No writer in the English language has ever created a more complete world than John Ronald Reuel Tolkien. Middle-earth, where his famous stories take place, was meant to be a version of our own world in a forgotten past. Tolkien mapped out elaborate geographies and built richly detailed civilizations. Every work of fantasy that came later, from the Harry Potter novels and Star Wars movies to games like Dungeons and Dragons, owes a great debt to Tolkien’s astonishing imagination and pays homage to it.

Tolkien even invented languages for his elves and other characters to speak, drawing on elements of Northern European tongues such as Finnish and Welsh. In his day job, he was an Oxford professor, an esteemed scholar in Anglo-Saxon and related languages and cultures. And yet his lifeblood went into the books that have since almost eclipsed his academic reputation.

He began dreaming up Middle-earth in 1914 as an Oxford undergraduate at the outbreak of World War I, in which he went on to fight as a British Army officer at the Battle of the Somme. He created the mythology to express his “feeling about good, evil, fair, foul,” he said. In 1937, he published the adventure story The Hobbit, and in the 1950s, the epic three-volume The Lord of the Rings. The books enchanted some readers—as Tolkien’s fellow writer C.S. Lewis put it, “Here are beauties which pierce like swords or burn like cold iron.” Others found the books baffling or, as the literary critic Edmund Wilson put it, “juvenile.” By the end of Tolkien’s life, his books were becoming more widely respected for their literary merits and wide-ranging influence. The stories reached a new generation and an even wider audience in 2001, when the director Peter Jackson launched the first installment of his Lord of the Rings movie trilogy. It’s still one of the highest-grossing film series of all time, with nearly $3 billion in revenue worldwide. Its final installment alone earned 11 Academy Awards, matching the records set by Ben-Hur and Titanic.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/b4/c2/b4c21c09-d35b-4c4a-b9ab-a5d0dc5b2c41/oct2022_e09_tolkien.jpg)

Both The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings take place in what Tolkien called the Third Age of Middle-earth, a time when the elves are growing increasingly remote, humans are increasingly dominant, and hobbits—rustic, half-sized humans—emerge as unlikely heroes. Immortal elves such as Galadriel can recall the First and Second Ages, thousands of years in the past, but the full story remained incomplete during Tolkien’s lifetime.

When he died in 1973, Tolkien left behind a mass of papers. His son Christopher compiled and edited his father’s First and Second Age writings as The Silmarillion as well as a magisterial 12-volume History of Middle-earth, showing how Tolkien crafted his world across six decades. Though The Silmarillion is a coherent whole, it is undeniably complex and austere. It takes considerable devotion to read the History of Middle-earth, filled with unfolding variations of tales that were often tantalizingly unfinished.

One Second Age story came out of what Tolkien called his “Atlantis complex.” For as long as he could remember, he had suffered a recurring nightmare of a great wave rolling over green fields. He would awake as if out of deep water, gasping for air. In Quenya, one of the elf languages Tolkien had invented in his youth, the root -lant meant “fall.” In 1936, he built on this root, turning it into a verb— atalantië—which meant “slipping, sliding, falling down.” Suddenly, it struck him that the word he’d just coined sounded like Atlantis, the name of the doomed ocean nation described in Plato’s dialogues. Tolkien’s linguistic notes from 1936 show the eureka moment. He scribbled down an erupting plot idea about an island called Númenor that was drowned by the sea. He hurled the first, brief version of this story, “The Fall of Númenor,” onto paper so fast that Christopher later had trouble deciphering it.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/d4/01/d4015dfa-5870-4145-910b-474ac129a65b/oct2022_e04_tolkien.jpg)

The tale of Númenor begins after the First Age. The primal evil power, Morgoth, has been vanquished by elves and mortal humans with divine aid from the Valar, the angelic guardians of the world. The Valar reward the mortal allies with a new home, the island demi-paradise of Númenor. As the Second Age dawns, the Númenóreans enjoy biblically long lives, with skills and crafts nurtured by the elves. But every Eden has its forbidden fruit. The Númenóreans are barred from sailing west toward the rim of the flat earth, where elves live in Undying Lands alongside the Valar.

Envy of immortality begins to eat away at the mortals of Númenor. A schism leads to persecution of the elf-friends, those who are still true to the elves. Eventually, Númenor’s king comes under the insidious influence of Sauron, who had once been Morgoth’s second in command. At Sauron’s encouragement, the Númenóreans build a temple to Morgoth and launch an armada against the Undying Lands.

An act of God opens an ocean rift that engulfs the island. In the same stroke, the world, hitherto a flat disk, is refashioned as a globe, and the Undying Lands are removed to a mystic dimension of their own. The few remaining elf-friends sail on the wings of storm to mainland Middle-earth to begin life—and the war against Sauron—anew. Flashback revelations in The Lord of the Rings pick up the story from here.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/5c/7a/5c7aa912-20c3-4ad3-9970-e28c5083d7a7/oct2022_e07_tolkien.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/44/61/44612673-7598-49db-b18a-72fa68870c15/oct2022_e12_tolkien.jpg)

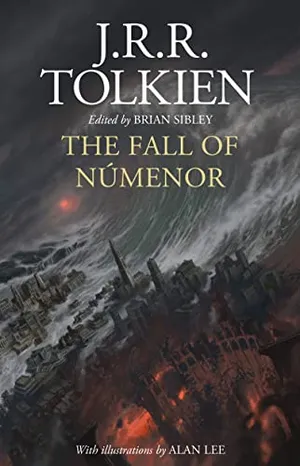

Right now, Tolkien’s lost Second Age history is finally reaching a wider audience. Amazon Studios is launching a multi-season series called The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power with a budget of more than $1 billion, hoping to reignite the enthusiastic response to The Lord of the Rings movies. Meanwhile, a book, The Fall of Númenor, to be published in November, will gather all of Tolkien’s writings about the Second Age into one volume.

To recreate Tolkien’s lost island, the show’s creators, J.D. Payne and Patrick McKay, gathered inspiration from real-world historical cultures. Tolkien himself used a similar approach—for instance, the rural village where The Hobbit begins resembles the author’s childhood village as it was in 1897. In The Lord of the Rings series, the hobbits journey to Rohan, a kingdom that feels more remote, with a language and a royal hall evocative of Anglo-Saxon England, and then onto the kingdom of Gondor, which owes something to Rome or Byzantium.

Amazon’s Payne and McKay drew on some of these same civilizations, as well as on Moroccan, Babylonian and Indian sources. “Our hope is that it comes together in something that feels real and discovered,” McKay said in an email, “but also like something you’ve never seen before; in short, our hope is that it feels like Middle-earth.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/bf/6b/bf6bc757-195d-4b41-90fd-30a48c6d19a0/oct2022_e16_tolkien.jpg)

One does not have to spot the allusions in order to feel the power of these stories. Nor should we imagine that Tolkien built his worlds from a rigid system of references. The author fused his inspirations into an alloy that he could shape freely. He also generated multiple stories from a single inspiration. What he called his “feigned history” lives on its own terms. But by pinpointing his sources, we can learn more about what moved the 20th century’s most influential world-builder. What were Tolkien’s immediate inspirations for the Second Age of Middle-earth?

I had my own eureka moment when I noticed an unobtrusive comment by Tolkien that the Númenor idea had come while he was writing the jacket blurb for the forthcoming Hobbit. Other evidence shows he wrote that blurb between December 5 and 8, 1936. Describing the book’s setting for prospective readers, Tolkien wrote, “The period is the ancient time between the age of Faerie and the dominion of men.” The Númenor story would bridge those two epochs, explaining what happened between the defeat of mighty Morgoth in The Silmarillion and the rise of little Bilbo Baggins in The Hobbit.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/9a/87/9a87ab4c-df02-498f-ae46-67bf9ea3b189/untitled-1.jpg)

This practical need, however, explains neither the Númenor story’s eruptive birth nor its sheer anguish and rage at human folly. The end of 1936 does.

The year 1936 was, as one British newspaper put it, “desperately charged with fate...which seemed to bring catastrophe near.” The 1918 Armistice had brought no idyll, yet at least there had been a chance to heal the hurts of war. But now Mussolini’s fascist Italy had bombed and gassed Ethiopia into subjection. Hitler’s troops had reoccupied the demilitarized German Rhineland. Stalin’s Soviet purges had begun. Spain had exploded into a civil war that split opinion internationally and seemed bound to result in dictatorship by left or right.

Even Britain was riven with unrest. Ominously, on November 30, the Crystal Palace, a vast glass structure built as a showcase for Victorian optimism and imperial splendor, had gone up in flames. Over the next two days, the east coast suffered heavy storms and severe flooding. Then, on December 3, newspapers confirmed a long-suppressed rumor that the new king, Edward VIII, wanted to change the royal marriage rules so he could marry a divorcée, the American Wallis Simpson.

The abdication crisis was transfixing the nation during the week Tolkien was writing the Hobbit blurb. On December 10, Edward surrendered the crown to his brother, George VI. The change in socially hidebound Britain was seismic. As Virginia Woolf declared, “Things—empires—hierarchies—moralities—will never be the same again.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/a6/d4/a6d40fd5-7600-4071-846c-119493b3b7c1/oct2022_e01_tolkien.jpg)

Tolkien’s Catholicism surely colored his view of Edward. The leading British Catholic journal The Tablet pointed out that the last king to seek to alter the royal rules relating to divorce had been Henry VIII. Henry’s dire solution had been to sever England from the Roman church, create a new Church of England with himself at its head, and treat Catholics as enemies of the state.

There are striking parallels between Henry VIII and Númenor’s king, Tar-Calion (better known to Tolkien fans under a name coined later, Ar-Pharazôn). In Tolkien’s story “The Lost Road,” Tar-Calion decrees himself “Lord of the West.” But only the chief of the Valar—God’s archangelic representative in the mortal world—is supposed to bear that title. It is the Middle-earth equivalent of Henry claiming to be head of the church in place of the pope.

Did Tudor England truly interest Tolkien, a dyed-in-the-wool medievalist? Yes, it did—and at this very point in his life. In 1935 he had read, twice in quick succession, a biography of the Renaissance humanist Thomas More, written by his friend R.W. Chambers. More, a counselor to Henry VIII, and lord chancellor for three years from 1529, had refused to recognize the new Church of England or Henry as its leader. More was beheaded for high treason in 1535 and canonized by Pope Pius XI in 1935. Although Chambers himself wasn’t Catholic, he argued that English Catholicism had been expunged by a cynical tyrant to enrich and empower himself, and that much that had been good about the Middle Ages was thereby forever lost.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/44/f4/44f4b441-f3aa-48cb-98b0-71554904e3c7/oct2022_e15_tolkien.jpg)

Tolkien told Chambers that his biography was “overwhelmingly moving: one of the great sagas.” Among various subtle signs of More’s impact on the Hobbit author, around this time Tolkien used the pen name “Oxymore,” which is (besides other things) a portmanteau of “Oxford” and “More.”

More’s seminal 1516 treatise, Utopia, described an ideal island society, and Númenor itself starts out as an island utopia. Knowing More’s impact on Tolkien, we can also see that he is a likely inspiration for the father of the Númenórean hero Elendil. In “The Lost Road,” Elendil’s father mirrors More’s acutely difficult position as friend and counselor to an apostate king. Like his father, Elendil (whose name means “Elf-friend”) is one of the faithful Númenóreans who still revere the angelic Valar in the west and the one God who is above all. He clearly sees the evils brought by Sauron while others see only progress.

In Tudor times, the printing of vernacular Bibles dethroned Latin as the language of Christian faith. In Númenor, too, language is a battleground, with Quenya—which Tolkien called “Elf-latin”—being driven underground in favor of a human language.

Tolkien said he found the Thomas More biography “almost burningly topical” when he read it in the mid-1930s. The book did not need to spell out specific parallels to Nazi Germany. In the 1930s they were visible to all who had eyes. Chips Channon, an American-born member of the British Parliament, wrote in his diary that King Edward VIII was “going the dictator way, and is pro-German.” The week of the abdication crisis raised anxieties that a “King’s Party,” led by Winston Churchill (as yet a divisive figure) and supported by fascist leader Sir Oswald Mosley, would emerge and bring civil strife.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/31/50/315029f0-00dc-4dac-acc0-c15a631a34a0/oct2022_e02_tolkien.jpg)

In Númenor, such events do come to pass. “The Lost Road” is a time-travel story in which, via dream, 20th-century observers witness Númenor’s fall. Tolkien’s anger feels live and burning. Christopher Tolkien later said, “When at this time my father reached back to the world of the first man to bear the name ‘Elf-friend’ he found there an image of what he most condemned and feared in his own.”

Elendil catalogs the rabid construction of arms and warships, whispered denunciations, disappearances, torture behind closed doors. He blames Númenor’s evils squarely on Sauron. In The Silmarillion, Sauron had been a shape-shifting lord of werewolves, quite different from the sinister manipulator who emerges in “The Lost Road.” Even some of the details are reminiscent of Hitler’s policies. In a mirror-image of Nazi demands for Lebensraum (living space), Sauron’s acolytes in Númenor want “to conquer new realms for our race, and ease the pressure of this peopled island.”

Later, Tolkien would declare a “burning private grudge...against that ruddy little ignoramus Hitler” who had hijacked Tolkien’s beloved Northern European mythology for propaganda purposes. Likewise, Sauron twists the story of why Númenor’s national forefather, Eärendil, sailed to the Undying Lands at the end of the First Age: Eärendil had actually made the journey to beg the Valar’s aid against Morgoth, but in Sauron’s revisionist version, he’d gone to seize unending life for himself. The colossal temple to Morgoth even strikingly parallels the plans laid by Hitler’s architect, Albert Speer, for a Volkshalle (people’s hall).

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/eb/0b/eb0b104d-49c7-417d-b754-24a7db6c38cb/oct2022_e03_tolkien.jpg)

By 1936, Tolkien was well acquainted with tragedy. After his mother died when he was 12, Tolkien had felt “like a lost survivor into a new alien world after the real world has passed away.” He felt the same in 1935 on the death of his guardian, Father Francis Morgan, the man he called his “second father.”

When the news of the abdication broke on December 3, 1936, it had been 20 years to the day since Tolkien’s friend Geoffrey Bache Smith died in France, the keenest of many griefs from the Great War. Now, Tolkien’s son Christopher had just turned 12, Michael was 16, and John 19. When Tolkien himself had been that age, the Great War had been just three years ahead—and the omens now were far worse.

Tolkien abandoned “The Lost Road” in 1937 when The Hobbit’s publishers demanded the sequel that eventually became The Lord of the Rings. But Tolkien returned to work on Númenor just after the Second World War. A new story—also sadly unfinished—involved a clique of Oxford dons very much like the Inklings, a group of literary friends Tolkien shared with C.S. Lewis. Memorably, one of Tolkien’s fictional 20th-century academics has a vision of the Radcliffe Camera—part of Oxford’s great Bodleian Library—as the temple of Morgoth, with the smoke of human sacrifice pouring from its louvers. The enemy is now at the heart of the realm: The story reads like an aftertaste of the invasion fear that Britons had endured in the intervening years.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/37/e1/37e1780f-bdcb-4885-9c25-240578c70102/oct2022_e11_tolkien.jpg)

Meanwhile, Tolkien continued developing the vast history of his fictional world. After Númenor’s destruction, Elendil leads the faithful to safety and establishes, with his sons, the twin kingdoms of Arnor and Gondor. From a high hilltop tower—surely inspired by one at Faringdon near Oxford built in 1935—he gazes out over the seas toward the lost world that had been Númenor. In the Third Age, Aragorn, the hobbits’ wandering companion and king-to-be (played by Viggo Mortensen in the films), will be Elendil’s direct descendant and heir.

Looking at the evidence, it is clear that Hitler and other 1930s despots were very relevant to Tolkien’s Númenor stories and his all-important equation of Sauron with tyranny. Yet Tolkien officially denied that The Lord of the Rings was an allegorical code for the Second World War. How do we square this circle?

In the foreword to the 1966 edition of The Fellowship of the Ring, the first book in the trilogy, Tolkien wrote, “I cordially dislike allegory in all its manifestations, and always have done so since I grew old and wary enough to detect its presence. I much prefer history, true or feigned, with its varied applicability to the thought and experience of readers. I think that many confuse ‘applicability’ with ‘allegory’; but the one resides in the freedom of the reader, and the other in the purposed domination of the author.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/c1/e1/c1e18caf-6638-4268-acc4-56746ab4779e/oct2022_e17_tolkien.jpg)

In other words, in this book about tyranny, Tolkien was loath to act like a dictator by telling his readers what to think. He built his world out of the worlds he knew. But he would have hoped that in future times, with other dictators, his work should continue to feel relevant.

In this, he has succeeded. As Amazon Studios’ senior development executive Kevin Jarzynski says, Tolkien’s work is not “about one specific moment in time but a repetition of history. There are some lessons that we as a people are always trying to learn about power, about temptation, time and time again.” The key message of Númenor, as timely now as ever, is that the lust for power leads to wholly avoidable disaster.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

:focal(3170x2113:3171x2114)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/7b/1c/7b1c29dd-d650-45e9-97dd-ecc30e5c3246/oct2022_e05_tolkien.jpg)