Is Dippin’ Dots Still the “Ice Cream of the Future”?

How founder and CEO Curt Jones is trying to keep the tiny ice cream beads from becoming a thing of the past

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20130610020055Rainbow-Ice-tmb.jpg)

Curt Jones, founder and CEO of Dippin’ Dots, was always interested in ice cream and science. He grew up on a small farm in Pulaski County, Illinois. As a child, he and his neighbors would get together and make homemade ice cream with an old hand crank: he’d fill up the machine with cream and sugar, add ice and salt to lower the temperature below zero and enjoy the dessert on the front porch.

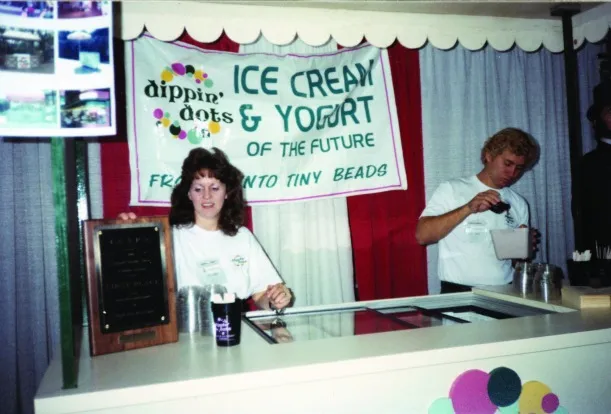

When he first made Dippin’ Dots in 1987, the treat required a little more than a hand crank. By flash-freezing ice cream into tiny pellets with liquid nitrogen, Jones made the ice crystals in his dessert 40 to 50 times smaller than in regular ice cream—something he marketed as “the future” of the classic summer snack. Today, the company sells about 1.5 million gallons of dots a year and can be found in 100 shopping centers and retail locations, 107 amusement parks and more than one thousand stadiums, movie theaters and other entertainment venues across the United States.

But, 26 years after its invention, can we still call it the “Ice Cream of the Future”? Now that competitors including Mini Melts and MolliCoolz caught on and began shaking things up with their own versions of the flash-frozen dessert, has the novelty begun to fade?

In the mid-2000s, when the recession made it difficult for the average amusement-park-goer to drop the extra dollars for the fun dessert, Dippin’ Dots plummeted in sales. In 2007, Dippin’ Dots entered a patent battle with the competitor “Mini Melts” (Frosty Bites Distribution)—a legal defeat that would ultimately contribute to the company’s financial struggles. A federal court jury invalidated Jones’ patent for “cryogenic encapsulation” on a technicality: Jones had sold the product for over a year before filing for the patent. The New York Times cites a memo prepared by the law firm Zuber & Taillieu:

One of the arguments that Mini Melts used in undermining Dippin’ Dots was that the company committed patent fraud by not disclosing that it had sold its ice cream product one year prior to applying for its patent. Technically, an inventor of a new product (or process) is required to apply for a patent within one year of inventing the product or the product is considered to be “public art” and the right to file for a patent is forfeited.

In the suit Dippin’ Dots, Inc. v. Frosty Bites Distribution, LLL aka Mini Melts, it was determined that Jones had sold a similar version of the product he eventually patented to more than 800 customers more than one year prior the filing of the patent, making the company’s claim against Mini Melts unfounded. The Federal Circuit Court ruled that Dippin’ Dots’s method of making frozen ice cream pellets was invalid because it was obvious.

In 2011, Dippin’ Dots filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in federal court in Kentucky. Again, according to the Times, the company owed more than $11 million to Regions Bank on eight different promissory notes. In 2012, Dippin’ Dots secured an offer from an Oklahoma energy executive that would hopefully buy the company out of bankruptcy for 12.7 million dollars. The Wall Street Journal reports:

The deal would preserve the flow of colorful flash-frozen ice cream beads to baseball stadiums and amusement parks across the country…Under the new ownership, the company would continue to pump out the dots from its 120,000-square-foot Paducah, Kentucky, manufacturing plant…

Even with the new owners, the plan was to keep Jones actively involved in the product. To stop the “Ice Cream of the Future” from becoming a thing of the past, the company tried a few twists on the orignal ice cream beads that eventually helped drag the company out of its crushing debt. These days, the company has a few spin off products in the works—a fusion of dots and regular ice cream called Dots N’ Cream and a Harry Potter-themed ice cream at Universal Studios, for example. And by August, Dippin’ Dots will have close to a thousand locations with 40-degrees-below-Fahrenheit freezers installed in grocery stores.

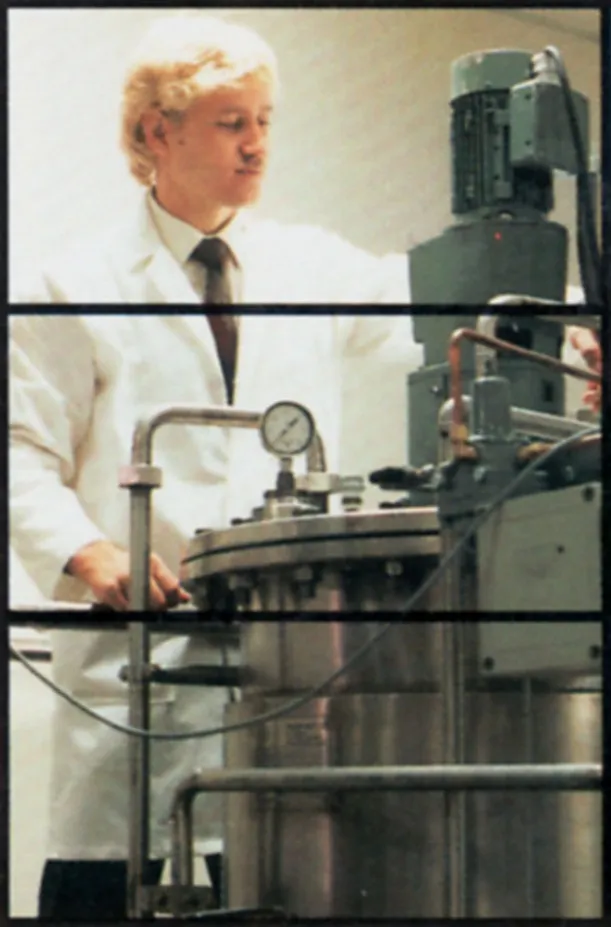

But in the late ’80s, the company was still in its nascent stages. Jones was a Southern Illinois University graduate with a degree in microbiology—a solid foundation for his futuristic idea to take shape. After graduating in 1986, he took a job with Alltech, a biotechnology company based in Kentucky. The science behind the invention is impressive, even 30 years later.

His main responsibility at Alltech was to isolate the probiotic cultures found in yogurt, freeze-dry them into a powder, and then add then to animal feeds as an alternative to antibiotics. Once ingested, these “good bacteria” came back to life and helped with the animal’s digestion. Jones experimented with different ways to freeze the cultures, and he discovered that if he froze the cultures in a faster process, the result was smaller ice crystals. After many attempts, he found that by dipping cultures into liquid nitrogen (a staggering 320 degrees Fahrenheit below zero) he could form pellets—making it easier to pour the small balls of probiotics into different containers.

A couple of months after this discovery, he was making homemade ice cream with his neighbor when they started a casual conversation about ice crystals. Jones loved homemade ice cream since childhood, but he never liked the icy taste—he wished they could freeze the dessert faster. “That’s when the light bulb came on,” Jones says. “I thought, ‘I know a way to do that better. I work with liquid nitrogen.’” Jones immediately began working on this budding business.

In 1988, Jones and his wife opened their creamery in Lexington, Kentucky with zero restaurant experience under their belt, and their rookie mistakes were costly, at least at first.

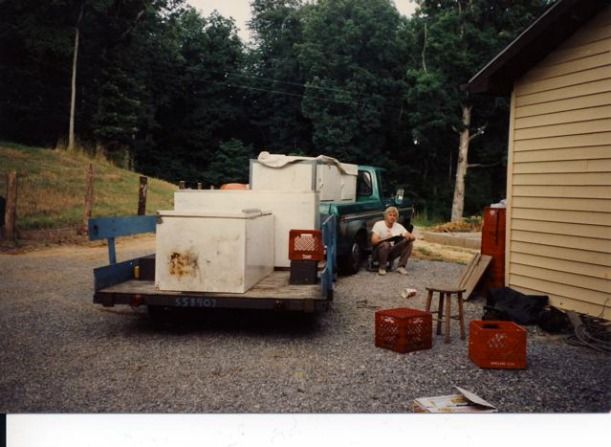

“There just weren’t enough customers coming through the door,” Jones says. “We got by because we sold one of our cars and we had some money saved up.” In that same year, he began converting an old garage on his father’s property into a makeshift factory (pictured below). With the help of his sister Connie, his father and his father-in-law, the Joneses were able to make the conversion.

By 1989, undeterred, Kay and Curt closed their failed restaurant and tried their luck at county and state fairs instead. Success there brought them to Nashville, Tennessee, and Opryland USA. At first, Jones sold the product to the park in designated kiosks throughout Opryland. They were just barely breaking even. The employees at Opryland working the stands didn’t know how to answer questions about the product. “It totally failed the first few years,” Jones says. “The people that tried it liked it, but at that time Dippin’ Dots didn’t mean anything—we didn’t have the slogan yet.” (Sometime between 1989 and 1990, Jones and his sister Charlotte came up “The Ice Cream of the Future” tagline that would help raise the product’s profile.) After two years of terrible sales at Opryland, a new food service supervisor at the park gave Dippin’ Dots another shot. Jones could sell and sample Dippin Dots himself on a retail level and explain the technology to customers himself.

When sales at Opryland took off, Jones pitched the product to other amusement parks, and by 1995 Dippin’ Dots made their international market debut in Japan. In 2000, the company’s network spanned from coast-to-coast.

It’s strange to embrace the nostalgia of a product that garnered a name for itself as a thing of the “future” —ironic even. But for anyone who pleaded with their parents to buy them a bowl of Jones’ straight-from-the-lab ice cream, it’s difficult to imagine Dippin’ Dots going the way of the Trapper Keeper and hypercolor T-shirt.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/561436_10152738164035607_251004960_n.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/561436_10152738164035607_251004960_n.jpg)