Leonardo’s Horse?

New research may shed light on a nearly century-old theory that a sculpture thought to be ancient Greek may be da Vinci’s work

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/bronze-statuette-of-rearing-horse-631.jpg)

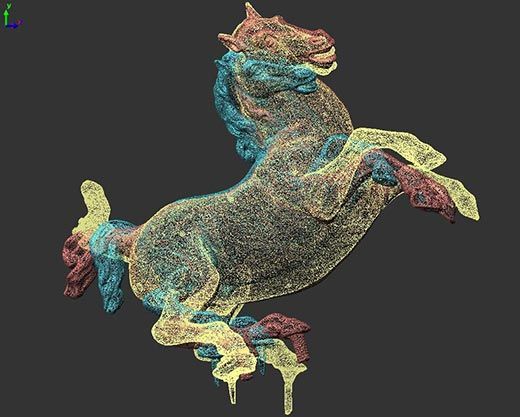

Leonardo da Vinci scholars have been puzzling over the origins of a bronze statuette of a rearing horse for nearly a century. In 1916 the similarities of the Rearing Horse and Mounted Warrior to Leonardo’s drawings led a curator at the Museum of Fine Arts in Budapest, which owns the work, to argue that the horse and rider, once thought to be an ancient Greek sculpture, was actually a Renaissance bronze, cast from a clay or wax model fashioned by the hands of the master himself. As in the case of most Leonardo claims, the attribution has never been universally accepted and study and debate are ongoing.

Recently, conservators at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. conducted extensive studies on the horse that yielded new technical evidence they say supports the possibility that it was cast from an original Leonardo model. “It doesn’t prove it was Leonardo,” said curator Alison Luchs, “but it lends weight to the idea.”

Museum conservators Shelley Sturman and Katherine May used computer models, reproductions of drawings by Leonardo, alloy analysis and x-radiographs to examine the materials and methods used to create the 10-inch-tall bronze horse. The scientific evidence suggests that the casting could have been as early as the 16th century, though perhaps after Leonardo’s death in 1519. The alloy and casting technique are characteristic of Renaissance methods, though similar methods were also used later.

Although no undisputed sculpture by Leonardo survives, historians of his time reported that he made small models as studies for his sculptures and paintings. He once scribbled a note on one of his sketches to make a small wax version of one of his drawings of a horse. He also labored for years over drawings for what was to be a 24-foot statue of a horse for Ludovico Sforza, duke of Milan. Scholars cite the artist’s sketches of rearing and twisting horses as significant evidence to support the Budapest attribution theory. The horse, which resembles the writhing stallions in Leonardo’s famous but now long-lost mural The Battle of Anghiari, squats low on its haunches in a wide stance with front legs raised, a seemingly impossible feat for a real horse. “The unnatural pose of the horse suggests someone experimenting and working out a way to do this audacious pose,” Luchs said.

The research also shows that the bronze was cast in a way that allowed preservation of the model. Of course, no one knows its whereabouts today, but the museum researchers believe “the model was not destroyed during casting, as in many cases, suggesting that it was treasured or unique,” Luchs said.

This Leonardo mystery, like others, is likely to go unsolved. “Very respected people have come to opposite conclusions,” Luchs admitted. Some say the piece lacks the signature energy of a Leonardo drawing or perhaps the model was created by someone who studied his drawings or small models. The public can explore for itself the case of the Budapest horse when it goes on view at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta as part of the Leonardo da Vinci: Hand of the Genius exhibition October 6, 2009 through February 21, 2010. Originals of Leonardo’s drawings will accompany the statue. The bronze will also be in the Leonardo da Vinci and the Art of Sculpture: Inspiration and Invention at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles, March 23 to June 20, 2010.