Shine On: Jeff Koons in Bilbao

Frank Gehry’s titanium-clad Guggenheim plays host to a stunning survey of Koons’s larger-than-life career

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/08/26/0826af23-eec2-4699-a3e1-e3773dcaf964/puppy_koons-bilbao-2014_web-resize-800x600.jpg)

Swooping along a riverbank in Spain’s Basque Country, the titanium-clad Guggenheim Museum Bilbao is guarded by a giant, flower-covered West Highland white terrier, a breed the American Kennel Club describes as “exhibiting good showmanship” and “possessed with no small amount of self-esteem.” The same can be said of the canine’s creator, artist Jeff Koons, who recently reunited with the sculpture as the museum unveiled an exhibition that brings together nearly four decades’ worth of his diverse, yet unmistakable work.

“With a work like Puppy, I hope that the public feels like they are participating in a Dionysian festival,” says Koons in his signature cadence: a honeyed, hypnotic lilt that is halfway between kindergarten teacher and cult leader. “And I hope that there are hints of that when you go through the exhibition. What I try to accomplish with my work is to have a dialogue on a grand scale—about internal life and the external world, how we can enrich our lives, how we can all participate in transcendence.”

Surpassing expectations is also Bilbao’s claim to fame. The Guggenheim’s 1997 debut there, in its dazzling Frank Gehry-designed home, sent cities around the world scheming to replicate the culturally driven civic reinvention that was soon dubbed “the Bilbao effect” (in Bilbao, it is known as “the Guggenheim effect”). “Puppy was one of the first works we acquired,” says Juan Ignacio Vidarte, director of the Guggenheim Bilbao. “It has become a symbol of our collection and museum—and the whole city.”

According to Vidarte, the museum saw “not just an opportunity but almost a duty” to bring the Koons retrospective to Bilbao—its final stop following presentations at New York’s Whitney Museum and the Centre Pompidou in Paris. “The spaces make it possible to see Jeff Koons’ work as it has never been seen before,” he adds.

On view through September 9 in the museum’s vast, sculptural galleries, the survey unfolds chronologically. Each series of work—artfully displayed vacuum cleaners and tanks of floating basketballs to monumental sculptures and meticulously produced paintings layered with cultural references—is presented so as to encourage not only contemplation but connection, revealing the coherence of an oeuvre that can appear to be unified only by ambition and the pleasures of finely calibrated exaggeration.

“What could be a better setting than the Guggenheim in Bilbao for an artist who blends the baroque on the one hand with modern styles?” says Scott Rothkopf, the Whitney curator who organized the exhibition with the Guggenheim’s Lucia Agirre. “To see the work in Gehry’s building, it just brings out so many of these interesting tensions that are at the heart of Jeff’s work.”

Born in York, Pennsylvania, in 1955, Koons credits art with giving him “a sense of self”—or at least, at the age of three, the confidence that he could do something better than his older sister. By eight years old, he was copying Old Masters and watching his work sell—to customers of his father, an interior decorator who would display the paintings in the windows of his home furnishings store. The family business also provided an early education in the power of display. “I was brought up around objects and brought up to think about how objects make you feel,” notes Koons.

An enduring fascination with Dada and Surrealism (at 18, he spent an afternoon in Manhattan with Salvador Dalí and still recalls “his buffalo fur coat, his diamond-studded tie, and that mustache!”) fueled Koons through art school at the Maryland Institute College of Art in Baltimore and the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, where he delved into art history and studied under Jim Nutt and Ed Paschke. Yet his epiphany came after he moved to New York in late 1976 and, immersed in the downtown scene, “became bored with the idea of making works inspired by my dreams.”

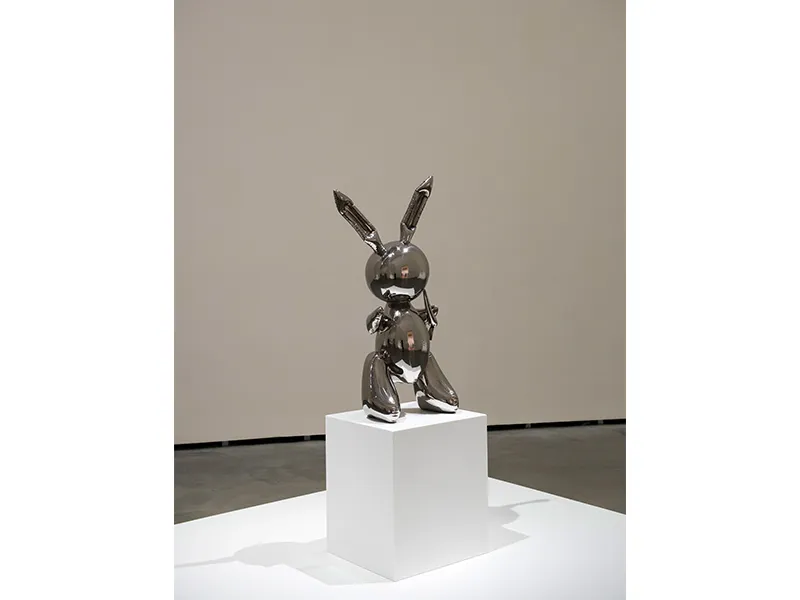

It’s at this point that the retrospective begins, with the "Inflatables" series of 1978 and 1979 that, in their juxtaposition of colorful blow-up flowers and rabbits with store-bought mirrors, prefigure the polished stainless steel forms such as Rabbit (1986) for which Koons is best known. These first galleries, encompassing Plexiglas-encased cleaning machines, mounted billboards, and the “Equilibrium” series that Rothkopf describes as “a meditation on race, social and artistic attainment, life and death” show Koons finding his way around and finally through Marcel Duchamp’s concept of the “readymade” to forge his own path.

Koons’s breakthrough is apparent from his first cast objects: a group of 1985 sculptures that includes life-preserving devices such as an aqualung and a life raft remade in decidedly non-buoyant bronze. These dusky brown forms show the darker side of the artist’s favorite themes of “life energy,” “participation,” and “procreation,” while demonstrating his canny use of material to produce a heightened reaction. “If the material does not provoke an exaggerated state, it’s like a non-experience,” explains Koons, “just such a casual, everyday experience that people aren’t even aware they are having it—and that’s not great art.”

He pushes this theory further in subsequent series, casting both precious and quotidian objects in workaday stainless steel polished to a mirror finish and embarking on “Banality,” a series of stunningly eerie sculptures that exalt kitsch fragments—a Cabbage Patch Kid, Michael Jackson and his pet chimpanzee, and the figure of Buster Keaton astride a tiny horse—into a strange new realm. This is Koons’s version of empowerment: a call for an end to judgment and anxiety about guilty pleasures. “I wanted to let people know that everything in their cultural past is perfect,” he says with a serene smile.

His aim was similar with the “Made in Heaven” series, in which Koons cavorts with the Italian porn star Cicciolina (Ilona Staller, who he would later marry and then acrimoniously divorce). Panned by critics, the series serves as a potent reminder of the sexual force coursing through all of Koons’s work, from his references to female and male fertility figures (the Venus of Willendorf, a wandering peddler known as Kiepenkerl) to the pumped-up characters of Popeye and the Incredible Hulk.

Koons’s grand motivations come together with technical innovation most powerfully in his "Celebration" series, represented in Bilbao by a gallery starring the hot-pink Balloon Dog (1994-2000) that has been exhibited at Versailles and presided over Venice’s Grand Canal. Positioned at the center of the soaring space, the sculpture is a 10-foot-tall version of an ephemeral party toy made precious and permanent—unless it is a contemporary version of an equestrian statue, or a kind of shiny, sexy Trojan horse. “Everything remains in play,” says Koons. “From a young age I tried to take the responsibility to present my work to people so that they could see the starting point. The viewer always finishes the work of art, so they always have the last word.”

"Jeff Koons: A Retrospective" will be on view at the Guggenheim Bilbao in Bilbao, Spain, through September 27, 2015.

Jeff Koons: A Retrospective (Whitney Museum of American Art)