Keeping Up with Mark Twain

Berkeley researchers toil to stay abreast of Samuel Clemens’ enormous literary output, which appears to continue unabated

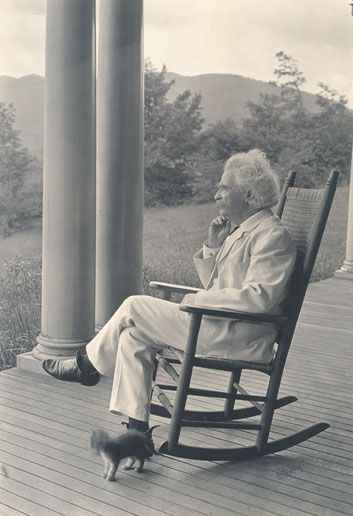

Ninety-three years after his death in 1910, Samuel Langhorne Clemens has been making some ambitious career moves. It’s almost as though the old sage of the Mississippi, better known as Mark Twain, is trying to reposition himself as the King, as friends and colleagues called him long years before Elvis was even born.

In July, an American Sign Language adaptation of the 1985 musical Big River, based on Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and featuring deaf and hearing actors, opened in New York City to enthusiastic reviews. A recently rediscovered three-act play by Twain, Is He Dead? (written in 1898), will be published next month and has been optioned by a Broadway producer. In 2001, the Atlantic Monthly published a “new” Twain short story, “A Murder, a Mystery and a Marriage,” which he’d submitted to the magazine 125 years earlier. He was the subject of a Ken Burns documentary on PBS last year. And the venerable Oxford University Press issued a 29-volume edition of Twain’s published writings in 1996. New biographies and works of critical scholarship are in the works.

In fact, if this new rush of celebrityhood grows any more intense, Mark Twain may want to eat the words he aimed at another overexposed immortal. “Even popularity can be overdone,” he groused in the novel Pudd’n headWilson. “In Rome, along at first, you are full of regrets that Michelangelo died; but by and by you only regret that you didn’t see him do it.”

Of Twain’s many fans, who are apparently growing in number, none could feel more pleased—or more vindicated—by the renewed interest than the steadfast editors of the Mark Twain Project at the University of California at Berkeley, who have been at work for 36 years on a scholarly undertaking of almost inconceivable proportions: to hunt down, organize and interpret every known or knowable scrap of writing that issued from Sam Clemens during his astonishingly crowded 74 years on earth.The University of California Press has so far produced more than two dozen volumes of the project’s labors, totaling some 15,000 pages, including new editions of Twain’s novels, travel books, short stories, sketches and, perhaps most significantly, his letters.

What distinguishes the works is the small print—the annotations. The information contained in these deceptively gray-looking footnotes ranks with the most distinguished scholarship ever applied to a literary figure. Amounting almost to a “shadow” biography of Twain, the project has been an indispensable resource for Twain scholars since the 1960s.

But esteem does not always spell security. If the project’s editors are feeling happy these days, it is only now, after nearly four decades, that their project is emerging from obscurity, even on their host campus, after a virtually unrelieved funding crisis. Mark Twain, of course, would be sympathetic. “The lack of money is the root of all evil,” he liked to remind people; and as for approbation, “It is human to like to be praised; one can even notice it in the French.”

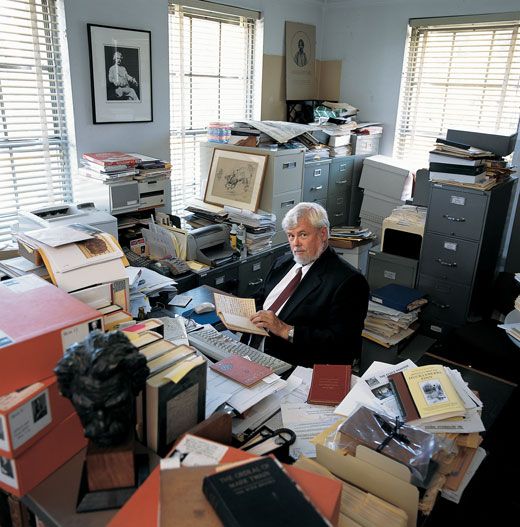

the animating force behind the project, its untiring ambassador and conceptual mastermind, can usually be found at his desk in the project’s newly refurbished and expanded quarters on the fourth floor of the Bancroft Library on the Berkeley campus. This is Robert Hirst, an engagingly boyish figure, despite his 62 years, his thatch of white hair and his sometimes florid coloring (he’s excitable and sharpwitted, not unlike Twain himself). Often the white hair is the only visible part of Hirst; the rest is obscured by stacks of Twainian treasure: manuscript-crammed filing cabinets, shelves of peeling volumes, piled papers and manila folders that threaten to cascade into literary landslides. “No Tiffany wallpaper yet,” Hirst says wryly of the renovation this past June, which increased the office space by three rooms. (The reference is to the walls of Twain’s lavish house in Hartford, Connecticut.) “But we’re painting and redecorating. Straightening the pictures on the walls.

Hirst is sixth in a line of distinguished scholars to supervise the Twain archives—a line that begins with the author’s official biographer, Albert Bigelow Paine, before Clemens’ death and continues with Bernard DeVoto, Dixon Wecter, Henry Nash Smith and Frederick Anderson. Hirst, after studying literature at Harvard and Berkeley, joined the project in 1967 as a fact checker and proofreader, one of many young graduate students hired to do the grunt work for the professors issuing the Twain volumes produced by the University of California Press. Hirst expected to stay only a year or two. Suddenly it was 1980. By then, deeply invested in the project’s goals and methods, Hirst signed on as the project’s general editor. Aside from a few years teaching at UCLA, he has never done anything else. He probably knows more about Mark Twain than anyone alive—perhaps even more than the dreamy author knew about himself.

Beneath Hirst’s warmth and whimsical humor, beneath even the laser intensity and the steely will that underlie his surface charm, one can detect a glimpse, now and then, of a puzzled young man from Hastings-on-Hudson, New York, wondering where all the time has gone. The answer is that it has gone toward carrying out his assignment, even if the task proves to exceed Hirst’s allotted time on earth, as it almost certainly will.

Hirst loves facts and the unexpected illumination that can burst forth from facts scrupulously extracted, arranged and analyzed. “I especially love the ways in which the careful, comparative readings among his documents help us discover new truths that had not been obvious in Twain or his work,” he says.

One such discovery is detailed at length in the California Press’ 2001 edition of Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. A longstanding myth surrounding this founding work of vernacular American literature was that Twain, having discovered Huck’s natural voice, was suddenly “liberated” from the cerebral, piecemeal rhythms of composition, and wrote in long dreamlike bursts of uninterrupted dialect. The highest example of this “charmed” writing was Chapter 19, Huck’s beautiful and lyrically flowing description of a sunrise on the Mississippi. (“Then the river softened up, away off, and warn’t black any more, but gray; you could see little dark spots drifting along, ever so far away...then the nice breeze springs up, and comes fanning you from over there, so cool and fresh, and sweet to smell.”) But as the project editors studied the handwritten draft of the chapter—part of the recently recovered first half of Twain’s original manuscript—and compared it with the first edition, it became obvious that no such dream state ever enveloped Twain. He wrote the passage the old-fashioned way: by patient trial and error, with an obviously conscious awareness of technique. In other words, Twain was not a kind of idiot savant, as some earlier scholars patronizingly supposed, but a disciplined professional writer with sophisticated skills.

It does not entirely gladden Hirst that the 20-plus full and partial biographies of Twain have tended to be infected by what he calls “hobbyhorses”—the biographers’ pet theories, academic arguments and armchair psychoanalyses. (To be fair about it, Mark Twain virtually begs for psychological scrutiny, with his famous bouts of guilt and sorrow, his themes of dual and sham identities, his self-destructive investment binges and his late-life vision of man as machine.) “All these ideas about him, these theories—they need always to be tested against the stubborn facts of the documents,” Hirst says. “That alone—and it is a process that can only happen over a period of years—will increase our understanding of what he was like.”

Under Hirst, the project has grown into a protean resource for those who would dismount the hobbyhorses and follow the facts wherever they lead. Called “magisterial” and “an immense national treasure” by some scholars, the project has produced new techniques in textual analysis and in the capacity to depict multiple revisions on a single page of type. It has offered vivid glimpses not only of Twain but also of the people central to his life, and it has provided a fresh index to the political and cultural nuances of the 19th century. Twain himself provided what might be the project’s motto: “Get your facts first, and then you can distort ’em as much as you please.”

To be sure, some scholars complain that Hirst and company are overdoing it. “Let Mark speak to us without a gaggle of editors commenting on his every word!” one professor grumbled. But others, like the University of Missouri’s Tom Quirk, are delighted by the painstaking effort. “It’s remarkable what good work they do,” says the author of several critical works on Twain. “Every time I’ve wanted an answer to a question, they’ve had it, and they’ve dropped all the important work they’re doing to accommodate me. And they do that for everyone, regardless of their credentials. If the Twain Project is glacial—well, we need more glaciers like that!”

The most recent example of the project’s value to scholars is the forthcoming publication of Twain’s play Is He Dead? When Shelley Fisher Fishkin, Stanford University professor and Twain scholar, told Hirst that she would like to publish the play after coming across it in the project files a year ago, he plunged into “establishing” the text for her, making sure that her edited version of the play accurately reproduced the playscript worked up by a copier in 1898 from Twain’s draft (since lost). Hirst also corrected likely errors in the copier’s version and proofread Fishkin’s introduction and postscript.

One reason for the project’s ever-lengthening timetable is that Mark Twain won’t stop writing. His known output at the time of his death at age 74 was prodigious enough: nearly 30 books, thousands of newspaper and magazine pieces, 50 personal notebooks and some 600 other literary manuscripts—fragments, chapters, drafts, sketches—that he never published.

But nearly a hundred years later, his writings continue to surface. These mostly take the form of letters, turned up by collectors, antiquarians and vintage-book sellers, and by ordinary people thumbing through boxes of dusty memorabilia stored by great-uncles and grandparents in family cellars and attics. “We now have, or know of, about 11,000 letters written by Mark Twain,” says Hirst. How many are still out there? “My conservative estimate is that he wrote 50,000 of them in his lifetime. Not all of them were long epistles. Most were business letters, replies to autograph requests—‘No, I can’t come and lecture,’ that type of thing.” Twain, of course, was capable of turning even a dashedoff line into something memorable. “I am a long time answering your letter, my dear Miss Harriet,” he confessed to an admirer whose last name does not survive, “but then you must remember that it is an equally long time since I received it—so that makes us even, & nobody to blame on either side.”

“We see them coming in at the rate of about one a week,” says Hirst. “People will walk in off the street and say, ‘Is this a Mark Twain letter?’ They even turn up on eBay.”

If 50,000 is a “conservative” estimate, what might be the high end of an informed “wild-and-crazy” sort of guess? Hirst hesitates. “My colleague, Mike Frank,” he says, “has a hunch there might be 100,000 of them in all.” since 1988, the project, through the University of California Press, has issued six volumes of Mark Twain’s letters, nearly two-thirds of them seeing print for the first time. The published volumes cover the years from 1853, when Sam Clemens was 17 and exploring New York City and Philadelphia, to 1875, by which time Mark Twain, age 40, was at work on The Adventures of Tom Sawyer and at the threshold of enduring fame. Hirst estimates that annotating Twain’s remaining 34 years’ worth of letters will take until 2021. So documenting Twain’s life will have taken 54 years, or more than two-thirds the time he took to live it.

The letters series is but one of the project’s four distinct endeavors. Another is the works of Mark Twain (scholarly editions of the writer’s published works, including his commissioned letters to various newspapers and journals). A third is the Mark Twain Library (paperback editions of the works without the scholarly notes, for classroom use and general readership). Yet a fourth, begun in 2001, is an online archive of Twain’s works and papers.

But the letters research has set the project apart. Hirst staked his career—“my life,” he says—on this vision almost as soon as he was promoted to general editor.

“When I came in, there were three volumes of letters already in proof,” Hirst recalls. “But there were only about 900 letters, total. The job had been rushed. They had done no search for new letters.”

Meanwhile, though, a colleague of Hirst’s named Tom Tenney had started to write to libraries around the country inquiring about newly found Mark Twain letters. “Well, it began to rain Xeroxes,” says Hirst. He spent two frustrating years trying to shoehorn these new discoveries into the volumes already in type. It wasn’t working. “And so I took my life in my hands and proposed to the others that we junk the proofs and start over.”

In 1983, Hirst’s proposal was implemented. It took five more years for the first revised and enlarged volume to emerge—a staggering 1,600 pages in length. The letters themselves account for less than half the total. Photographs, maps and manuscript reproductions account for several dozen more pages. But the great bulk of the volume—and of the five letters editions published since—consists of annotations.

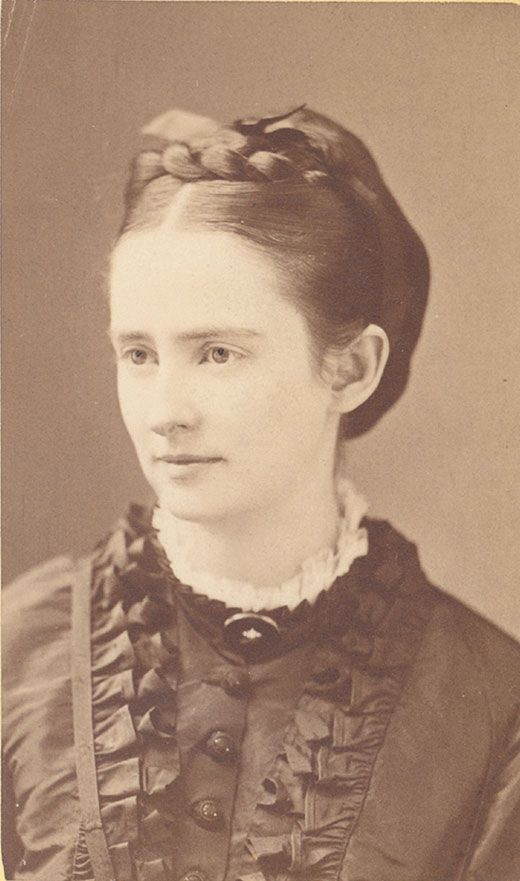

Annotations are the project’s hallmark, an ever-accumulating marvel of footnoting-as-detective-work. Most of the work is done by Hirst’s five coeditors (average length of tenure: 27 years), who hunt down virtually every reference to a person, news article, political event, or happening and explain its relevance. For example: in an 1869 letter from the lecture trail to his fiancée, Olivia (Livy) Langdon, the 33-yearold author laments affronting some young men who had shown “well-meant & whole-hearted friendliness to me a stranger within their gates.” Seizing upon the phrase “stranger within their gates,” the alert editor traced it to the Bible (Exodus 20:10)—an efficient reminder of Twain’s deep familiarity with the Scriptures, later a target of his bitter satire. The annotations enlarge the letters (as well as the published texts themselves), forming them into a kind of informational neuro-system that interconnects the private man, the public writer and the leading citizen of the 19th century.

“I’m a big believer, with Bob [Hirst], that there’s a whole world of popular culture that never makes it into the learned volumes about any given author,” says editor Lin Salamo, who arrived at the project as a 21-year-old in 1970. “Ads in newspapers of a certain period. The corner-of-your-eye stuff that may somehow work its way into a writer’s consciousness. Anyone’s life is made up of the trivial; scraps of found images and impressions. Mark Twain was a keen observer; he was a sponge for everything in his range of vision.”

Hirst doesn’t apologize for this exhaustive approach, the wails of the lean-and-meaners be damned. “Literary criticism, as I was taught it at Harvard,” he says, “emphasized the notion that you couldn’t really know an author’s intention, and so you might as well ignore it. Well, the kind of editing we do is founded on the notion that discovering the author’s intention is the first principle for anyone who is establishing a text. This kind of thinking is definitely a small and fragile backwater swamp compared to what goes on in academic literary departments.” He pauses and smiles wickedly.

“I feel enormously lucky to have found my way to this swamp.”

the “swamp” at times can seem more like an ocean, with Hirst as a kind of Ahab, pursuing the Great White Male. There is always more Twain out there, and Hirst wants all of it. Personal letters are far from the only form of Mark Twain’s writing still awaiting rediscovery. The handwritten originals of his first two major books, The Innocents Abroad and Roughing It, are still at large—if they have not been destroyed. (Finding them is not a forlorn hope: it was only 13 years ago that the long-lost first half of Adventures of Huckleberry Finn—665 pages of priceless manuscript—turned up in a Los Angeles attic, opening up a body of insights into Twain’s revision process for that seminal novel.)

Perhaps even more enticing to scholars are missing papers from the time that the adventurer Sam Clemens became the literary artist Mark Twain. These are the later dispatches that the newly pen-named Twain sent to the Virginia City (Nevada) Territorial Enterprise from the middle of 1865 through early March 1866. The Enterprise, born in the boomtown years of the Comstock silver lode, attracted a coterie of wild, gifted young bohemians to its pages, including a certain auburn-haired fugitive from Civil War duty who (luckily for American letters) proved hopeless as a prospector. Clemens wrote articles, sketches and hoaxes for the paper. Later he quit and drifted to San Francisco. There the young man hit rock bottom. Broke, unemployed, drinking, suicidally despondent, he turned again to the Enterprise, sending the paper a dispatch a day for the next several months. The work rehabilitated Clemens’ self-esteem and focused his destiny. Though several of the dispatches to the Enterprise have been preserved, most are missing.

Joe Goodman, Clemens’ editor at the paper and a lifelong acquaintance, maintained Sam never did anything better than those letters. Their loss has deprived us of a way to view Twain’s metamorphosis as a writer. Moreover, only three of his personal letters survived from all of 1865. “Anything we could recover from that period would give us an enormous advantage,” says Hirst.

A hint of the young Twain’s emerging wit during this period can be found in his send-up of a society writer’s account of a fancy dress ball: “The charming Miss M. M. B. appeared in a thrilling waterfall, whose exceeding grace and volume compelled the homage of pioneers and emigrants alike. . . . Miss C. L. B. had her fine nose elegantly enameled, and the easy grace with which she blew it from time to time, marked her as a cultivated and accomplished woman of the world. . . . ”

Hirst has worries about who—if anyone—will replace him and his staff when they retire. The editors have coalesced into a collaborative hive in which each knows the others’ areas of specialized scholarship, and can critique, reinforce or add depth to a colleague’s task of the moment.

Their discoveries often have produced new insights into Twain’s thought patterns. For example, the editors have discerned specific intentions within the 15 or so distinct ways he had of canceling out words and phrases as he wrote. “Sometimes his cancellations made the words hard to read, sometimes they made them impossible to read, sometimes he just put a big ‘X’ through a passage, and sometimes he even made a joke of his cancellations,” says Hirst, “making what I call deletions-intended-to-be-read. He did that a lot in his love letters when he was courting Livy [whom Clemens married in 1870].”

“Scold away, you darling little [rascal] sweetheart,” he wrote to her in March 1869—drawing a line through “rascal” but leaving the word legible. On another occasion, Livy wrote to ask him why he had heavily deleted a certain passage. In his reply, he made a point of refusing to answer her, and added: “You would say I was an love-sick idiot,” with the word “love-sick” obscured by looping squiggles. He then added, playfully, knowing full well that his prim and proper fiancée would not be able to resist deciphering the sentence: “I could not be so reckless as to write the above if you had any curiosity in your composition.” Apparently his deletion techniques began to preoccupy Livy: after thickly scribbling over a sentence in still another letter, he declared, “That is the way to scratch it out, my precious little Solemnity, when you find you have written what you didn’t mean to write. Don’t you see how neat it is—& how impenetrable? Kiss me, Livy—please.”

Hirst’s major innovation has been a typographic manuscript notation system that he calls “plain text.” It is a system of transcribing Twain’s manuscripts using shading, cross outs, line-through deletions and the like that allows the reader to trace the author’s stages of revision, including blank spaces he intended to fill in later, synonyms stacked above a badly chosen word or revisions scrawled in the margins—all on a single document.

For Hirst, Twain offers as much replenishment to the increasingly ineloquent contemporary world as he did to his own times. “I guess I just don’t know anyone who can move me, or make me laugh, like he can,” Hirst says, “and he can do it with things that I’ve read a dozen times before. And he can do the same thing with stuff I’ve never seen before. I don’t think I’ve ever seen anyone with as much pure verbal talent.”

As for Twain’s continuing timeliness: “I was just looking at an unpublished piece of his called ‘The Undertaker’s Tale,’ which he dashes off one summer day in his study,” Hirst says. “It’s a kind of mock Horatio Alger story, set in the family of an undertaker. Twain brings the story down to dinner and gleefully reads it to the family. Shocked silence! Livy takes him outside for a walk and talks him out of trying to publish it. But he saves it! And anybody who watches [the HBO series] “Six Feet Under” knows that in some way this is a joke that has come into modern consciousness without too much revision. He’s 130 years ahead of his time!”

with 34 years of the author’s life still to organize and annotate, the Mark Twain Project shows about as much evidence of slowing down as Ol’ Man River, though the threat of extinction due to the collapse of grant renewals has taken a growing toll on Hirst’s blood pressure, and obliged him, in recent years, to spend more time as fund-raiser than in his preferred role as a manuscript detective. Vacations, and even work-free weekends, are a rarity. He relaxes when he can with his wife of 25 years, the sculptor and painter Margaret Wade. He keeps in touch with son Tom, a sophomore at Hampshire (Massachusetts) College, steals time for daughter Emma, a high school sophomore in San Francisco across the Bay, and pursues his decades-long quest to “sivilize” (as Huck would have it) the large, sloping backyard of the family house in the Oakland hills. “There’s a stream running through it, and I’m trying to landscape it,” he says. “It’s sort of a cross between the Aswan Dam and the Atchafalaya Cutoff.”

The project got a big boost in October 2002, when the Berkeley Class of 1958 announced that in honor of its upcoming 50th reunion, it would raise funds for the project. The goal, resonating with the class’s year, is $580,000. Already, says class president Roger Samuelsen, $300,000 has been pledged. “I’ve always been a fan of Mark Twain,” says Samuelsen, a retired university director. “I go backpacking every year with my brother and friends, and we always bring along stories by Twain to read around the campfire. As for our class, we feel that this is something that goes right to the core of the university’s research and instructional values.”

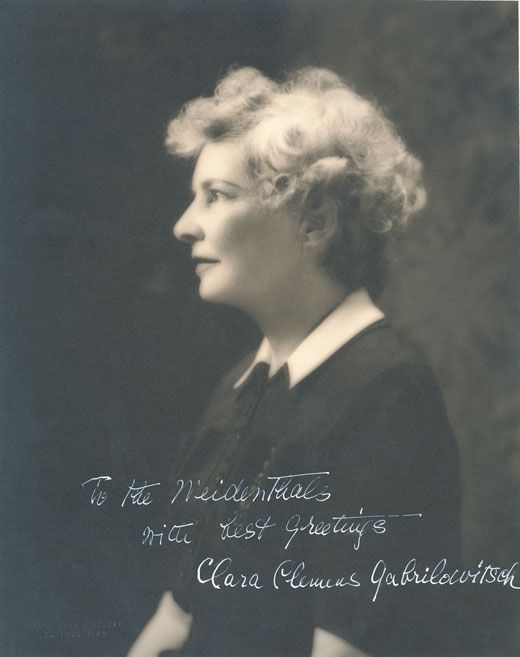

One of Hirst’s coworkers is Harriet Smith, who has spent a greater portion of her life with the author than any of her colleagues: her father, Henry Nash Smith, once oversaw the project and ranks among America’s foremost Twain scholars. “After all these years, I still keep a folder of Twain’s work that hits me,” she says. “It never ceases to amaze me—the turn of phrase, the facility for using the language that comes so naturally to him.” And, she adds, “The passion for social justice, for honesty, for exposing hypocrisy, his hatred of imperialism and war—he simply never, never goes stale.”

Her tribute would have come as no surprise to Mark Twain, who once summed up his enormous appeal with deceptive modesty. “High & fine literature is wine, & mine is only water,” he wrote to a friend. Then he added: “But everybody likes water.”