Is America a Nation of Soul Food Junkies?

Filmmaker Bryan Hurt explores what makes soul food so personal, starting with his own father’s health struggle, in a PBS film premiering tonight

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20130114105055soul_food_junkies-07-press-thumb.jpg)

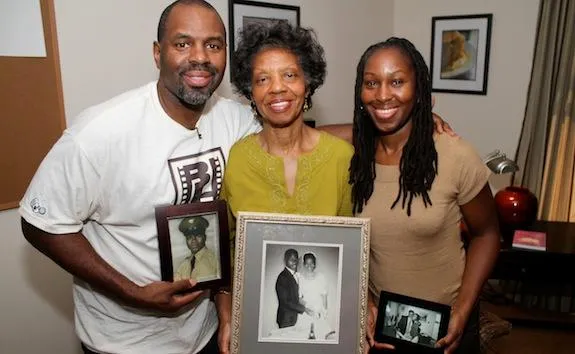

Filmmaker Byron Hurt’s father died at age 63 from pancreatic cancer. To the end, Hurt says, his father loved soul food, as well as fast food, and could not part with the meals he had known since childhood. Hurt began to look at the statistics. The rate of obesity for African Americans is 51 percent higher than it is for whites. He saw a long list of associated risks, including cancers, heart disease and diabetes. Black females and males are more likely to be diagnosed with diabetes, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Looking around at his own community, Hurt had to ask, “Are we a nation of soul food junkies?” The search for an answer led him to his newest documentary, “Soul Food Junkies,” premiering tonight on PBS.

The film includes interviews with historians, activists and authors to create an informative and deeply personal journey through soul food’s history. Hurt unpacks the history of soul food, from its roots predating slavery to the Jim Crow South to the modern day reality of food deserts and struggles for food justice. One woman interviewed, who served Freedom Riders and civil rights activists in her restaurant’s early days, tells Hurt that being able to care for these men and women who found little love elsewhere gave her power.

Now a healthy eater, Hurt says he hopes the documentary can speak to others who find their families facing similar discussions around health, while also telling the story of soul food.

A lot of people give their definitions in the documentary, but how do you define soul food?

When I think about soul food, I think about my mother’s collard greens, fried chicken, macaroni and cheese and sweet potato pies. I think about her delicious cakes, her black-eyed peas, her lima beans and her kale. That’s how I define real good soul food.

Was that what was typically on the table growing up?

It was a pretty typical meal growing up. Soul food was a really big part of my family’s cultural culinary traditions but it’s also a big part of my “family.” If you go to any black family reunion or if you go to a church picnic or you go to an tailgate party, you’ll see soul food present nine times out of ten.

Why do you think it’s persisted and is so popular?

Well, it’s a tradition and traditions really die hard. Soul food is a culinary tradition that has been passed down from generation to generation. People are very emotionally connected to it. When you talk about changing soul food, people become unsettled, territorial, resistant. It’s hard. A lot of people, to be quite honest with you, were very afraid of how I was going to handle this topic because people were afraid that I was going to slam soul food or say that we had to give up soul food and that soul food was all bad.

My intent was really to explore this cultural tradition more deeply and to try and figure out for myself why my father could not let it go, even when he was sick, even when he was dying. It was very difficult for him, so I wanted to explore that and expand it out to the larger culture and say what’s going on here? Why is it that this food that we love so much is so hard to give up?

Where does some of the resistance to change come from?

I think the sentiment that a lot of people have is that this is the food that my grandmother ate, that my great-grandfather ate, and my great-great-grandfather ate, and if it was good enough for them, then it is good enough for me, and why should I change something that has been in my family for generations?

How were you able to make the change?

Through education and awareness. There was this woman I was interested in dating years ago, when I first graduated from college. So I invited her over to my apartment and I wanted to impress her so I decided to cook her some fried chicken. I learned how to cook fried chicken from my mother.

She came over and I had the chicken seasoned up and ready to put into this huge vat of grease that had been cooking and boiling for awhile. She walked into the kitchen and said, “Are you going to put that chicken inside that grease?”

That was the first time that anyone had sort of challenged that. To me it was normal to cook fried chicken. Her mother was a nutritionist and so she grew up in a household where she was very educated about health and nutrition. So she said, this is not healthy. I had never been challenged before, she was someone I was interested in, so from that day forward I started to really reconsider how I was preparing my chicken.

When she challenged you, did you take it personally at first?

I think I was a little embarrassed. It was like she knew something that I didn’t know, and she was sort of rejecting something that was really important to me, so I felt a little embarrassed, a little bit ashamed. But I wasn’t offended by it. It was almost like, “Wow, this person knows something that I don’t, so let me listen to what she has to say about it,” and that’s pretty much how I took it.

How would you describe your relationship with soul food today?

I do eat foods that are a part of the soul food tradition but I just eat them very differently than how I ate them growing up. I drink kale smoothies in the morning. If I go to a soul food restaurant, I’ll have a vegetarian plate. I’ll typically stay away from the meats and the poultry.

The film looks beyond soul food to the issue of food deserts and presents a lot of people in those communities organizing gardens and farmers markets and other programs. Were you left feeling hopeful or frustrated?

I’m very hopeful. There are people around the country doing great things around food justice and educating people who don’t have access to healthy, nutritious foods and fruits and vegetables on how they can eat better and have access to foods right in their neighborhoods…I think that we’re in the midst of a movement right now.

How are people reacting to the film?

I think the film is really resonating with people, especially among African American people because this is the first film that I know of that speaks directly to an African American audience in ways that Food, Inc., Supersize Me, King Corn, The Future of Food, Forks over Knives and other films don’t necessarily speak to people of color. So this is really making people talk.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Leah-Binkovitz-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Leah-Binkovitz-240.jpg)