Jan Lievens: Out of Rembrandt’s Shadow

A new exhibition re-establishes Lievens’ reputation as an old master, after centuries of being eclipsed by his friend and rival

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Lievens-The-Feast-of-Esther-631.jpg)

Telescopes trained on the night sky, astronomers observe the phenomenon of the binary star, which appears to the naked eye to be a single star but consists in fact of two, orbiting a common center of gravity. Sometimes, one star in the pair can so outshine the other that its companion may be detected only by the way its movement periodically alters the brightness of the greater one.

The binary stars we recognize in the firmament of art tend to be of equal brilliance: Raphael and Michelangelo, van Gogh and Gauguin, Picasso and Matisse. But the special case of an "invisible" companion is not unknown. Consider Jan Lievens, born in Leiden in western Holland on October 24, 1607, just 15 months after the birth of Rembrandt van Rijn, another Leiden native.

While the two were alive, admirers spoke of them in the same breath, and the comparisons were not always in Rembrandt's favor. After their deaths, Lievens dropped out of sight—for centuries. Though the artists took quite different paths, their biographies show many parallels. Both served apprenticeships in Amsterdam with the same master, returned to that city later in life and died there in their 60s. They knew each other, may have shared a studio in Leiden early on, definitely shared models and indeed modeled for each other. They painted on panels cut from the same oak tree, which suggests they made joint purchases of art supplies from the same vendor. They established the exotic, fancy-dress "Oriental" portrait as a genre unto itself and later showed the same unusual predilection for drawing on paper imported from the Far East.

The work the two produced in their early 20s in Leiden was not always easy to tell apart, and as time went on, many a superior Lievens was misattributed to Rembrandt. Quality aside, there are many reasons why one artist's star shines while another's fades. It mattered that Rembrandt spent virtually his entire career in one place, cultivating a single, highly personal style, whereas Lievens moved around, absorbing many different influences. Equally important, Rembrandt lent himself to the role of the lonely genius, a figure dear to the Romantics, whose preferences would shape the tastes of generations to come.

"I've often felt that Rembrandt tended to lead Lievens toward stronger observation, and Lievens, who seemed keener on current ideas in the Dutch art world, helped Rembrandt broaden his horizons," says Walter Liedtke, curator of European paintings at Manhattan's Metropolitan Museum of Art. "Once the two artists leave Leiden, Lievens becomes a very different, more international but shallower figure on the London and Antwerp stages." By the 19th century, Lievens had fallen into such deep obscurity as to be lucky to be mentioned at all, even as a pupil of Rembrandt's, which he never was.

With the current tour of the new international retrospective "Jan Lievens: A Dutch Master Rediscovered," Lievens' induction to the pantheon of old masters may at last be at hand. From its opening at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. last fall, the show has moved on to the Milwaukee Art Museum (through April 26) and is scheduled to make a final stop at the Rembrandthuis in Amsterdam (May 17-August 9).

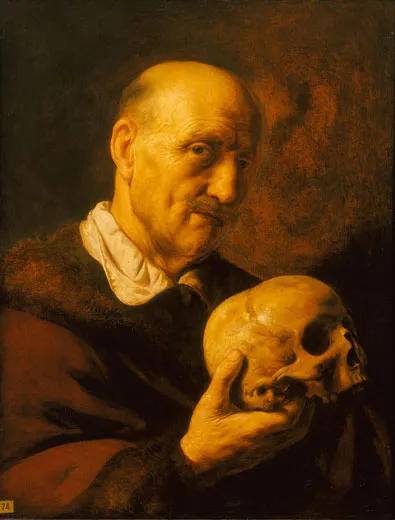

While Lievens' name will be new to many, his work may not be. The sumptuous biblical spectacular The Feast of Esther, for instance, was last sold, in 1952, as an early Rembrandt, and was long identified as such in 20th-century textbooks. It is one of more than 130 works featured in the exhibition—from celebrations of the pleasures of the flesh to sober, meditative still lifes and the brooding Job in His Misery, which captures the frailty of old age compassionately yet unsentimentally. In surrounding the all-too-human central figure of Job with images of a witch and hobgoblins, Lievens anticipates Goya. In The Raising of Lazarus, he stages the Gothic scene in a somber palette and with the utmost restraint—Jesus abstaining from grand gestures, Lazarus visible only as a pair of hands reaching skyward from the tomb. Like Rembrandt, Lievens uses pale, glimmering light to suffuse the darkness with intimations of spirituality.

These examples, in so many genres, are hardly the works of an also-ran. "We've always seen Lievens through the bright light of Rembrandt, as a pale reflection," says Arthur K. Wheelock Jr., curator of northern Baroque paintings at the National Gallery. "This show lets you embrace Lievens from beginning to end, to understand that this man has his own trajectory and that he wasn't always in the gravity pull of Rembrandt." Wheelock has been particularly struck by the muscularity and boldness of Lievens, which is in marked contrast to most Dutch painting of the time. "The approach is much rougher, much more aggressive," he says. "Lievens was not a shy guy with paint. He manipulates it, he scratches it. He gives it a really physical presence."

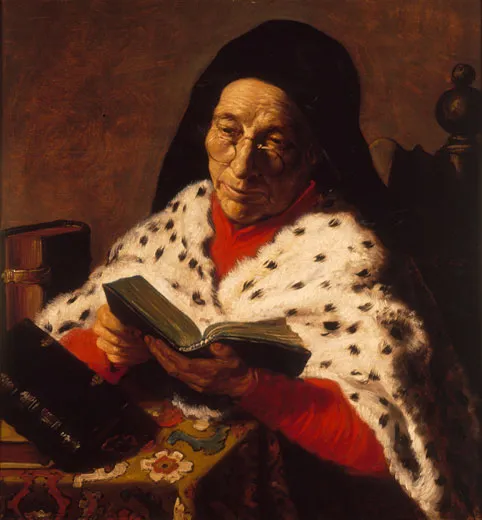

Though the Leiden public of Lievens' youth had a high regard for the fine arts, the beacon for any seriously ambitious artist was Amsterdam. Lievens was duly sent there by his father at the tender age of 10 to study with the painter Pieter Lastman, grand master of complex narrative scenes taken from ancient history, classical mythology and the Bible. Still a boy when he returned to Leiden two years later, Lievens lost no time establishing a studio in his family home. The date of his Old Woman Reading is uncertain, as is his chronology in general, but scholars place it somewhere between 1621 and 1623, meaning he was just 14 to 16 years old when he painted it. It is a performance of amazing precociousness, as remarkable for the thoughtful expression on the wrinkled face (possibly his grandmother's) as for the effortless depiction of such details as the lenses of her spectacles and the fur of her wrap.

Throughout his early period in Leiden, Lievens worked in a style that was brash and bold: his paintings were on a grand scale, the lighting theatrical, the figures larger than life. In many of these respects, he seems less the disciple of Lastman than of one of the Dutch followers of the revolutionary Italian painter Caravaggio. Dubbed Caravaggisti, these artists had recently returned north from a long stay in Rome and were active in nearby Utrecht. Scholars have yet to discover when and how Lievens fell under the Caravaggisti's spell, but his pictures, with their sharp contrasts of light and dark, expressive gestures and flair for drama, leave little doubt that he did.

In the mid-1620s, Rembrandt, too, headed to Amsterdam to apprentice with Lastman. Six months later, he came home, and from then on, the two young artists likely viewed themselves as equals if not rivals. Rembrandt must have felt a twinge of envy in the winter of 1631-32 when the Flemish master Anthony Van Dyck painted Lievens' portrait and not Rembrandt's. To make matters worse, that likeness later appeared, engraved, in Van Dyck's Iconography, a who's who of celebrities of the art world.

Lievens painted The Feast of Esther around 1625, about the time Rembrandt returned to Leiden. It is approximately four and a half by five and a half feet, with figures shown three-quarter length, close to the picture plane. (At that time, Rembrandt favored smaller formats.) At the luminous center of the composition, a pale Queen Esther points an accusing finger at Haman, the royal councilor who is plotting to exterminate her people. Her husband, the Persian King Ahasuerus, shares her light, his craggy face set off by a snowy turban and a mantle of gold brocade. Seen from behind, in shadowy profile, Haman is silhouetted against shimmering white drapery, his right hand flying up in dismay.

Silks, satins and brocades, elegant plumes and gemstones—details like these give Lievens ample scope to show off his flashy handling of his medium. Not for him the fastidious, enamel-smooth surfaces of the Leiden Fijnschilders—"fine painters," in whose meticulously rendered oils every brush stroke disappeared. Lievens reveled in the thickness of the paint and the way it could be shaped and scratched and swirled with a brush, even with the sharp end of a handle. This tactile quality is one of Rembrandt's hallmarks as well; there are now those who think he picked it up from Lievens.

Close in time and manner to The Feast of Esther is Lievens' Pilate Washing His Hands. The young man pouring the cleansing waters from a golden pitcher resembles Rembrandt's youthful self-portraits closely enough to suggest that Rembrandt was in fact the model. The highlights that play over the gold are mesmerizing, and the glaze of the water as it flows over Pilate's hand is as true to life as a photograph. But above all, one is transfixed by Pilate, who looks the viewer straight in the eye, which Rembrandt's figures seldom, if ever, do.

The earliest known comparison of Lievens and Rembrandt comes down to us in a memoir by the Dutch statesman and patron of native talent Constantijn Huygens. Written around 1630, it described an encounter with the two artists, then in their early 20s: "Considering their parentage, there is no stronger evidence against the belief that nobility is in the blood....One of our two youths [Lievens] was the son of a commoner, an embroiderer, the other [Rembrandt], a miller's son....I venture to suggest offhand that Rembrandt is superior to Lievens in his sure touch and liveliness of emotions. Conversely, Lievens is the greater in inventiveness and audacious themes and forms. Everything his young spirit endeavors to capture must be magnificent and lofty....He has an acute and profound insight into all manner of things....My only objection is his stubbornness, which derives from an excess of self-confidence. He either roundly rejects all criticism or, if he acknowledges its validity, takes it in bad spirit."

At their first meeting, Lievens expressed a desire to paint Huygens' portrait, and Huygens invited him to visit The Hague, then the Dutch capital, for that purpose. For years to come, the statesman would be a steadfast Lievens supporter, throwing several courtly commissions his way.

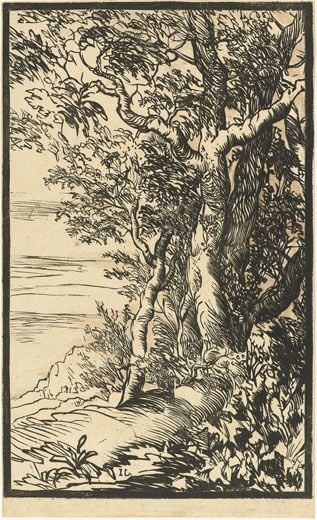

Around 1632, Rembrandt relocated to Amsterdam for good, while Lievens struck out for London, hoping for work at the court of King Charles I. He apparently did several portraits, now lost, of the royal family, including one of the king. About three years later, he left London for Antwerp, where he found a congenial artistic community, busied himself making prints and drawings, taught himself to do woodcuts and undertook various commissions for Jesuit churches. In Antwerp he married Susanna Colijns de Nole, a Catholic and the daughter of a noted sculptor who had worked with the Jesuits. Lievens may have converted to her religion at that time, less for reasons of faith than as a career move. The couple had a son, Jan Andrea, who grew up to be a painter and, on at least one occasion, his father's collaborator.

In 1644 Lievens moved on again, showing up over the next years in Amsterdam, The Hague and Leiden, as opportunities arose. At last, his lifelong dream of a career creating large-scale extravaganzas for princely dwellings was coming true. Widowed shortly after his return to the Netherlands, Lievens married Cornelia de Bray, the daughter of an Amsterdam notary, in 1648.

After Lievens' departure for England, the bold style of his early work had largely fallen from favor with Dutch government officials and the fashionable clientele at court. They now preferred the more polished Italianate manner practiced by Van Dyck and Peter Paul Rubens, painter to the most illustrious crowned heads of Europe. Rembrandt continued to hone his darkling style, which may have cost him business. But the pragmatic Lievens did his best to move with the times, adapting his style to satisfy many patrons.

Coincidentally, both Rembrandt and Lievens wound up living along an Amsterdam canal called the Rozengracht during their final years. Rembrandt by this time was reduced effectively to working for room and board—his common-law wife and Titus, his only surviving son, had taken control of his finances. Lievens ended up in sad straits, too. Though demand for his work remained strong, financial mismanagement had left him deep in debt.

As an artist, Lievens never stopped assimilating new influences, which made his own style less distinctive as time went on. But even if he made his mark most memorably as the brash Young Turk of his Leiden days, he never lost his capacity to surprise. In the current show, two scenes of lowlife from his Antwerp period (A Greedy Couple Surprised by Death and Fighting Cardplayers and Death) explode with verve and violence. In a different vein, Gideon's Sacrifice shows an angel gently touching the tip of his wand to an altar to ignite a sacrificial flame. Long lost, the painting resurfaced on the art market in Rome in 1995, attributed to a lesser artist of the Italian Renaissance. Now it is given to Lievens as a work of the early 1650s—an ingenious combination of elements from various periods of his career. No longer invisible, Rembrandt's companion star is shining with a luster all its own.

Matthew Gurewitsch's articles on culture and the arts appear frequently in the New York Times and Smithsonian.