Joy Harjo’s New Poetry Collection Brings Native Issues to the Forefront

The recently announced U.S. Poet Laureate melds words and music to resist the myth of Native invisibility

:focal(1000x567:1001x568)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/14/da/14da4bc5-e9fd-44e3-92ea-4903ba3e75f1/gettyimages-52064378.jpg)

Seeing Joy Harjo perform live is a transformational experience. The internationally acclaimed performer and poet of the Muscogee (Mvskoke)/Creek nation transports you by word and by sound into a womb-like environment, echoing a traditional healing ritual. The golden notes of Harjo’s alto saxophone fill the dark corners of a drab university auditorium as the audience breathes in her music.

Born in Tulsa, Oklahoma, Harjo grew up in a home dominated by her violent white stepfather. She first expressed herself through painting before burying herself in books, art and theater as a means of survival; she was kicked out of the home at age 16. Although she never lived on a reservation nor learned her tribal language, at age 19 she officially enrolled in the Muscogee tribe and remains active today. Though she has mixed ancestry, including Muscogee, Cherokee, Irish and French nationalities, Harjo most closely identifies with her Native American ancestry. On June 19, the Library of Congress named her the United States Poet Laureate, the first Native American to hold that position; she’ll officially take on the role next month.

Although English is the only language Harjo spoke growing up, she has a deeply fraught relationship with it, seeing her own mastery of the language as a remnant of American settler efforts to destroy Native identity. Nevertheless, she has spent her career using English in poetic and musical expression, transforming collective indigenous trauma into healing.

“Poetry uses language despite the confines of language, be it the oppressor’s language or any language,” Harjo says. “It is beyond language in essence.”

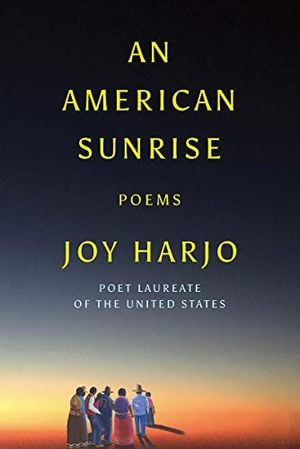

In An American Sunrise, Harjo’s 16th book of poetry, released by Norton this week, she continues to bear witness to the violence encountered by Native Americans in the aftermath of Andrew Jackson’s Indian Removal Act. Her words express that the past, present and future are all part of the same continuous strand.

An American Sunrise: Poems

A stunning new volume from the first Native American Poet Laureate of the United States, informed by her tribal history and connection to the land.

“Everyone’s behavior, or story, affects everyone else,” says Harjo. “I think of each generation in a spiral standing together for healing, and maybe that’s what it comes to. What each of us does makes a wave forward and backwards. We each need to be able to tell our stories and have them honored.”

Kevin Gover, a citizen of the Pawnee Tribe and director of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian first saw Harjo perform with her band Poetic Justice in the mid- to late- ’80s. He says that she, like all great poets, writes from the heart, but she has a special way of capturing the Native American perspective.

“She sees things in a way that is very familiar to other Native people,” he says. “Not in terms of opinion or viewpoint, but just a way of seeing the world. A lot of her metaphors have to do with the natural world and seeing those things the way that we do. She also expresses the pain and the historical trauma that Native people are very familiar with.”

The new poems she shares in An American Sunrise are about all that was stolen—from material possessions to religions, language and culture—and their children whose "hair was cut, their toys and handmade clothes ripped from them." She also speaks to her fellow Native people and offers harsh warnings about losing themselves to the false freedoms of substances, as well as an invitation to stand tall and celebrate their heritage: “And no matter what happens in these times of breaking—/ No matter dictators, the heartless, and liars, / No matter—you are born of those / Who kept ceremonial embers burning in their hands / All through the miles of relentless exile….”

During the late 1960s, when a second wave of the Native American renaissance flourished, Harjo and other Native writers and artists found community in awakening more fully into their identities as indigenous survivors of ethnic cleansing. The only way to make sense of the ancestral trauma was to transform the pain into art that reimagined their narratives apart from white culture.

In the titular poem in her latest collection, Harjo contrasts the land against the bars where Natives "drank to remember to forget." Then they would drive “to the edge of the mountain, with a drum. We / made sense of our beautiful crazed lives under the starry stars.” Together they remembered their sense of belonging to tribal culture and to the land: “We knew we were all related in this story, a little Gin / will clarify the dark and make us all feel like dancing.” The poem ends with the yearning for recognition and respect: "Forty years later and we still want justice. We are still America. We."

Long before Harjo was named poet laureate, placing her oeuvre on a national stage, she encountered challenges with finding her audience in the face of Native American invisibility.

While she did find some positive mentorship at the esteemed Iowa Writer’s Workshop, where she graduated with an MFA, Harjo also experienced isolation at the institution. “I was invisible, or, ghettoized,” she says of her time there. At one point, while performing at a reception for potential donors, she overheard the director say that the program was geared more for teaching male writers. Even though she knew it was true, the bluntness was shocking to hear.

Harjo emerged from the program around the same time as contemporaries Sandra Cisneros and Rita Dove, who collectively became three of the most powerful voices in poetry from their generation.

Later in her career, Harjo introduced a major shift in her performance. At age 40, heavily influenced by the musical sensations of jazz, she learned to play the saxophone as a method of deepening the impact of her spoken word poetry. She also plays Native American flute, ukulele and drums, and she alternates between them for different emotional resonance. “Music is central to poetry and to my experience of poetry,” says Harjo.

Amanda Cobb-Greetham, a scholar of Chickasaw heritage, chair of the University of Oklahoma’s Native American Studies program, and director of the Native Nations Center has read, studied and taught Joy Harjo’s work for more than 20 years. She says that for Harjo, a poem goes beyond the page. “It is sound, rhythm and spirit moving in the world,” she says. “Maybe it is moving the world.”

With five musical albums released between 1997 and 2010, and a thriving performance schedule to this day, Harjo looks back on her earlier, pre-music, works as incomplete. “My performances have gained from musical experiences,” she says. “I’ve listened back to early poetry performances, before my musical experiences with poetry, and I sound flat, almost monotone.”

Harjo’s stage presence carries with it an act of rebellion. She not only holds space for healing the mutilated histories of Native Americans, but also for other indigenous peoples around the world.

Our understanding of intergenerational trauma is now bolstered by emerging scientific research in epigenetics that suggests trauma is not simply an effect of direct experience by an individual, but can be passed through genetic coding. This is perhaps one explanation for Harjo’s emphasis on inhabiting powerful ancestral memories.

“I have seen stories released into conscious memory that have been held previously by ancestors,” she says. “Once I found myself on the battlefield at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend, the definitive battle, or massacre, essentially a last stand against the illegal move. My great-grandfather of seven generations stood with his people against Andrew Jackson. I felt myself as my grandfather. I felt what he felt, smelled and tasted gunpowder and blood. Those memories live literally within us.”

Gover emphasizes that Harjo’s appointment as U.S. Poet Laureate both validates her talent as a poet as well as the Native American experience and worldview. “Those of us who read Native American literature know that there are a number of very fine authors and more coming online all the time. So to see one of them honored as Poet Laureate is very satisfying to those of us who know the quality of Native American literature.”

Ten years ago, Harjo wrote in her tribe’s newspaper, Muscogee Nation : “It’s difficult enough to be human and hard being Indian within a world in which you are viewed either as history, entertainment, or victims….” When asked if she felt the narrative about Native Americans has shifted at all since, she points to the absence of significant political representation: “Indigenous peoples still do not have a place at the table. We are rarely present in national conversations.” Today, cultural appropriation remains rampant in everything from fashion to non-Native people casually calling something their spirit animal.

While she is excited by projects like Reclaiming Native Truth, which aims to empower Natives to counter discrimination and dispel America’s myths and misconceptions about American Indians through education and policy change, Harjo says that under the Trump administration, Native Americans are at a similar crisis point as during the Andrew Jackson era.

“We are concerned once again about our existence as Native nations,” she says. From selling sacred land at Bears Ears National Monument and Grand Staircase-Escalante, to attacks on protestors at Standing Rock, to voter suppression laws that unfairly target Native communities living on reservations–many Native Americans see history repeating itself today.

Additionally, the separation of children from their families at the border mirrors the long history separation of Native children from their families. “What is going on at the border is reminiscent of what happened to Natives during the Removal Era,” says Harjo. Until 1978, when Congress passed the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA), state officials, religious organizations, and adoption agencies routinely practiced child-family separation as part of assimilation efforts, which tore apart and deeply traumatized Native communities

Harjo says that her generation has always been told by elders that one day, those who have stolen from them and ruled over them by gun power, population, and laws will one day come to them to remember who they are for survival. “I do believe these teachings are within indigenous arts, poetry, and performances, but they must be accessed with respect.”

Cobb-Greetham adds, “I know that through her appointment as U.S. Poet Laureate, many others will come to understand her poetry as the gift it is—a gift to be shared, given, and received.”

Harjo’s wisdom teaches that poetry and music are inseparable, and she acknowledges poetry and activism also have a strong kinship. “A poem, a real poem, will stir the heart, break through to make an opening for justice.”

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.