Keeping the Blues Alive

Is blues music a thing of the past? A festival in Memphis featuring musicians of all ages and nationalities shouts an upbeat answer

:focal(957x1171:958x1172)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/81/8f/818fade4-1a10-4d60-a3a6-9f5df39b7e95/sep2016_i01_blues.jpg)

It’s a Friday afternoon in Memphis and we’re in the midst of the 32nd annual International Blues Challenge, at a barbecue joint on the legendary Beale Street, where 150 people are waiting for a musician named Redd Velvet. I have been told she’ll be worth the wait, that there may be nothing more important onstage this week. So I’m there when this 40-something black woman walks onstage with a no-frills blue dress and an unmistakably regal bearing. There’s no band behind her. No instrument in her hands. It’s just her and a mike. She sits. Folks in the audience are still chatting, there’s a small din, so Redd looks around the room with piercing eyes, letting you know she’s not talking until it’s quiet. The flock who came to see her says, “Shhh!” The crowd settles down. With that Redd has set a high bar for herself—if you demand everyone to shut up before you start talking, you’d better have something to say.

“The blues is an antipsychotic to keep my people from losing their minds,” she begins. “It started with the moans and groans of agony, the slave roots of it all.” Then she sings, “There’s a man goin’ ’round takin’ names! There’s a man goin’ ’round takin’ names!” She shoots us a coldblooded look. “Even their simplest songs were coded communications such that we could have a conversation and the master would never be the wiser.” Those messages didn’t stop after Emancipation. She croons the chorus of Jimmy Reed’s classic “Big Boss Man”: “Big boss man, can’t you hear me when I call? / You ain’t so big, you just tall, that’s just about all.” Redd goes on: “If Jimmy Reed had said to his boss, ‘I won’t put up with this, I’m through,’ he would’ve been dead before dark. Jimmy Reed got people to buy a record where he’s saying something he woulda gotten killed for saying in real life. That means the blues is some bad stuff!”

I get it. The whole room has got it now. It’s church and theater and history and testifying all at once. And Redd has us in the palm of her hand.

There’s no question that Americans revere the blues. Its story is being enshrined in careful, loving ways at the National Blues Museum in St. Louis and the Grammy Museum Mississippi, both of which opened this spring. The mere existence of these two institutions, though, raises the question of whether the blues are now just a thing of the past. “Both personally and professionally I’m fearful that the blues will wind up a historic music form, much like Dixieland and big-band music,” says Robert Santelli, the executive director of the Grammy Museum and the author of several books about the blues, including The Best of the Blues: The 101 Essential Albums. “It’s not that the blues is dying. There’s just such a small minority who embrace it in a way that will allow the form to grow and prosper in the 21st century. It’s not a music form that has an easy and bright future in 21st-century America.”

Tonight on Beale Street the blues is very much alive. The street buzzes with music from every direction, and fans jump between bars with names like the Rum Boogie Cafe, Wet Willie’s and Miss Polly’s Soul City Cafe. There’s gumbo, fried chicken, ribs and cold beer everywhere. And right now in almost every spot on Beale Street there’s a stage filled with bluesmen and women doing their thing. Over 200 acts have flown in from around the world to compete for prize packages that include cash, studio time, and a slew of gigs including the Legendary Rhythm and Blues Big Easy Cruise, the Daytona Blues Festival, the Hot Springs Blues Festival, Alonzo’s Memorial Day Picnic and more. These are potentially game-changing prizes for small acts. It’s a serious competition.

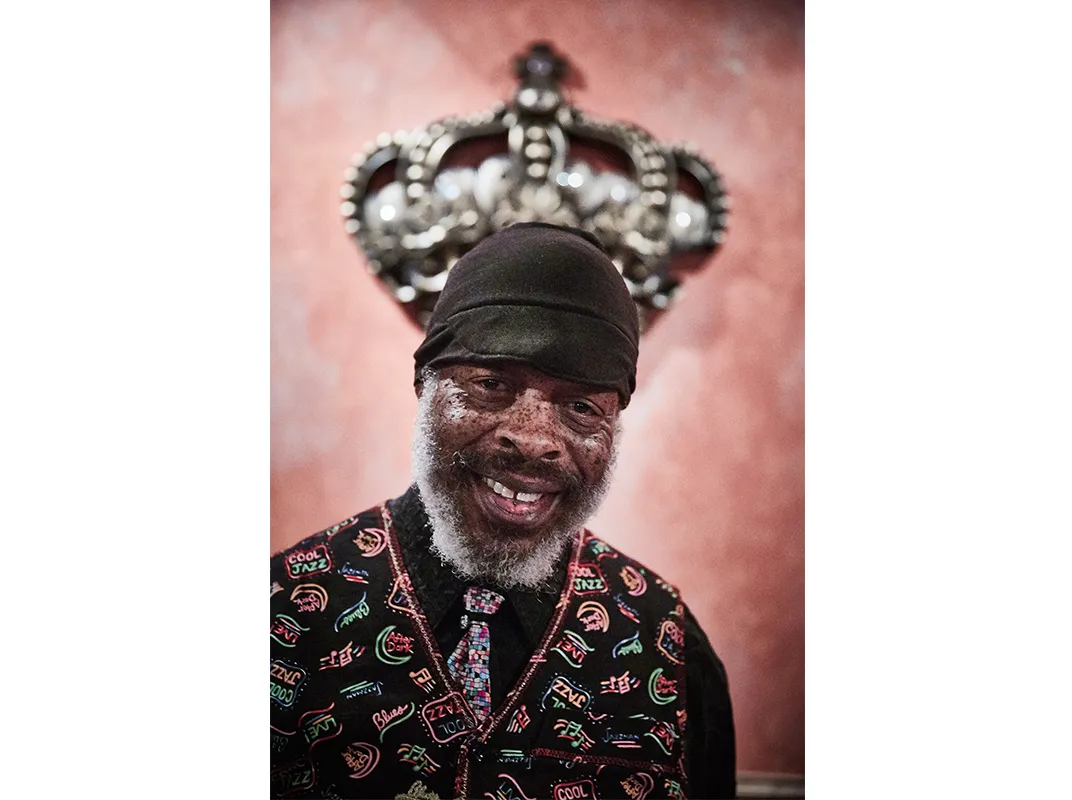

One night, around 11, I watch my eighth act of the evening—Roharpo the Bluesman, an older black man with long curly hair, a loose-fitting tan suit, a black T-shirt and a fedora. He’s from a Baton Rouge family of gospel and blues musicians, and he’s got a big voice and the bluesman’s weary-but-still-keepin’-on-keepin’-on look. He stalks the stage, taking his time, working his way through an energetic “The Blues Is My Business,” while sweating and roaring.

“The blues is spiritual to me,” Roharpo tells me on the sidewalk afterward, peering at me through his rimless glasses. “It’s supposed to deal with one’s inner self. As the bluesman has experienced certain things, he must be able to display that out to the next individual. And that individual should be able to feel what the bluesman is throwing back at him. You say, I know about that. I’ve been there.”

**********

From the beginning, the blues merged the sounds of enslaved people with the sounds of their oppressors. “The blues is born out of the a cappella music of Africa and the music that blacks created as slaves, which manifested as field hollers, mixed together with the European folk music they learned from the slave owners,” says Bing Futch, who won the solo/duo guitar category in the 2016 International Blues Challenge, “as well as some of the music that was coming out at that time.”

As a music form, the blues has certain distinct features. The melody usually goes up and down a six-note scale. (If you’re starting on a C, that scale would go C, E flat, F, G flat, G, B flat, C.) The lyrics tend to follow what’s known as an AAB pattern, with the first line of each verse repeating itself: “The thrill is gone, the thrill is gone away / The thrill is gone, the thrill is gone away.” The “B” line usually answers or resolves whatever is in the “A” line: “You know you done me wrong, baby, and you’ll be sorry someday.”

The blues also evokes a particular response in the listener, says Susan Rogers, an associate professor at the Berklee College of Music: “Rock arouses and pumps up; it is intense and rebellious. R&B soothes and often seduces; its lyrics tend to be externally focused. Blues is more introspective and complex; its lyrics tend toward describing one’s internal state.”

During the 20th century, this melancholy music was the sound of the rural South. “The blues came out of the life of struggle,” says Barbara Newman, the president and CEO of the Blues Foundation, a nonprofit that serves as an umbrella for more than 175 blues organizations around the world. “It came out of what was going on in the Delta, whether it was weather or slavery and sharecropper lives that were difficult.” The emancipated slaves who created it were known as “songsters”: traveling musicians who played standards and new songs. Their music found its way into juke joints—black-operated establishments in the Southeast United States. (The word joog means rowdy in Gullah, the creole of lowland South Carolina and Georgia.) Legends like Jelly Roll Morton, Ma Rainey and W.C. Handy all reported hearing the music for the first time around 1902.

The word “blues” first appeared on sheet music in 1908, with the publication of “I Got the Blues.” The composer, ironically, was a Sicilian-born barber—he later told an interviewer that he came up with the song after wandering the levee in New Orleans and hearing “an elderly Negro with a guitar playing three notes.” In 1920, Mamie Smith made the genre’s first vocal recording, a piece called “Crazy Blues.” It sold over a million copies in its first year. During the 1930s and ’40s, the folklorist Alan Lomax traveled through the Mississippi Delta, interviewing and recording blues players wherever he could find them, from churches to prisons. Many of these musicians never made another recording. Some, including Lead Belly and Muddy Waters, went on to have huge careers.

While the music business was eager to sell so-called “race records,” the motivation for many artists and listeners was the need to transcend very difficult lives. Think of “(What Did I Do to Be So) Black and Blue,” composed in 1929 by Fats Waller and made famous by Louis Armstrong, and, of course, Billie Holiday’s haunting 1939 song about lynching, “Strange Fruit.” “This is music made by any means necessary,” says Matt Marshall, the publisher of American Blues Scene magazine. “Guys often talked about making their first guitar out of baling wire from the side of their house. Talk about needing to get the music out of you! Imagine taking part of the small place where you live and making it into your instrument!”

By the 1950s, Southern oppression was pushing millions of blacks to leave and move to New York, Chicago, St. Louis and other major cities. As black America became more urban, the music changed. For many, it became about electric blues, the sort of music made by Howlin’ Wolf, Muddy Waters and Jimmy Reed, all Mississippians who moved to Chicago during the Great Migration.

Around this time the songs became tamer. Racially charged songs like “Strange Fruit” largely disappeared, as did the racy lyrics. “There were tons of sexual double-entendre songs that came out in the ’30s and ’40s,” says Brett Bonner, the editor of Living Blues magazine. “Those were sung by African-Americans for African-American audiences. For the most part they were thinly veiled but you can find some really filthy stuff—Bull Moose Jackson’s ‘Big Ten Inch Record.’ Or ‘Let Me Play With Your Poodle’ by Tampa Red. A lot of that faded away as the industry became more and more aware of a white audience.”

The audience was, in fact, becoming whiter. During the civil rights era, music executives started using the term “rhythm & blues” to market “race records” to more Northern, urban, upwardly mobile blacks. Before long, black record-buyers were leaving classic blues behind and moving on to the soul music of Motown and the funk of James Brown. A group of white baby boomers took over as the blues’ core audience.

Some of these fans were musicians themselves, and they turned the stripped-down music into arena rock, complete with extended guitar solos. This raised new questions: When Led Zeppelin sings “Babe I’m Gonna Leave You” or Jack White plays a resonator guitar, can it be called the blues? “Everyone draws their own lines on this,” says Bonner. “And in truth they are all fairly fuzzy. For me it all loops back around to the artist’s ties, or lack of ties, to the culture that created the musical form.” In fact, when Living Blues founders Jim O’Neal and Amy van Singel launched the magazine in 1970, they wrote this into the editorial policy: “The blues by definition was and always will be black American working-class music.” (Like Bonner, O’Neal and van Singel are white.)

At the same time, Bonner notes that some black artists play up their working-class connections in order to impress white audiences. “Albert King used to wear a three-piece suit when he played,” Bonner says. “By the time we got to the 1990s, Albert King showed up in bib overalls. He knew what people wanted to see and what their image of the blues was. It was a guy who had strolled in out of the fields.” That rural blues culture has not existed for quite some time. “People still do blues tourism looking for that life, that guy on the front porch, picking cotton, coming home and picking up his acoustic guitar. But nowadays in the Delta that guy riding around in the field, he’s got a GPS.”

**********

Part of what once made the blues so powerful was its response to racism. Players sang about oppression and marginalization, giving black people a space to deal with their pain. This was a core part of what the blues did for its listeners, too—it was meant to heal. In many ways, Americans in the post-Obama age are living lives that are very different from the ones our grandparents had in the Jim Crow South. But songs like “Strange Fruit” still resonate when we hear about black civilians killed by police.

There’s also the question of who gets the credit, and the money, when white performers make blues their own. “The way I see it,” says James McBride, the musician and journalist who wrote the memoir The Color of Water, “the influence of African-American music has been so strong in American society. But the musicians themselves who created it have suffered and died in anonymity.”

In my experience, though, white blues musicians and scholars tend to be aware of these racial politics and acknowledge the music’s history. The Rolling Stones may incorporate blues influences, but they talk endlessly about the artists who inspired them. Jack White made a generous donation to create an interactive exhibit at the National Blues Museum in St. Louis. You can see the same sense of passion and mission among the folks who organized festivals like the International Blues Challenge and the Chicago Blues Festival.

Perhaps the musician most associated with the blues nowadays is Gary Clark Jr., a 32-year-old singer and guitarist from Austin, Texas. I saw him onstage last summer in Brooklyn at the AfroPunk Fest as the sun was dipping down in the sky. He’s got a powerful onstage aura, and his electrified blues was like a transporter to another time and space. “When I’m performing,” Clark told me later, “I’m just trying to reach that other level where you’re kind of just levitating and you disappear for a minute.” The music was raw, soulful, muscular and hypnotic. It incorporated elements of rock, funk, and neo-soul, but it followed the traditional six-note scale, with classic bluesy lyrics about waking up hung over on a New York sidewalk, or falling “in love with a woman who’s in love with a man that I can’t be.”

Clark, who is African-American, got his start playing with Jimmie Vaughan, one of two white brothers who helped redefine the blues during the 1980s. (The other one, Stevie Ray Vaughan, died in a helicopter crash in 1990.) His big break came in 2010 when Eric Clapton invited him to play at the Crossroads Guitar Festival. Clark has since played with artists as wide-ranging as Alicia Keys and the Foo Fighters.

The truth is, if the blues is going to carry into the next generation, the genre has to be open to musicians from all backgrounds. “Right now Alligator Records is essentially a break-even proposition,” said Bruce Iglauer, who founded the blues-based label 45 years ago. “We can survive at our present level, but growth is very hard. I have to fill out all this paperwork so we can get microscopic payments from yet another streaming service.” Iglauer says the 2015 death of B.B. King—the genre’s most recognizable player—left the blues without a face. It’s unclear who will take his place. “With his death I think we’ve entered into a new era.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/21/21/21218aa7-503a-4e84-9454-ec7f280c5e47/sep2016_i06_blues.jpg)

Older blues musicians are eagerly grooming young artists. At the International Blues Challenge, I met Radka Kasparcova, a white 18-year-old guitarist with long blond hair. She told me she was at a Buddy Guy show in her native Philadelphia area in 2014 when Guy asked if anyone in the crowd could play the guitar. She raised her hand high. “He was like, ‘Oh yeah? Show me,’” she said. “I went up on stage with him!” They played three songs together. “It was amazing! There is so much sound and emotion on the stage.” She says that’s the day she really learned how to play. “I started listening differently,” she told me. “Basically, when I played music before I was just playing notes, but when you’re playing the blues, you have to really feel it.”

I also met Grace Kuch, a 12-year-old singer and guitarist whose parents drove from Colorado to Memphis so she could perform at the blues challenge. Kuch was the youngest player at the National Women in Blues showcase, a little white girl who stood sweetly onstage in front of her band. Even though she’s too young to know the rough edges of life that the blues describes, she’s obviously in love with the music. Her mom told me about the time they drove to the Pinetop Perkins Foundation Workshop in Clarksdale, Mississippi—hallowed ground in blues circles. Grace fell asleep on the way there. When she awoke in Clarksdale, she sat up and said, “I feel like I’ve been here before.” She swears that she really did experience a deep sense of déjà vu, almost as if she’d spent a past life in Clarksdale.

Looking around the International Blues Challenge, it’s clear that this music now belongs to the world. One of the first performers I saw there was Idan Shneor from Tel Aviv. He took the stage alone—a tall, lanky, 20-something white boy who resembled a young Ben Affleck. As he sat on a stool, strumming an acoustic guitar, he didn’t seem snakebitten the way bluesmen are supposed to, but his voice was soulful and an extended solo showed off his guitar skills. “All my life I am playing guitar,” he said later, in broken English that had been tucked away while he sang. “And my real soul is always in the blues.” Here on Beale Street, he’d found his tribe. “It feels like home being here,” he says. “The blues is everywhere.”

An hour later, I saw a Filipino blues band called Lampano Alley, led by the 40-something Ray “Binky” Lampano Jr. He was thin, smooth and cool as hell, wearing a porkpie hat and a black suit with a Nehru jacket and red buttons, and carrying a blue cane. He had the sound of B.B. King in his throat and the spirit of the blues in his soul and all the little details of performing it at his fingertips. I watched him onstage in front of 100 people, shouting, “I just want to make...love to you!”

“It’s a life force,” he told me outside afterward, leaning on his cane, speechifying for the small crowd that was gathering around to listen. “Doesn’t matter where it comes from! Doesn’t matter if it came from America or if it came from Europe or Mother Africa or anywhere. If it gets you in the heart, and you let that story move you to the beat, then, man...you’ve got it.” The crowd gave a little cheer.

That life force has always defined the blues, and today’s best players are still able to tap into it. “I think we’re in a day and age where people are performing for the comment section and not performing in that moment,” Clark says. “You gotta be in the moment with the audience and with the band, and you gotta hit every single note with passion and conviction and not worry about making a mistake, or what someone’s going to say if you don’t do something. If you just bring it full on and let everything go, I think that’ll resonate with people. You have to be in it for what it is and not what’s going to be said after the fact. You can’t perform the blues. You got to feel the blues.”

Related Reads

Escaping the Delta: Robert Johnson and the Invention of the Blues