Joe Temperley’s Ageless Sax

The Scottish baritone saxophone musician recalls his 60-year career and the famous singers he’s accompanied

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Joe-Temperley-playing-baritone-sax-631.jpg)

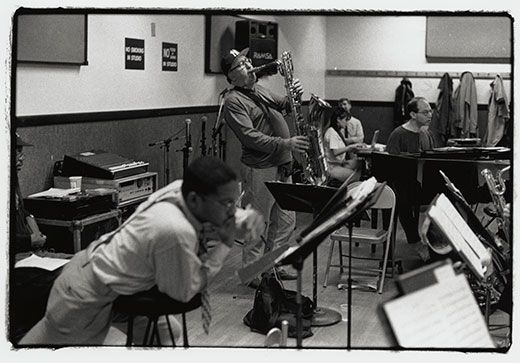

Slinking in through the heavy doors of a big rehearsal space just off New York’s Columbus Circle, I’m filled with awed glee. Nothing compares to watching a great jazz band at work—especially when Wynton Marsalis, Music Director of the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra (JLCO), is in the room.

The 15 band members sit on cushioned chairs, arranged in rows on a broad maple floor: saxes in front, trombones in the middle, trumpets (including Marsalis) in back. Drums, an acoustic bass and grand piano stand to the side. Three days before their fall tour begins, the JLCO is practicing a multilayered piece called Inferno. It was written by musician Sherman Irby, who’s also conducting. Inferno is a difficult piece, and Irby is trying to get the tempo just right.

There’s no doubt that Marsalis, one of the world’s most gifted jazz trumpeters, is the creative engine of this band. But its heart is located two rows forward. Joe Temperley, 82, lifts his heavy baritone sax with the weightless ease of an elephant raising its trunk. He blows a few bars, his rich, resonant tone unmistakable even in this crowded room. Irby points at him with the fingers of both hands.

“There! That’s it. That’s what I’m talking about.”

Born in the mining community of Lochgelly, Scotland in 1929, Temperley is not quite the oldest professional saxophone player in America. Alto sax player Lou Donaldson was born in 1926; Frank Wess in ’22. But Joe, who recently celebrated his 82nd birthday, is the nation’s senior baritone sax artist, and one of the true anchors of the global jazz scene.

“Joe is one of the greatest baritone saxophone players that ever lived, the biggest sound that you ever want to hear,” says Sherman Irby. “And he's still inquisitive, he's still learning, he's still finding new stuff to work on.”

In person, Joe gives an impression of stability, solidity. He’s one of those musicians who have come to look like their sound. His horn of choice is a vintage Conn that he’s had about 50 years. But his first sax was a 14th-birthday gift from his older brother, who played the trumpet. From that point on, Joe was on his own. “I didn't have many lessons,” he says. “All the stuff that I learned, I learned by doing.”

Temperley left home at 17 and found work in a Glasgow nightclub. Two years later, he went to London. His arc across the UK—then the Atlantic—was an odyssey not only between lands, but between musical aspirations. After eight years in England, playing with Humphrey Lyttelton’s band, he was primed for a change.

“In 1959 we toured the United States,” Joe recalls. “We spent a lot of time in New York, and I saw a lot of jazz. That motivated me to give up my life in the UK and move to the United States.”

On December 16, 1965, Temperley (with his first wife and their son) arrived in New York aboard the Queen Mary. They stayed at the Bryant Hotel, and—after a short stint selling transistor radios at a department store—Joe went to work with Woody Herman’s band. From that point on, he played alongside the greatest musicians of his day: Joe Henderson, Buddy Rich and Clark Terry. Half a century later, it’s hard to name someone he hasn’t played with. “Billie Holiday… Frank Sinatra… Ella Fitzgerald….Barbara Streisand….” Joe squints into the past; the list seems endless.

“Did you ever play with Louis Armstrong?”

“Not with him,” Joe admits. “But in London, we opened for him.”

Temperley’s West Side apartment is small but inviting, decorated with posters from past gigs and framed photos of Temperley with family and friends (including Bill Cosby and Bill Clinton). A Thad Jones score is splayed on a folding music stand, and shelves sag with books on jazz history.

“Music was changing in 1968,” says Joe. “But compared with today, there was a lot of work in New York. Some people did “The Tonight Show, some people did Dick Cavett. There was a lot of recording going on, and every hotel had a band with a cabaret.”

At this point, Joe was working with the Thad Jones and Mel Lewis Jazz Orchestra. “It was, you know, a dream band. We played the Village Vanguard every Monday.” The stream of musicians who sat in were the lifeblood of late 1960s jazz. “Miles Davis came in two or three times. And Charlie Mingus, André Previn, Bill Evans. People from the Ellington band. Monday night was a big social scene, and some marvelous people came down there.”

There were two watersheds in Temperley’s New York career. The first came in 1974, when the Rev. John Gensel—known as “The Shepherd of the Night Flock” for his close ties to the jazz community—asked Joe to play at Harry Carney’s funeral. Carney had blown the baritone sax for Duke Ellington and was one of Joe’s heroes. “My main influence was—and still is—the Duke Ellington Orchestra,” says Joe. “That has always been my prime motivation for playing music, for playing jazz.”

Temperley’s performance gripped the mourners—including Mercer Ellington, who’d taken his late father’s place as band leader (Duke himself had died that May).

“A couple of weeks later, Mercer called me,” says Joe. “And invited me into the Duke Ellington Orchestra.”

Though Temperley left Ellington in 1984, he kept coming back—to tour Japan, and perform for two years in the Broadway run of Sophisticated Ladies. But his second real triumph came in late 1988, when he joined Wynton Marsalis and the newly created Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra.

At rehearsal, I ask Marsalis what makes Temperley so attractive.

“With Joe, there's just the sound—and the integrity in the sound, the originality of it.” Marsalis shakes his head. “When you hear his sound you love him automatically, because it's so full of warmth and soul and feeling. It's like a warm voice.”

“Joe’s sound represents the history of jazz music,” agrees Victor Goines, a tenor sax player who’s been with JLCO nearly as long as Joe. “When you hear him, you hear everyone who came before him. All in one person. He’s someone who's willing to share with everyone else—and at the same time he can always express his own opinion in his own, very unique way.”

“So in a crowded room,” I ask, “would you recognize Joe’s sound?”

“Yes,” Goines answers, unhesitating. “In two notes.”

Though Jazz at Lincoln Center has been Joe’s gig for 23 years, it never gets less challenging.

“Most bands have a repertoire; they play the stuff they're famous for,” says Temperley. “The Ellington Orchestra used to do that. But JLCO plays different concerts every night. And we never know what we're going to play, because Wynton picks out the music at the last minute! When we tour this fall we'll take maybe 100 arrangements with us.”

When I ask if there’s a composer he finds the most challenging, Joe nods rapidly. “Yeah. Wynton Marsalis! He writes wonderful music. And Wynton’s written a lot of long pieces. He wrote The Vitoria Suite, which has about 12 movements, inspired by Basque music and flamenco music. And he's written a jazz symphony, Swing Symphony he calls it, which we premiered in 2010 with the Berlin Philharmonic.”

“Are Wynton’s pieces challenging because of their length or their difficulty?”

“Their length,” Joe says philosophically. “And their difficulty.”

What’s it like, I wonder, to work alongside one of the greatest musical minds in America?

“He a beautiful man. He does a lot of things that a lot of people don't know about. After each concert, there's probably a hundred kids waiting for him. And he talks to them. Not just a couple of them, everybody. Autographs. Pictures. Moms and dads. Then he comes back to the hotel, changes his clothes, jumps in a taxi, and goes out to find somewhere he can play.

“We have a special thing—but everybody has a special thing with Wynton. Everybody he comes in contact with. From the doorman to the president, he's the same with everybody.”

After more than 20 years, the admiration is mutual.

“It's difficult to express in words,” admits the highly expressive Marsalis, “the depth of respect and admiration we have for Joe. And it's not just about music. It's also a personal, a spiritual thing. His approach is timeless. And he's the center of our band.”

Aside from his prowess behind the instrument, Temperley’s physical endurance has become the stuff of legend. Every member of JLCO, including Marsalis himself, expresses awe at his stamina. Marcus Printup, who’s played trumpet with the band for 18 years, sums it up best.

“We're on the road six, seven, maybe eight months per year. So all the guys are complaining, ‘Man, we gotta get up early, we gotta carry our bags, we gotta do this and that.’ And Joe Temperley is walking in front of everyone. We’re in our 20s and 30s, and Joe’s 20 steps ahead of us. He’s the first one on the bus. He’s the first one to the gig. He's always warming up. He's just a real road warrior.”

David Wolf, Joe’s physician for the past ten years explains, “As we grow older, our lung function decreases—but that can happen slowly. What’s remarkable about Joe is that playing the saxophone also requires excellent eye and hand coordination, which often becomes impaired with age. If Joe had a tremor, or arthritis, that would make it very difficult to play the keys.” There’s also vision: reading a complex score, in low stage lighting, can be an effort—not to mention holding a 20-pound instrument hours at a time.

“He's made of stronger stuff than we are,” affirms Sherman Irby. “We all hope we can be like that when we get to his age. If we make it to his age!”

To hear it from Joe, though, performing into his 80s isn’t much of a trick. His career has been an ascending scale, from note to note, with none of the fuzziness or frailty that we mortals associate with the octogenarian years.

I ask Temperley if his ability to play, and improvise, has changed with age.

“Well,” he laughs, “I'm a lot better now than I was 40 years ago!”

“Is anything about the saxophone more difficult for you now?”

“Just carrying it,” Joe shrugs. “The rest is easy.”