fitting to outsized and geometric. One outfit looked like a freeze frame of a dress swept upward by a strong wind. Another, with exaggerated shoulders and hips, had the shape of a moth with its wings spread. The show’s focal dress was made from 5,000 individual pieces, each 3-D printed and then hand-woven together to evoke a glimmering, gothic needlepoint. Van Herpen has been hailed by the New York Times for her “different way of thinking,” a high-concept designer who fuses an interest in fashion, art and architecture with cutting-edge technologies and fields of science as diverse as particle physics, robotics and microbiology. “Iris van Herpen’s astonishing designs don’t look like ‘clothes,’” the Washington Post wrote last year. “They look like the future.”

The 31-year-old van Herpen, who grew up in a small town in Holland, studied fashion design at the esteemed Dutch art academy Artez and had an internship during college with the pathbreaking fashion designer Alexander McQueen. She does think about the future, but less, perhaps, than many of her admirers might expect. “I don’t find my work futuristic,” says van Herpen, in a recent interview with Smithsonian. “It’s bizarre how the mind works. Many of the concepts and explorations happening today,” she says, like those she tries to conjure with the designs she puts on display at her fashion shows, “feel as though they are the future, not yet real.”

The fact that we are seeing them, she believes, proves exactly the opposite, and those most familiar with her work agree. “We’re so quick to cast her work that way, because it seems other, it seems futuristic,” says Sarah Schleuning, a curator at the High Museum, in Atlanta, whose first-ever fashion show, a retrospective of van Herpen’s work, runs until May 15. It may be worth noting that the OCT Contemporary Art Terminal in Shanghai and the OCT Art & Design Gallery in Shenzhen, China, have been showcasing van Herpen’s work in a traveling exhibit called “The Future of Fashion Is Now.”

Sometimes van Herpen’s imagination pushes even the most cutting-edge technologies to their limits. “So many things that I imagine should logically be here by now are not yet here,” she says. Take, for example, van Herpen’s “Water” dress, a translucent, sculptural affair that splashes away from the body in three dimensions like a still image of water hitting a hard surface. Her initial idea was to 3-D-print the dress—she was, after all, the first fashion designer to send the technology down the runway, in 2010, for a top that looked like several interlocking pairs of ram’s horns, which van Herpen calls “a fossil-like structure.”

But the Water dress as she conceived it wasn’t possible to make—3-D printing technicians hadn’t yet developed a transparent material that could print reliably and maintain its structure. Sometimes, van Herpen says, “I imagine a technique or material that doesn’t exist yet. Sometimes it works, and sometimes it doesn’t.” She settled instead on a relatively low-tech method, using a hand-held heating tool not unlike a blow-dryer to soften a sheet of polyethylene terephthalate, a material she says was the “30th or 40th” she tried, and then manipulated it with pliers and by hand to her desired shape.

Part of what makes van Herpen’s approach so novel are the partnerships she forges while designing and executing her otherworldly visions. For a collection called Magnetic Motion, inspired by a visit to the Large Hadron Collider at CERN, in Switzerland, where she learned about forces of attraction and repulsion, she teamed up with architect Niccolo Casas and the California-based company 3-D Systems to finally print a transparent “Ice” dress. The dress is all Sugar Plum Fairy, an ice sculpture’s best impression of lace. “I spoke to the technicians, and they said, ‘99.99 percent, it’s going to fail,’” van Herpen recalled in an interview with the High. “We really pushed the technology, even into a stage where no one believed in it.” The dress was ultimately “printed” using an industrial-scale process called stereolithography and a unique photopolymer-resin blend that had never been used before.

Each of van Herpen’s collections is conceptually coherent and technologically eclectic. The Biopiracy collection was inspired by van Herpen wondering what it means to live at a time when our very genes can be manipulated and patented. It included ensembles that evoked flesh and scales, seeming alive and suggestive of grotesque genetic manipulation. One sweater looked like a cocoon-emergent mutant woolly bear caterpillar, the dark, fuzzy crawler famous among farmers for predicting the weather. The collection’s cornerstone “Kinetic” dress, a collaboration with designer and artist Julia Koerner and 3-D printing company Materialise, was made from silicone-coated 3-D printed feathers, which were laser-cut and stitched to the dress; it made the model wearing it look as though she’d developed a thick set of wings that danced, wisp-like, around her body as she moved. For several designs, van Herpen worked with a nylon-silk weave commonly called “liquid fabric” because it looks like water. The show itself was full of visual high jinks: Models in silvery dresses, curled up like embryos, floated in plastic bubbles suspended along the side of the catwalk, a collaboration with the installation and performance artist Lawrence Malstaf.

A recent collection called Hacking Infinity was inspired by the human quest to live forever at a moment when we are confronted with the dwindling (some say plundering) of natural resources and the promise of life-extending medicines and, potentially, colonizing other worlds. “The idea of terraforming,” van Herpen says, of the concept of manipulating a foreign planet’s ecology to sustain human life, “opens up a whole new world of possibilities to me.” The collection included large circular dresses meant to call to mind planets. Van Herpen worked with a long list of collaborators, including the Canadian architect and designer Philip Beesley, known for his large-scale artworks that integrate synthetic biology, engineering and advanced computation to create “living” sculptures that interact with viewers. For one dress, van Herpen created an ultralight weave of stainless steel, which she then hand-burnished to create shades of orange, yellow, purple and blue, evoking the colors of interstellar nebulae.

Beesley described their collaborations as focused on finding the best techniques for fabricating individual components. “The dialogues are on the one hand practical—laser-cutting and clipping or adhesions or thermal processes,” he said. Vanessa Palsenbarg, a representative of the 3-D printing company Materialise, wrote in an email that these collaborations can take on a life of their own, “to inspire our other customers—in the automotive, consumer goods, aerospace and other industries.” Beesley, too, believes their value goes beyond exploding the conventions typically associated with fashion design by using cutting-edge techniques and materials. “The fertility of these dialogues is that friends in multiple disciplines are exchanging ideas and opening the sense of what the applications can be,” he went on. “What could a dress be? What could clothing offer? It is a wondrous meditation on how we relate to other people, and to the world.”

Van Herpen’s work can be seen in two shows overlapping this month: “Iris van Herpen: Transforming Fashion,” a retrospective of her work at the High Museum, will run until May 15. “Manus x Machina,” a show exploring how designers have reconciled innovations in machine-made clothing with craftsmanship and handiwork, opens May 5 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Her work is also currently on view at the Smithsonian National Design Museum in New York in the "Beauty -- Cooper Hewitt Design Triennial" exhibition.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/3c/ac/3caca68a-d509-422e-8f61-31aea5aba5ba/exh_1149-vanherpen-1-crystallization_o2-wr.jpg)