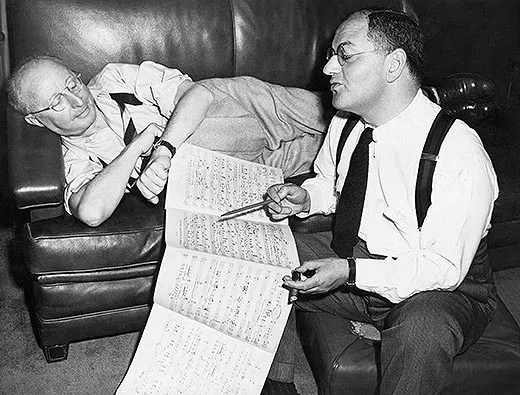

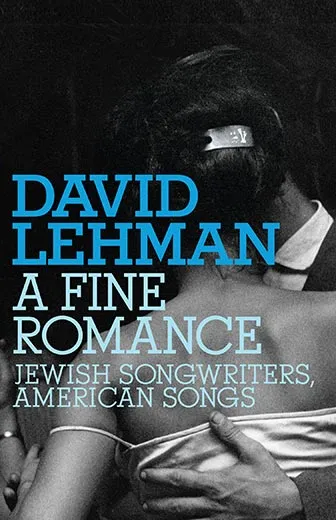

Jewish Songwriters, American Songs

Poet David Lehman talks about the brilliant Jewish composers and lyricists whose work largely comprises the great American songbook

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Irving-Berlin-singing-Los-Angeles-631.jpg)

By 1926, Cole Porter had already written several Broadway scores, “none of which had, well, scored,” poet and critic David Lehman points out. But one enchanted evening that year, while dining in Venice with Noel Coward, Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart, Porter confided that he had finally figured out the secret to writing hits. “I’ll write Jewish tunes,” he said.

“Rodgers laughed at the time,” Lehman writes in his new book, A Fine Romance: Jewish Songwriters, American Songs (Schocken/Nextbook), “but looking back he realized that Porter was serious and had been right.” The minor-key melodies of such famed Porter tunes as “Night and Day,” “Love for Sale” and “I Love Paris” are “unmistakably eastern Mediterranean,” Rodgers wrote in Musical Stages, his autobiography.

Porter’s songs may have had a Yiddish lilt to them, but they are squarely within the mainstream of the great American songbook: that wonderful torrent of songs that enlivened the nation’s theaters, dance halls and airwaves between World War I and the mid-1960s. What’s more, as Lehman acknowledges, many of the top songwriters—Cole Porter included—were not Jewish. Hoagy Carmichael, Johnny Mercer, Duke Ellington, George M. Cohan, Fats Waller, Andy Razaf, Walter Donaldson and Jimmy McHugh come to mind right away.

And yet it is a remarkable fact that Jewish composers and lyricists produced a vastly disproportionate share of the songs that entered the American canon. If you doubt this, consider, for example, a typical playlist of popular holiday records—all of them by Jewish songwriters (with the exception of Kim Gannon): “White Christmas” (Irving Berlin); “Silver Bells” (Jay Livingston and Ray Evans); “The Christmas Song,” a.k.a. “Chestnuts Roasting on an Open Fire” (Mel Tormé); “Let It Snow! Let It Snow! Let It Snow!” (Sammy Cahn and Jule Styne); “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer” (Johnny Marks); and “I’ll Be Home for Christmas” (Walter Kent, Kim Gannon and Buck Ram). Warble any number of popular tunes, say “Summertime” (George and Ira Gershwin), “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes” (Jerome Kern and Otto Harbach) or “A Fine Romance” (Kern and Dorothy Fields)—and it’s the same story. Then of course, there are the Broadway musicals, from Kern’s Show Boat to Rodgers and Hammerstein’s South Pacific to West Side Story, by Leonard Bernstein and Stephen Sondheim.

Lehman, 61, editor of The Oxford Book of American Poetry and the annual Best American Poetry series, has been captivated by this music and its ingenious lyrics since childhood. “It was the songbook to which I responded, not the Jewish identity of its authors,” he writes, “though this was a source of pride to me, the son of refugees.” A Fine Romance, then, reads as a sort of love letter from a contemporary poet to a generation of composers and wordsmiths; from a devoted son to his late parents, who escaped the Nazi onslaught just in time, as his grandparents had not; and finally, to America itself, which allowed the great songwriters and the author himself to flourish in a world of freedom and possibility unlike anything their families had left behind. Lehman spoke with writer Jamie Katz.

Songs like Irving Berlin’s "God Bless America" and Harold Arlen and Yip Harburg’s "Over the Rainbow" virtually defined a national ethos. Do you feel the Jewish songwriters created a kind of religion of American-ness?

In a way they did. Many were the children or grandchildren of people who escaped from the pogroms of Europe and other depredations, and reinvented themselves as Americans. In the process they kind of reinvented America itself as a projection of their ideals of what America could be. We have a secular religion in the United States that transcends all individual religions. This is not entirely an unmixed blessing, but I think that’s exactly what the songwriters were doing.

You talk about how popular song helped uplift and unify Americans through the crises of the 1930s and '40s. On a more subtle level, you suggest that Jewish songwriters were pressing back against the forces that sought to annihilate them. How so?

There are many examples of Depression-era songs that staked out common ground in hard times, like "On the Sunny Side of the Street" or "Brother, Can You Spare a Dime"—often with a mixture of melancholy and resolute good cheer. In 1939 you get The Wizard of Oz, a fantasy about this magical land over the rainbow, on the other side of the Depression. With Oklahoma! in 1943, at the height of the war, when the chorus picks up Curly’s refrain—We know we belong to the land / And the land we belong to is grand!—you feel this great surge of patriotism. "God Bless America" made its debut on the radio with Kate Smith on November 11, 1938, exactly 20 years after the armistice ending World War I. And it was the same day that people read the newspapers about the terrible pogrom known as Kristallnacht in Germany and Austria. While the two had no direct relation, it's impossible to see the two facts as entirely unconnected. Irving Berlin created a song that people authentically like and turn to in time of crisis, as in the days after 9/11/01. The Nazis did battle not only with tanks and well-trained soldiers and the Luftwaffe. They also had a cultural ideology, and we needed something for our side to fight back. That song was one way that we fought back.

Apart from the fact that so many songwriters were Jewish, what is it that you consider Jewish about the American songbook?

To me there's something explicitly or implicitly Judaic about many of the songs. Musically there seems to be a lot of writing in the minor key, for one thing. And then there are instances in which lines of songs closely resemble musical phrases in the liturgy. For example, the opening verse of Gershwin’s "Swanee" seems to come out of the Sabbath prayers. "It Ain't Necessarily So" echoes the haftorah blessing. It's no coincidence that some of the top songwriters, including Harold Arlen and Irving Berlin, were the sons of cantors. There are also other particularities about the music, bent notes and altered chords, that link this music to the Judaic tradition on the one hand, and to African-American forms of musical expression on the other. At the same time, the lyric writers set store by their wit and ingenuity, and one could argue that a particular kind of cleverness and humor is part of the Jewish cultural inheritance. It may well be that people will argue this point, and there are people who know a great deal more than I do about music. You have to trust your instincts and your judgment. But I don't think it's a hanging offense if you're wrong. And I think it's a good idea to be a little provocative and stimulate a conversation about such matters.

As a poet, how do you regard the artistry of the great lyricists?

The best song lyrics seem to me so artful, so brilliant, so warm and humorous, with both passion and wit, that my admiration is matched only by my envy. I think what songwriters like Ira Gershwin, Johnny Mercer and Larry Hart did is probably more difficult than writing poetry. Following the modernist revolution, with T.S. Eliot and Ezra Pound, we shed all sorts of accoutrements that had been thought indispensable to verse, like rhyme and meter and stanzaic forms. But these lyricists needed to work within boundaries, to get complicated emotions across and fit the lyrics to the music, and to the mood thereof. That takes genius.

Take "Nice Work If You Can Get It" by George and Ira Gershwin. There’s a moment in the verse where it goes: The only work that really brings enjoyment / Is the kind that is for girl and boy meant. Now, I think that's a fantastic rhyme. Just a brilliant couplet. I love it. Or take "Love Me or Leave Me," from 1928, with lyrics by Gus Kahn and music by Walter Donaldson: Love me or leave me and let me be lonely / You won’t believe me but I love you only / I’d rather be lonely than happy with somebody else. That is very good writing, with lovely internal rhymes. And you're limited to very few words; it's like writing haiku. But they rhyme and can be sung. Well, I say that's pretty good.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jamie-Katz-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jamie-Katz-240.jpg)