Kyrgyzstan’s Otherworldly Cities of the Dead

Photographer Margaret Morton traveled to the remote corners of the Central Asian nation to document its city-like ancestral cemeteries

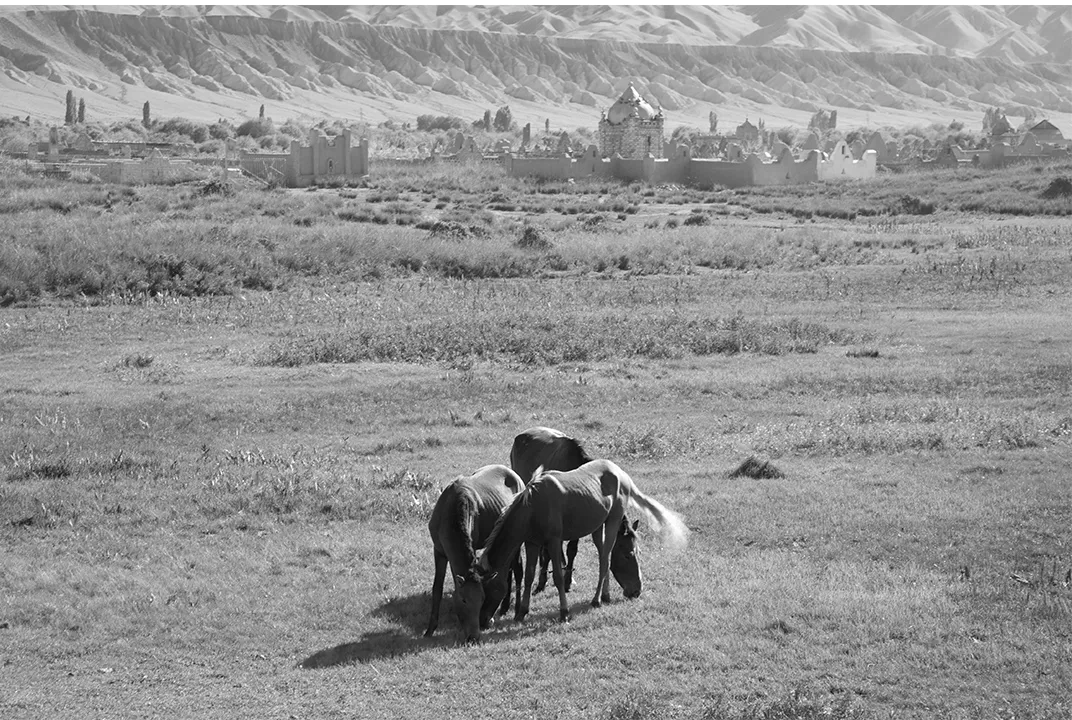

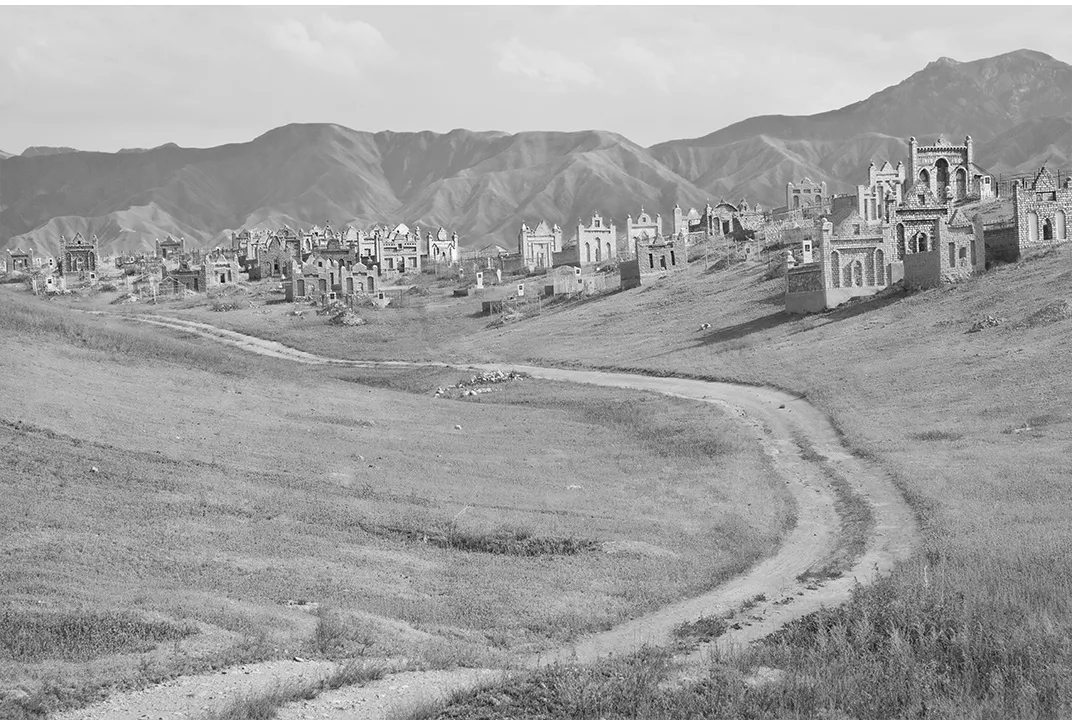

In the summer of 2006, Margaret Morton found herself in Kyrgyzstan accompanying a friend who was conducting grant research on Kyrgyz culture for a theatrical performance. One day, as they were traveling by car through lonely, mountainous terrain, she noticed what appeared to be a city in distance.

Approaching the structure, however, she realized that it was desolate and overgrown with weeds. This was not a city of the living, but a city of the dead—a Krygyz ancestral cemetery. Captivated by the site, and the others that she saw on her trip, Morton extended her stay. While her attraction was aesthetic at the start, she soon learned that the cemeteries were veritable fossils of Kyrgyzstan's multicultural past and returned for two more summers to study and document the sites. Morton’s new book Cities of the Dead: The Ancestral Cemeteries of Kyrgyzstan exhibits both the beauty and structural uniqueness of these burial grounds. I spoke with Morton, who is a professor of photography at The Cooper Union, about the project.

When you returned to Kyrgyzstan after your first trip, what were you looking to find?

I wanted to see in the different regions of Kyrgyzstan how [the cemeteries] varied, which they did dramatically.

How so?

On the Uzbekistan-Tajikistan border, they’re quite different. The images in the book with the animal horns and the yak tails—those were on the remote border regions. The one with the deer horns was actually on the north shore of Lake Issyk Kul—that area was originally settled by a tribe called the deer people.

The very grand cemeteries that I saw initially were on the south shore of Lake Issyk Kul. If they’re high up in the mountains, they’re very different. I had this theory that if the mountains are rounded and soft, the monuments have more rounded tops. I couldn’t help thinking it was just innate response. That is often the case where the people that build their own building are just responding very directly to the landscape because it’s a larger part of their lives than it is for us who live in cities.

And how did you go about finding the burial sites?

That proved more difficult that I had thought because of the roads. Kyrgyzstan is [mostly] mountains so there aren’t a lot of roads to get to places, and there aren’t a lot of paved roads—many haven’t been repaired since Soviet times—and there are a lot of mountain roads with hairpin turns, so I realized it was going to take two more summers to do what I wanted to do and to visit every region.

What elements or combination of elements in these cemeteries did you find most striking?

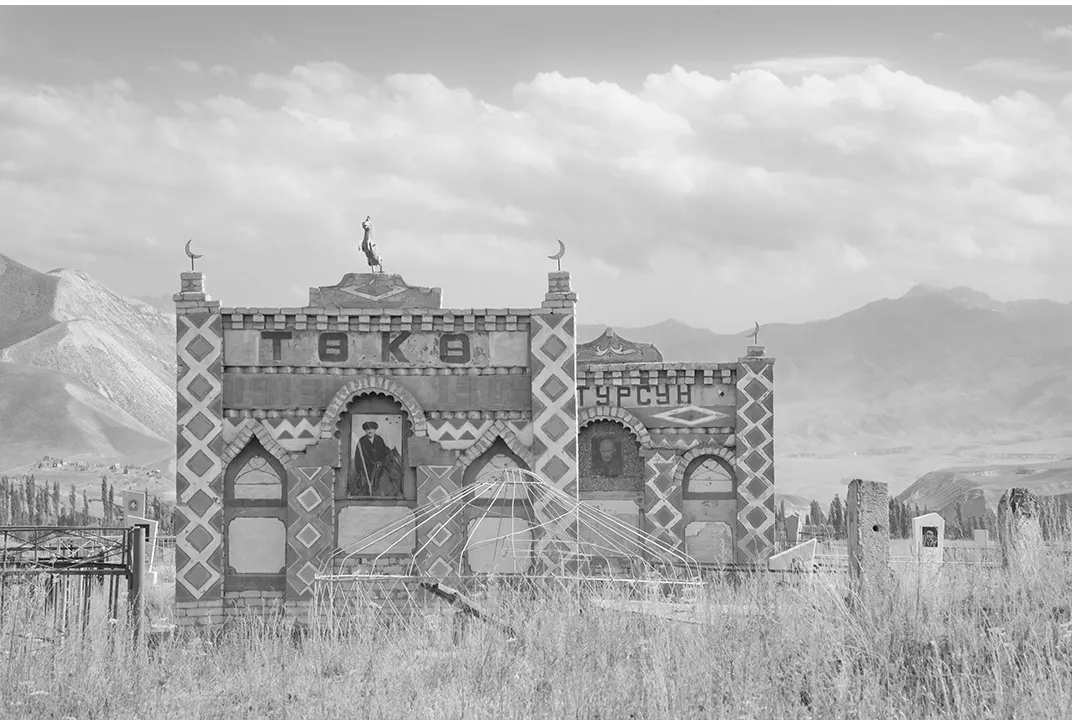

Certainly the fact that they looked like cities and that they were in this dramatic landscape. I was initially really more compelled by that response and not thinking about it as much as a burial tradition. As I learned more and more about it … the fascinating aspect was the fact that you could have nomadic references and Islamic references and Soviet references—all this could coexist in the cemetery architecture, and nobody had ever tried to change that or destroy that. That was really fascinating to me because, during the Soviet era, a lot of the important mosques were destroyed in Kyrgyzstan. But the cemeteries were never touched.

Do you think there is anything quite like this?

It seems that it’s quite unique. I did speak to artists and art historians from Kazakhstan and Tajikistan. I haven’t been to those countries, but I know a lot of people that either live there or have traveled there. They say that sometimes the cemeteries aren’t as elaborate, which is ironic because those countries do have more elaborate architecture than Kyrgyzstan. The metal structures that replicate the yurt—they said that it is unique to Kyrgyzstan. Elmira Kochumkulova, who wrote the book's introduction, had seen yak tails right on the Kyrgyz border in Tajikistan, but then she reminded me that those borders were Soviet-made borders.

Is anyone working to preserve the cemeteries?

The Kyrgz don’t preserve them. They think it’s fine that they return to the earth. A lot of [monuments] are made just from dried clay with a thin stucco, a thin clay coating over them, and you can see some of them look very soft and rounded and they wouldn’t have been when they were built, they would have had more pointed tops.

Your past four books have focused on environments of the homeless in New York. Did those projects inform this one in any way?

Absolutely. The four previous projects, even though they were centered in Manhattan and about homeless communities, were about the housing that homeless people made for themselves. [It's] this idea of people making their housing—in this case it’s housing their dead, and it’s a dramatic landscape that I was being exposed to for the first time ... what attracted me to it was the same.

Was there a reason why you chose to publish these photos in black and white?

The first summer I was photographing in black and white for my own projects. Then the second summer, I did film and then also color digital because I knew the country so much better. The color is just this pale, brown clay, usually—it’s very monochromatic. The architectural forms definitely come through better in black and white.

Do you have any projects coming up?

I’m photographing an abandoned space in Manhattan again. What will become of it I don’t know. I wanted to stay very focused on this book. I put so much energy into the project—I don’t want to let it go now that it’s finding its life in the world.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2018-08-01_at_7.20.11_PM.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2018-08-01_at_7.20.11_PM.png)