Learning to Love Sponsored Films

By any count, sponsored films are the most numerous genre of film, and they are also the ones most in danger of being lost

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20111130124020Master_Hands_thumb.jpg)

They reach back to the earliest days of the medium, yet sponsored films are a mystery to many. The genre has attracted filmmakers as varied as Buster Keaton, George Lucas and Robert Altman. In fact, it’s hard to think of a director who hasn’t made at least one: D.W. Griffith, Spike Lee, John Cleese, Spike Jonze have created sponsored films as well. Sponsored films have introduced new technologies, enlivened classrooms, won Oscars, kept studios afloat and influenced the way we watch movies and television.

By broad definition, a sponsored film is one that has been paid for by outside financing: a company or individual essentially hires or funds a crew to make a movie. In his thorough study The Field Guide to Sponsored Films, archivist Rick Prelinger cites “advertisements, public service announcements, special event productions, cartoons, newsreels and documentaries, training films, organizational profiles, corporate reports, works showcasing manufacturing processes and products, and of course, polemics made to win over audiences to the funders’ point of view.” (You can download Prelinger’s book from the National Film Preservation Foundation website.)

Estimates of the number of sponsored films reach as high as 400,000; by any count, they are the most numerous genre of film, and the films most in danger of being lost. Usually they have been made for a specific purpose: to promote a product, introduce a company, explain a situation, document a procedure. Once that purpose has been met, why keep the film?

Who would think to save Westinghouse Works, for example, a series of 1904 films extolling various Westinghouse plants and factories near Pittsburgh? Westinghouse Works was photographed by Billy Bitzer, the celebrated cinematographer who also shot D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation, and his work is always fascinating. The collection of about 20 titles, all of them single-shot films lasting at most a couple of minutes each, feature cutting-edge technology, like a camera fixed to a train circling the factory compound, and what is very probably cinema’s first crane shot, taken from over a factory floor. They were also the first films that were lit by new mercury vapor lamps, manufactured by a Westinghouse subsidiary.

As the industry matured, companies formed that specialized in sponsored films. The Worcester Film Corporation, for example, founded in Massachusetts in 1918, produced titles like Through Life’s Windows, also known as The Tale of a Ray of Light. In 1919, it made The Making of an American—a primer on how to be a good citizen—for the State of Connecticut Department of Americanization.

The Jam Handy Organization, founded by Olympic swimmer and advertising expert Henry Jamison Handy, had offices in Detroit near the General Motors headquarters. The auto giant became one of Jam Handy’s most important clients. Master Hands (1936) is a great example of how ambitious a sponsored film could be. It depicts work in a Chevrolet plant as a clanging, clashing battle to turn raw iron and steel into automobiles. Backed by a majestic score by Samuel Benavie, Gordon Avil’s cinematography borrows from the striking lighting and geometric designs of still photographers like Margaret Bourke-White. General Motors was delighted with a film that showed work so heroically, especially since the auto and steel industries were enmeshed in battles with labor unions.

Jam Handy frequently used animation in its films. Sponsors loved animation, primarily because it is usually much cheaper than filming live action. But just as important, cartoons can present messages in concrete terms that are easily understandable by a wide spectrum of filmgoers. The Fleischer brothers made sponsored films alongside their Betty Boop and Popeye cartoons. Max Fleischer directed cartoons for Jam Handy, while Dave Fleischer continued making public service announcements well into the 1950s.

Studios like Walt Disney Pictures loved sponsored films: they added certainty to budget worries, kept craftspeople employed, and offered opportunities to experiment with equipment. Cultists like to cite The Story of Menstruation for its subject matter, although it turns out to be a very straightforward lesson in biology.

Saul Bass, one of the most famous designers of the twentieth century, had a huge influence on films through his methods of “branding.” Bass helped design credits, posters, soundtrack albums and print advertising for movies like The Man with the Golden Arm (1955). He collaborated with filmmakers like Alfred Hitchcock, Stanley Kubrick and Martin Scorsese, devising remarkable credit sequences like the perpendicular lines and converge and separate in the opening of North by Northwest (1959), a hint of the criss-cross patterns that would drive the story.

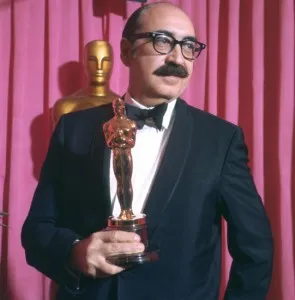

Bass also produced films for sponsors like Kodak and United Airlines. In 1968 he made Why Man Creates for Kaiser Aluminum and Chemical Corporation. Broken into eight short sections, the film used stop-motion animation, stock footage, collage and live-action scenes in what the designer called “a series of explorations, episodes & comments on creativity.” The film not only won an Oscar for Documentary—Short Subject, it had a profound impact on Terry Gilliam, who used similar techniques in his work with Monty Python. The opening credits to TV’s The Big Bang Theory also owe a debt to Why Man Creates.

One of the most purely enjoyable sponsored films came from the architectural and design team of Charles and Ray Eames. Starting in 1952 with Blacktop, they made over 125 films, smart, compact shorts that are as entertaining as they are technically advanced. They developed their own optical slide printer and animation stand, and devised one of the first computer-controlled movie cameras.

In 1977, Charles and Ray released Powers of Ten through Pyramid Films. Powers of Ten deals with scale, with how the size of an object changes relative to how and where it is viewed. It conveys an enormous amount of information with a minimum of fuss, one of the reasons why it became one of the most successful educational films of its time. One measure of its popularity is that it has been parodied more than once in the opening credits to The Simpsons.

Sponsored films continue to thrive. Chris Paine directed the powerful documentary Who Killed the Electric Car? in 2006. Five years later, General Motors helped sponsor its sequel, Revenge of the Electric Car.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/daniel-eagan-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/daniel-eagan-240.jpg)