Is There a Liberal Bias to Political Comedy?

There is a liberal bias in America’s political comedy scene, says Alison Dagnes. What gives?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Is-there-liberal-bias-political-comedy-631.jpg)

Think about the political comedians performing today. Of those, how many are conservative? Not many, right?

Alison Dagnes, a political scientist, media maven and self-described “comedy dork,” has systematically analyzed the guest lists of late night television shows. She has mined research about which political figures from what side of the aisle comedians target in their jokes. She has studied the history of political humor in this country and interviewed dozens of writers, producers and political satirists about their line of work. In her latest book, A Conservative Walks Into a Bar, Dagnes makes the case that there is a liberal bias in America’s political comedy scene. But, that bias, she says, is no threat to conservatives.

How did you get onto this topic?

I really love political comedy, and this goes back to the early 1990s, when I fell in love with Dennis Miller. After the September 11 attacks, Miller became a very outspoken supporter of George W. Bush. Once I noticed that, I looked around and realized there aren’t that many Republicans out there who are doing political comedy.

I hit upon that reality right when Fox News, in particular, starting getting on Jon Stewart for having a liberal bias. I tried to find some scholarship out there on any kind of bias in political comedy and there wasn’t any. It was lucky for me that a very good friend of mine came up in the ranks at [Chicago improv club] Second City with a bunch of fairly famous people. I asked for her help, and she gave me a bunch of names, and in turn those folks gave me names.

I got to interview several dozens political comedians, writers and producers and ask them my question: Why are there so few conservative political satirists?

You say that there are very understandable reasons that the majority of satirists are liberal. What are these reasons?

Satire is an anti-establishmentarian art form. It is an outsider art. If you mock people who aren’t in power, it isn’t very funny. Satire really is the weapon of the underdog. It is the weapon of the person out of power against the forces in power. It is supposed to take down the sacred cows of politics and differentiate between what is and what should be.

Not only is it an outsider art, but the folks who opt to go into this art form tend to be more liberal. I used to work at C-SPAN, and I watched Brian Lamb, the founder and former CEO of C-SPAN, interview a lot of people. He always asked, “Where did you go to college, and what was your major? So, when I embarked on all of these interviews, I thought, I am just going to do what he did. What I found was that of the 30-something people I interviewed there was not one single person who was a political science major. As political as their material was, they were all performing arts majors or another related field.

Lewis Black has a master's degree from Yale in drama. He told me that political comedians are not interested in being partisans, even though their material could be very, very partisan. They are interested in entertaining. If you go into a field where you are entertaining, you have to expose yourself and be vulnerable. A lot of these qualities do not lend themselves towards the conservative philosophy.

What data did you collect and mine through to determine if there really is a liberal bias in political humor?

I interviewed Jimmy Tingle, a comedian out of Cambridge, Massachusetts, and it was his idea to look at the guest lists of late night shows to gauge whether or not there was some sort of bias afoot. I took one year, and I looked at the guest lists of The Daily Show, The Colbert Report and Wait, Wait…Don’t Tell Me! on NPR.

Overwhelmingly, the people who these bookers want on the shows are celebrities—singers, sports figures and entertainers. The bigger the celebrity, the better. When I looked at the actual political figures, there were more Democratic guests, but it wasn’t by a huge number.

Who do late night hosts target in their jokes? Conservatives or liberals?

The president is going to be the number one target, because he is the person that everybody knows. What comes next are people who are in the news for something that everybody can understand. For example, if a politician is caught in a sex scandal, you can make a very easy joke about that. But the Center for Media and Public Affairs at George Mason University found [in 2010] that there was a split. There were several shows that did lean left with their joke targets a little bit more and then certain shows that did lean right.

What are conservatives to do, with a liberal bias in comedy?

I think conservatives don’t have to worry too terribly much. There really is no barrier to having more conservative political satire out there. While I do understand conservatives’ frustration that the Hollywood establishment is, in their view, perhaps blocking their success, there is nothing that stops you from doing it virally. So, there is one option for conservatives, to get their stuff up on YouTube and get a following.

Also, liberal satirists are not just poking at the conservatives. If you look at the way a lot of these liberal satirists have really just ripped Obama apart, they are not pulling the punches on the left even though they are [positioned] on the left.

In the book, you trace American satire back to the Revolutionary period.

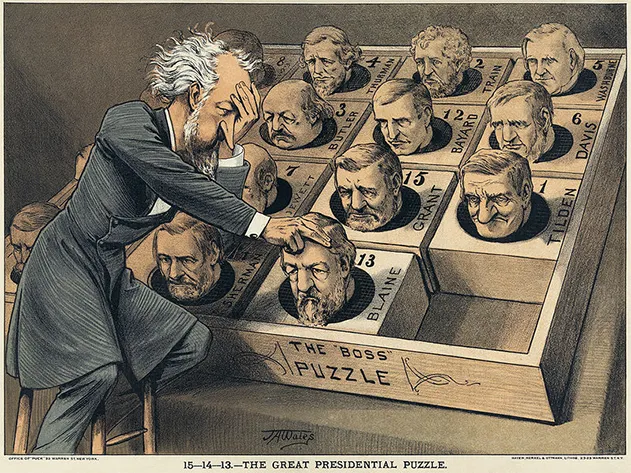

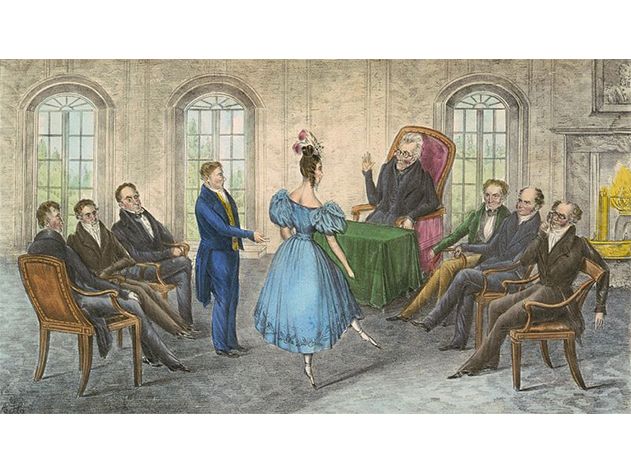

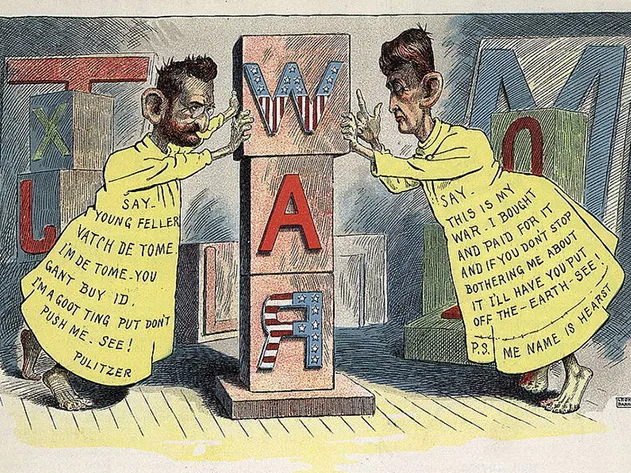

What I loved in taking the big macro view of American political satire, going back before the founding, was how political humor really mirrored the larger political climate of the time. There were points in American history when satire was rich. The Revolutionary War was actually one of them. There was obviously a lot of consternation, but folks like Benjamin Franklin were really able to use wit as a weapon in their writings. You get to the Jacksonian era, which really was a very flat time for political humor, because the context was not amenable for it. You fast-forward to the Progressive Era, where there was this anti-establishment feeling out there, and so, accordingly, this is when political cartoons really rose as a major form of criticism. Obviously, World Wars I and II were terribly frightening times and not ones that were rich in humor, but after World War II when people were starting to feel good again, political humor began to rise. It really does ebb and flow with the larger political context.

Where does political satire stand today?

It is incredibly strong, for many different reasons. First of all, our media system is so enormous, and there are so many different ways to get political humor. You can get tweets from the Borowitz Report [now a part of the New Yorker’s website.] That’s just 140 characters of humor in quick little bursts. You can subscribe to online content from Will Durst or go to The Onion. You can get it from Comedy Central. You can get it from late night humor. You can get it on the radio, on NPR and also on satellite radio. There is just a lot of it out there.

If you and I want to get together and do a comedy show, we can put it up on YouTube. Nothing is going to stop us from doing that. If we want to put out our own political humor on Facebook or on Twitter, we can do that as well. So the obstacles to getting your humor out there are very, very few.

Satire is also rich because we are in a very, very polarized environment right now politically, and with that polarization comes a lot of finger pointing, hostility and nastiness. I think that amidst all this anger, vitriol and distrust there is a lot of room for laughter. It is an easier way to get the hard stuff down, and there is a lot of hard stuff for us to get down.

So, satire can be productive at a time of partisan gridlock?

It can be. If we can laugh together than maybe we can talk to each other a little bit better. I think that political humor can be something that can bring us together as long as everyone understands that it is a joke. When we start taking it too seriously, then it loses its efficacy and moves into a very different category.

In July 2009, Time magazine conducted a poll, as you note in your book, asking its readers to identify the most trusted newsperson in America. The winner was Jon Stewart. How do you feel about this?

I feel mixed. I know that Jon Stewart and his writing staff at The Daily Show do a tremendous job of exposing hypocrisy. They do exactly what satirists are supposed to do. They differentiate between what is and what should be, and that is invaluable. But I think that when their viewers conflate their job descriptions, it is problematic.

You cannot go to Jon Stewart or Stephen Colbert and understand something that is going on that is multifaceted and complicated. What you can do is take existing understanding of these things, go to comedy shows and outlets and get a different angle on it.

I like to give an analogy. I know practically nothing about sports. So, when my husband turns on ESPN, I don’t understand sports better, because they are doing commentary on something that I don’t understand. The same thing goes for any of the satire programs. They are doing comedy on something, and you better have a preexisting understanding of it or else you are not going to get the joke.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)