Latin America’s Wrap for All Seasons

Blanket-like “sarapes” from northern Mexico are among the world’s most intriguing textiles, as shown by a recent gallery exhibition

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20111019120006Sarapes-Maximilian-Fred-Harvey-Collection-Central-Medallion-web.jpg)

In 1978, Thomas McCormick, an art collector and gallery owner in Chicago, purchased a sarape —a wool, blanket-like textile worn by men in Latin America—from a funky, now-deceased art dealer in Los Angeles, Peggy Nusbaum. McCormick has gone on to assemble one of this nation’s most notable collections of sarapes from the Saltillo area in northern Mexico. He exhibited them in Saltillo Sarapes: A Survey, 1850-1920, at the Thomas M. McCormick Gallery. The book-sized catalogue provides, rather amazingly, the first serious scholarly attempt to describe the full development of this important art form.

As is often the case with serious scholarship, the catalogue makes clear that much of what we thought we knew isn’t true. The McCormick show attempts to set things straight.

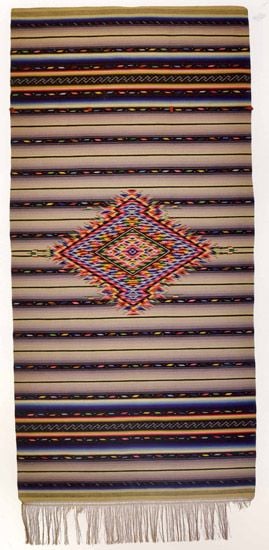

A rather simple form of attire, a sarape is curiously difficult to describe. In a way, it’s just a blanket, or a poncho with no hole in the center, although there’s generally a circular or diamond-shaped decorative motif where the head-hole would be. Its simplicity made the garment versatile. It could be worn over one’s head as a rain jacket, thrown over one’s shoulders as a cloak, draped around one’s neck as a shawl or scarf, or spread out as a blanket. When rolled behind a saddle, it provided a striking ornament. By the 1830s, as we know from costume prints by figures such as Carl Nebel, Mexican men wore sarapes in all these different ways. Women didn’t wear them. Eye-catching and decorative, sarapes let men to play the peacock.

We don’t know when sarapes first came into use. So far as the record goes, they just appear around 1835 or 1840, seemingly out of nowhere, by which time seemingly anyone who could afford a sarape was wearing one. Perhaps surprisingly, its popularity may be partly tied to tax laws: Because the sarape wasn’t traditional, it fell outside the sumptuary laws and dress codes that served as the basis for taxation.

The sarape may have evolved from the Spanish cape or capa, a large overcoat with an open front and often a hood. Alternatively, it may have evolved from the Aztec tilma, a poncho-like garment tied at the shoulder, depicted in painted codices from the 1640s. The notion of a native origin is supported by the fact that the sarape developed not in Mexico City but in outlying regions, such as Saltillo, where native traditions were more powerful. But the garment was worn by wealthy gentlemen, landowners and horsemen, most of whom belonged to an altogether different social caste and took pride in their pure Spanish descent.

Very likely it originated as a riding garment. Its use was closely associated with the huge haciendas which developed in the 18th century and were particularly powerful around Saltillo. Notably, the latifundo of the Sanchez Navarro family, with its roots in the Saltillo, was the largest estate ever owned by one family in the New World, covering some 17.1 million acres—almost 7,000 square miles. The major product of the hacienda was the wool of Marino sheep—the wool from which sarapes were woven.

Making Sense of Sarapes

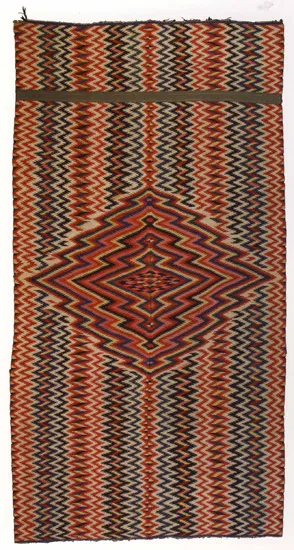

Basically, three types of sarapes can be identified. The earliest, from before about 1850, employ hand-woven wools and organic dyes—including an extremely costly red dye, cochineal, produced by pulverizing cochineal bugs, a parasite of the nopal cactus. Cochineal was a major Mexican export before the development of aniline dies. The designs of these early sarapes, generally a diamond of some sort, are linear and geometric. Many appear to have an Aztec or native quality.

The repertory of design motifs was expanded during the reign of the Emperor Maximilian, from 1864 to 1867, which ended when he was executed by the Mexican strongman Benito Juarez. Maximilian’s brief reign is associated with the introduction of design motifs from France and other European countries, and these remained popular even after he was overthrown: sarapes of this sort are known as “Maximilians.” Flowers, animals, motifs from classical architecture, portraits and other representational elements start to appear in sarapes around this period, often combined in odd ways with traditional patterns.

After about 1850, machine-woven yarn, some of it imported from Europe, began to appear in sarapes, along with synthetic, aniline dies, made from coal-tar. In transitional examples, machine-woven and hand-made yarn and natural and synthetic dies often appear in the same piece, in unusual combinations.

By the 1920s, when sarapes were produced for the delectation of American tourists, one often finds motifs that are impressively incongruous and bizarre, such as a portrait of Charles Lindbergh in a border of American red, white and blue. The fabrication of hand-woven sarapes seems to have died out in the 1930s. While sarapes are still sold in Mexico, they’re machine-made: the hand-woven sarape appears to be a thing of the past.

One of the World’s Great Textile Traditions

Sarapes are distinct from the world’s other great textile traditions. There are eye-dazzling effects, particularly in the central medallion, and some early examples vibrate like a piece of Op Art. Another recurring element is the hot reds and pinks—shrieking color that often accentuates the dazzle effects of the design motifs themselves.

The show at the McCormick Gallery has made two contributions to understanding this art form. First, it identified a small group of datable sarapes, which now can serve as touchstones for dating other examples. Second, it provided a painstakingly detailed textile analysis by Lydia Brockman, herself a weaver, which identifies the wools, the dies, and the number of threads per square inch—both warp and weft. Her analysis offers a basis for identifying related textiles or even attributing them to a maker.

It’s notable that the show took place without formal institutional support. Indeed, one of the unfortunate gaps in the catalogue is that it provides no technical analysis of some important sarapes in the Museum of International Folk Art in Santa Fe, which was reportedly not willing to unframe their pieces to be closely examined.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/henry-adams-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/henry-adams-240.jpg)