Ivory Merchant

Composer Irving Berlin wrote scores of hits on his custom-built instrument

Among the more than 3,000 songs that Irving Berlin wrote was a tune called "I Love a Piano." A lyric from it goes:

"I know a fine way to treat a Steinway

I love to run my fingers o'er the keys, the ivories..."

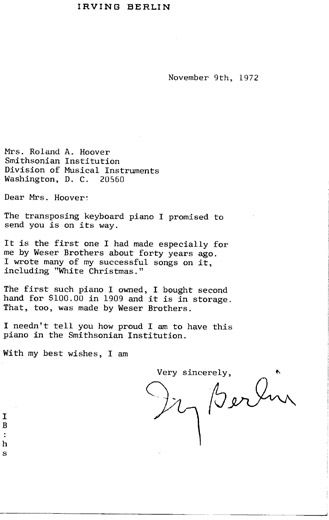

Of course Berlin (1888-1989), who was born 120 years ago this month, had lots of reasons to love a piano: during a long and glittering career, he created such enduring classics as "Alexander's Ragtime Band," "White Christmas," "God Bless America," "Easter Parade" and "Puttin' on the Ritz." A self-taught pianist, he may have tickled the ivories, but he played mostly on the ebonies. And the pianos he used for composing weren't Steinways but specialized transposing pianos. A lever moved the keyboard, causing an inner mechanism to alter notes as they were played into any key he wanted. In 1972, Berlin donated one of these curious devices, built in 1940, to the Smithsonian's National Museum of American History (NMAH).

Dwight Blocker Bowers, an NMAH curator and a musician himself, has played a few tunes on Berlin's piano. "The period around the turn of the century was an age of musical machines and the transposing piano was one of them," he says. "Berlin had a few of these pianos. He called them his ‘Buicks,' and when I worked the mechanism to move the keyboard, it played like an old stick-shift car drives."

Berlin's reliance on the black keys meant he was able to play only in the key of F sharp. It turned out to be a liability. "It's very difficult to play in F sharp," according to pianist-vocalist Michael Feinstein, a preeminent interpreter of America's 20th-century songwriters. "It is a key that is technically limiting."

Berlin's life story—Dickens by way of Danielle Steel—clearly demonstrates, however, that the composer had a gift for overcoming limitations. Born Israel Beilin in Russia, he immigrated to New York City with his family five years later; his father, employed as a cantor in synagogues, died in 1901. As soon as the boy was old enough, he began selling newspapers and busking on the streets of the Lower East Side. As a teenager working as a singing waiter at Pelham's Café in Chinatown, he was asked to write lyrics for a song to compete with other musical restaurants. The result was "Marie From Sunny Italy," and when it was published, it earned the kid 37 cents and a new name: I. Berlin, the result of a misspelling.

Having watched the café's pianist compose "Marie," Berlin promptly sat down and taught himself to play, on the black keys. "It's peculiar," says Feinstein. "Most people would probably start playing in C, on the white keys. It probably wasn't a choice; he started hitting the black keys, and that's where he stayed." Feinstein adds: "What's remarkable about Berlin is his evolution. Listening to ‘Marie From Sunny Italy,' you wouldn't think that there's a musical future there."

Berlin wrote both the music (in F sharp, naturally) and lyrics for the first of his huge hits, "Alexander's Ragtime Band," in 1911. But F sharp was not the key that sheet music publishers wanted—hence the need for a piano that would produce his popular tunes in popular keys.

Berlin's stick-shift Buicks were the medium but not the message. "I don't think [the transposing piano] affected the music itself," says Bowers. "It just let him translate what he was hearing in his head." And what Berlin heard in his head, millions have been hearing in their hearts for nearly 100 years. Once asked about Berlin's place in American music, composer Jerome Kern responded: "Irving Berlin has no place in American music—he is ‘American music.'"

Owen Edwards is a freelance writer and author of the book Elegant Solutions.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)