“It Felt Like a Real Discovery”

Six decades after the death of an unheralded New York City municipal photographer, a researcher stumbles upon his forgotten negatives

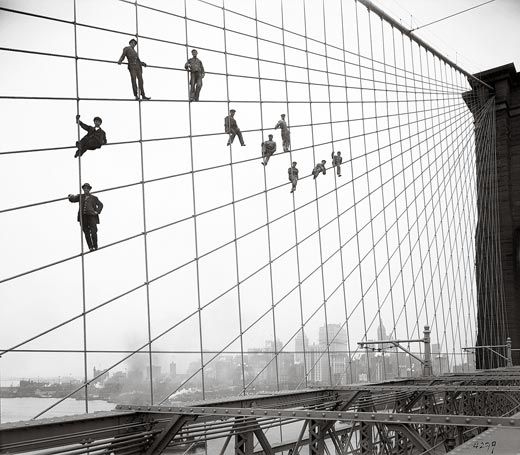

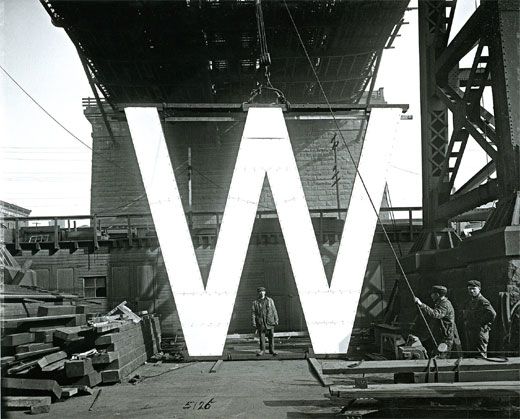

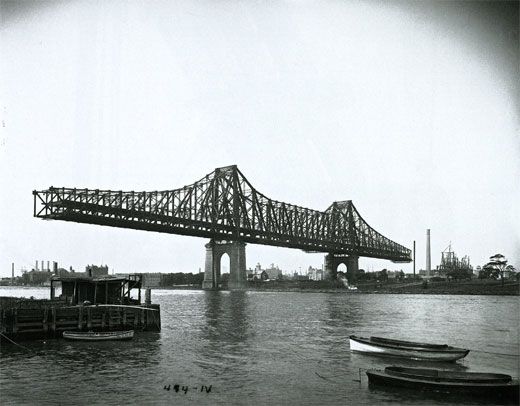

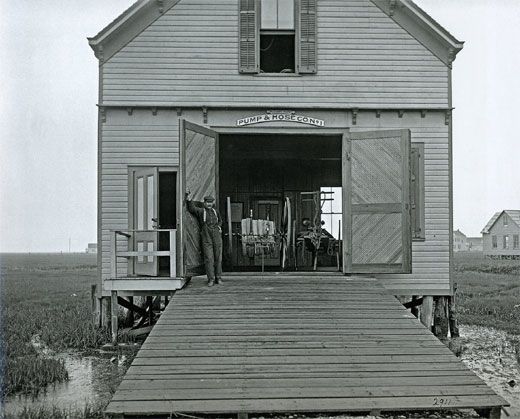

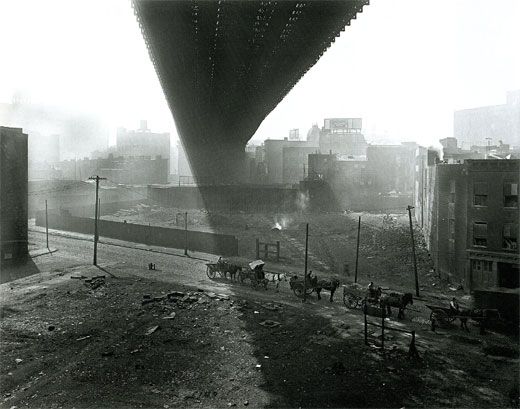

In 1999, Michael Lorenzini, the senior photographer for the New York City Municipal Archives, was spooling through microfilm of the city's vast Department of Bridges photography collection when he realized that many of the images shared a distinct and sophisticated aesthetic. They also had numbers scratched into the negatives. "It just kind of hit me: this is one guy; this is a great photographer," Lorenzini says. But who was he?

It took many months and uncounted hours of trolling through archives storerooms, the Social Security index, Census reports and city records on births, deaths and employment to find the answer: the photographer was Eugene de Salignac, a municipal worker who took 20,000 photographs of modern Manhattan in the making. "It felt like a real discovery," Lorenzini says.

Still, what is known about de Salignac remains limited, and there are no known photographs of him as an adult. Born in Boston in 1861 and descended from French nobility, he married, fathered two children and, after separating from his wife in 1903, started working for the City of New York at age 42. He was the official photographer for the Department of Bridges from 1906 to 1934. At that point, his work—including original plate-glass negatives, corresponding logbooks in his elegant script and more than 100 volumes of vintage prints—began collecting dust in various basement storerooms. He died in 1943, at 82, unheralded.

But de Salignac is now having his day: the Museum of the City of New York is exhibiting his work through October 28, and Aperture has published a related book, New York Rises: Photographs by Eugene de Salignac, with essays by Lorenzini and photography scholar Kevin Moore.

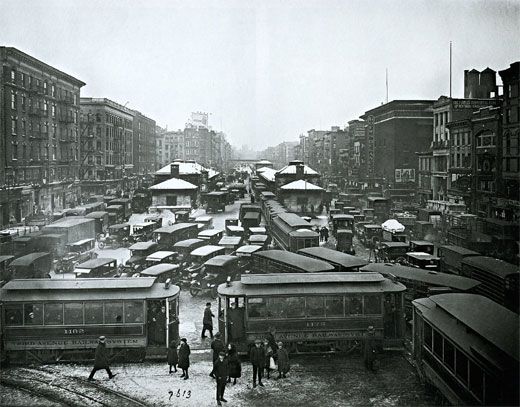

De Salignac's time as a city worker coincided with New York's transformation from a horse-and-buggy town into a modern-day metropolis, and his photographs of towering bridges, soaring buildings, trains, buses and boats chart the progress. "In this remarkable repository of his work, we really see the city becoming itself," says Thomas Mellins, curator of special exhibitions at the Museum of the City of New York. "During this period, New York became a paradigm for 20th-century urbanism, and that has to do with monumentality, transportation systems, working out glitches, skyscrapers, with technology—all of the things that emerge in these photos."

De Salignac's photograph of the Staten Island ferry President Roosevelt coming into port, made in Lower Manhattan in June 1924 with a bulky wooden field camera, typifies his ability to stretch beyond straightforward documentation. "This is not your typical municipal photograph," says Moore. "There's a sense of anticipation—that perfect moment where the boat is about to dock, and a sense of energy, a flood about to be unleashed." Adds Lorenzini: "It shows him thinking like an artist."

De Salignac's pictures have been reproduced in books, newspapers, posters and films, including Ken Burns' Brooklyn Bridge; though largely uncredited, his work helped shape New York's image. "He was a great chronicler of the city, in the tradition of Jacob Riis, Lewis Hine, Stieglitz and Berenice Abbott," says Mellins. "The fact that he was a city employee may have made it less likely that people would think of his work in an artistic context, but these images indicate that he really takes his place in the pantheon of great photographers of New York."

Lorenzini still isn't satisfied. "I'd like to know what he did for the first 40 years of his life, to see a photograph of him as a grown man," he says. "Where did he learn photography? Was he formally trained? Did he consider himself an artist?" Information about him, and prints by him, keep trickling in. Not long ago, a woman mailed to the Municipal Archives ten photographs of New York that she'd bought at a Texas flea market; Lorenzini immediately recognized them as de Salignac's. And a cache of 4,000 de Salignac prints was recently unearthed in the Battery Maritime Building in Lower Manhattan. "There is definitely more to the story," Lorenzini says.

Carolyn Kleiner Butler is a writer and editor in Washington, D.C.