Letters from Vincent

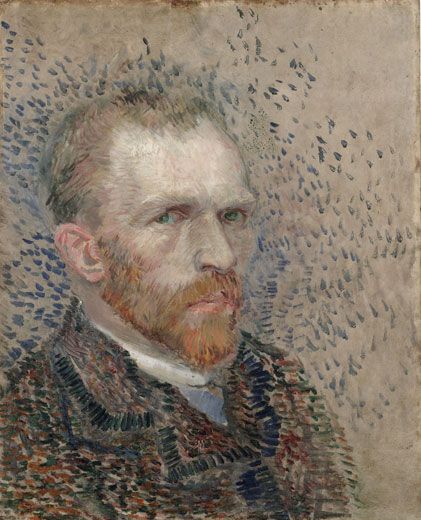

Never-before-exhibited correspondence from van Gogh to a protégé displays a thoughtful exacting side of the artist

The image of Vincent van Gogh daubing paint onto canvas to record the ecstatic visions of his untutored mind is so entrenched that perhaps no amount of contradictory evidence can dislodge it. But in an unusual exhibition at the Morgan Library & Museum in New York City (until January 6), a different van Gogh emerges—a cultivated artist who discoursed knowledgeably about the novels of Zola and Balzac, the paintings in Paris' Louvre and Amsterdam's Rijksmuseum, and the color theories of artists Eugéne Delacroix and Paul Signac. The show is organized around a small group of letters that van Gogh wrote from 1887 to 1889, toward the end of his life, during his most creative period. In the letters, he explained the thinking behind his unorthodox use of color and evoked his dream of an artistic fellowship that might inaugurate a modern Renaissance.

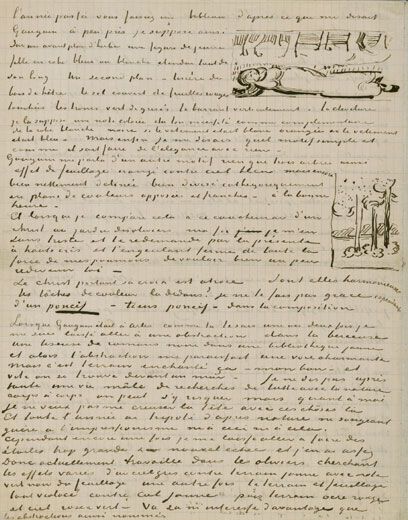

Van Gogh was writing to Émile Bernard, a painter 15 years his junior whom he had befriended in Paris a couple of years before leaving for Provence in early 1888. Of the 22 letters that he is known to have sent Bernard, all but two—one is lost, the other is held in a private collection—are on display at the Morgan, along with some of the paintings that the two artists were then producing and debating. This is the first time the letters have been exhibited. (Unfortunately, Bernard's letters in return are lost.) The bulk of van Gogh's vivid lifetime correspondence—about 800 of his letters survive—was addressed to his brother Theo, an art dealer in Paris who supported him financially and emotionally. Those letters, which constitute one of the great literary testaments in art history, are confessional and supplicatory. But in these pages to the younger man, van Gogh adopted an avuncular tone, expounding on his personal philosophy and offering advice on everything from the lessons of the old masters to relations with women: basically, stay away from them. Most important, to no one else did he so directly communicate his artistic opinions.

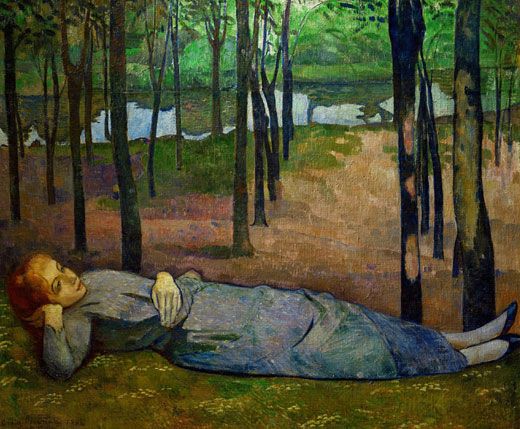

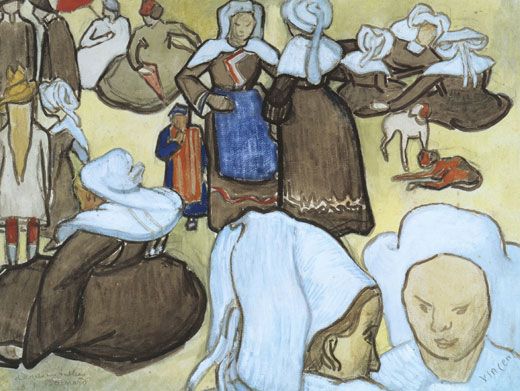

Just shy of 18 when he met van Gogh in March 1886, Bernard also impressed Paul Gauguin, whom he encountered in Brittany not long afterward. Two summers later, the ambitious Bernard would return to Brittany to paint alongside Gauguin in Pont-Aven. There, deeply influenced by Japanese prints, the two artists jointly developed an approach—using patches of flat color outlined heavily in black—that diverged from the prevailing Impressionism. Although Bernard would live to be 72, painting most of his life, these months would prove to be the high point of his artistic career. Critics today regard him as a minor figure.

In the Provençal town of Arles, where he settled in late February of 1888, van Gogh, also, was pursuing a path away from Impressionism. At first, he applauded the efforts of Bernard and Gauguin and urged them to join him in the building he would immortalize on canvas as the Yellow House. (Gauguin would come for two months later that year; Bernard would not.) There were serious differences between them, however. Exacerbated by van Gogh's emotional instability, the disagreements would later strain the friendships severely.

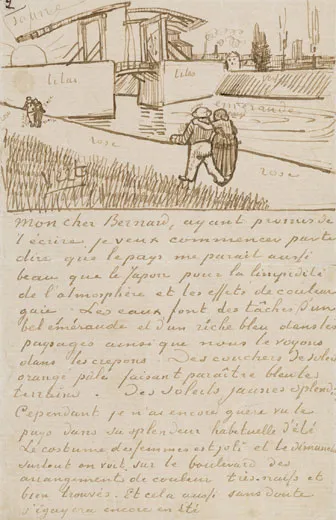

Arles, c. April 12, 1888 My dear old Bernard, ....I sometimes regret that I can't decide to work more at home and from the imagination. Certainly—imagination is a capacity that must be developed, and only that enables us to create a more exalting and consoling nature than what just a glance at reality (which we perceive changing, passing quickly like lightning) allows us to perceive.

A starry sky, for example, well—it's a thing that I should like to try to do, just as in the daytime I'll try to paint a green meadow studded with dandelions.

But how to arrive at that unless I decide to work at home and from the imagination? This, then, to criticize myself and to praise you.

At present I am busy with the fruit trees in blossom: pink peach trees, yellow-white pear trees.

I follow no system of brushwork at all, I hit the canvas with irregular strokes, which I leave as they are, impastos, uncovered spots of canvas—corners here and there left inevitably unfinished—reworkings, roughnesses....

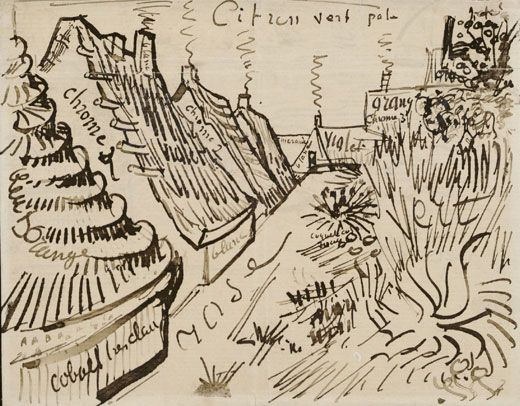

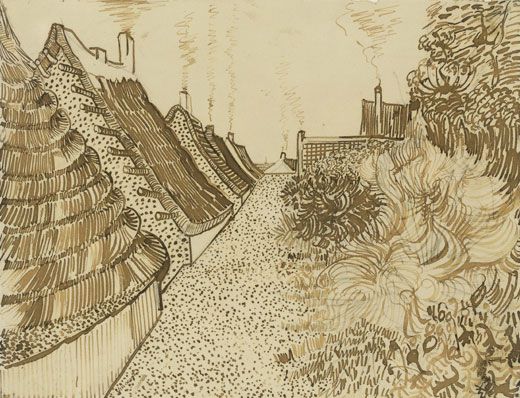

Here's a sketch, by the way, the entrance to a Provençal orchard with its yellow reed fences, with its shelter (against the mistral), black cypresses, with its typical vegetables of various greens, yellow lettuces, onions and garlic and emerald leeks.

While always working directly on the spot, I try to capture the essence in the drawing—then I fill the spaces demarcated by the outlines (expressed or not) but felt in every case, likewise with the simplified tints, in the sense that everything that will be earth will share the same purplish tint, that the whole sky will have a blue tonality, that the greenery will either be blue greens or yellow greens, deliberately exaggerating the yellow or blue values in that case. Anyway, my dear pal, no trompe l'oeil in any case....

—handshake in thought, your friend Vincent

Arles, c. June 7, 1888

More and more it seems to me that the paintings that ought to be made, the paintings that are necessary, indispensable for painting today to be fully itself and to rise to a level equivalent to the serene peaks achieved by the Greek sculptors, the German musicians, the French writers of novels, exceed the power of an isolated individual, and will therefore probably be created by groups of men combining to carry out a shared idea....

Very good reason to regret the lack of an esprit de corps among artists, who criticize each other, persecute each other, while fortunately not succeeding in canceling each other out.

You'll say that this whole argument is a banality. So be it—but the thing itself—the existence of a Renaissance—that fact is certainly not a banality.

Arles, c. June 19, 1888

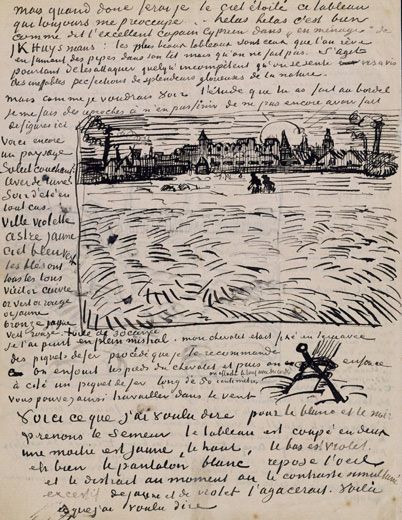

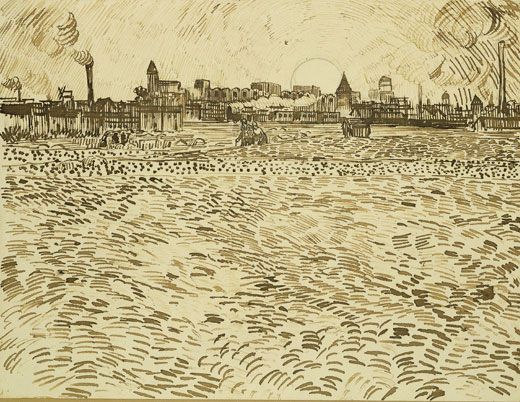

My God, if only I had known about this country at twenty-five, instead of coming here at thirty-five—In those days I was enthusiastic about gray, or rather, absence of color....Here's [a] sketch of a sower.

Large field with clods of plowed earth, mostly downright violet.

Field of ripe wheat in a yellow ocher tone with a little crimson....

There are many repetitions of yellow in the earth, neutral tones, resulting from the mixing of violet with yellow, but I could hardly give a damn about the veracity of the color....

Let's take the Sower. The painting is divided into two; one half is yellow, the top; the bottom is violet. Well, the white trousers rest the eye and distract it just when the excessive simultaneous contrast of yellow and violet would annoy it. That's what I wanted to say.

Arles, June 27, 1888

I have sometimes worked excessively fast; is that a fault? I can't help it.... Isn't it rather intensity of thought than calmness of touch that we're looking for—and in the given circumstances of impulsive work on the spot and from life, is a calm and controlled touch always possible? Well—it seems to me—no more than fencing moves during an attack.

Bernard had apparently rejected van Gogh's advice to study 17th-century Dutch masters and was instead mistakenly—in van Gogh's opinion—emulating religious paintings of such Italian and Flemish artists as Cimabue, Giotto and van Eyck. Before criticizing his junior colleague, however, van Gogh praised those of Bernard's paintings that he felt approached the standards of artists like Rembrandt, Vermeer and Hals.

Arles, c. August 5, 1888

In the first place, I must speak to you again about yourself, about two still lifes that you have done, and about the two portraits of your grandmother. Have you ever done better, have you ever been more yourself, and somebody? Not in my opinion. Profound study of the first thing to come to hand, of the first person to come along, was enough to really create something....

The trouble is, do you see, my dear old Bernard, that Giotto, Cimabue, as well as Holbein and van Eyck, lived in an obeliscal—if you'll pardon the expression—society, layered, architecturally constructed, in which each individual was a stone, all of them holding together and forming a monumental society....But you know we're in a state of total laxity and anarchy.

We, artists in love with order and symmetry, isolate ourselves and work to define one single thing....

The Dutchmen, now, we see them painting things just as they are, apparently without thought....

They make portraits, landscapes, still lifes....

If we do not know what to do, my dear old Bernard, then let's do the same as they.

Arles, c. August 21, 1888

I want to do figures, figures and more figures, it's stronger than me, this series of bipeds from the baby to Socrates and from the black-haired woman with white skin to the woman with yellow hair and a sunburnt face the color of brick.

Meanwhile, I mostly do other things....

Next, I'm attempting to do dusty thistles with a great swarm of butterflies swirling above them. Oh, the beautiful sun down here in high summer; it beats down on your head and I have no doubt at all that it drives you loony. Now being that way already, all I do is enjoy it.

I'm thinking of decorating my studio with half a dozen paintings of Sunflowers.

By now, Bernard had joined Gauguin in Pont-Aven in Britanny. As Gauguin's planned sojourn with van Gogh in Arles grew more likely, van Gogh backed away from his earlier invitations to Bernard, saying that he doubted he could accommodate more than one visitor. He also exchanged paintings with Bernard and Gauguin, expressing delight with the self-portraits they sent. But he again voiced his doubts about their practice of painting from the imagination rather than from direct observation of the real world.

Arles, c. October 5, 1888

I really urge you to study the portrait; make as many as possible and don't give up—later we'll have to attract the public through portraits—in my view that's where the future lies....

I mercilessly destroyed an important canvas—a Christ with the angel in Gethsemane—as well as another one depicting the poet with a starry sky—because the form hadn't been studied from the model beforehand, necessary in such cases—despite the fact that the color was right....

I'm not saying that I don't flatly turn my back on reality to turn a study into a painting—by arranging the color, by enlarging, by simplifying—but I have such a fear of separating myself from what's possible and what's right as far as form is concerned....

I exaggerate, I sometimes make changes to the subject, but still I don't invent the whole of the painting; on the contrary, I find it readymade—but to be untangled—in the real world.

On October 23, 1888, Gauguin moved into the Yellow House in Arles with van Gogh, while Bernard remained in Pont-Aven. Initially, the housemates got along well enough, but the relationship became increasingly turbulent. It climaxed violently on December 23, when van Gogh acted menacingly toward Gauguin, then slashed off part of his own left ear. Gauguin returned to Paris, and van Gogh recuperated in a hospital, moved back to his house and then entered an asylum in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, where he found only aloof doctors and deranged inmates for company. Although he kept in sporadic touch with Gauguin, almost a year elapsed before he would write to Bernard again.

Saint-Rémy, c. October 8, 1889

I hardly have a head for writing, but I feel a great emptiness in no longer being at all up to date with what Gauguin, you and others are doing. But I really must have patience.... Dear God, this is a pretty awful little part of the world, everything's hard to do here, to disentangle its intimate character, and so that it's not something vaguely true, but the true soil of Provence. So to achieve that, you have to toil hard. And so it naturally becomes a little abstract. Because it will be a question of giving strength and brilliance to the sun and the blue sky, and to the scorched and often so melancholy fields their delicate scent of thyme.

Bernard sent van Gogh photographs of his recent paintings, including Christ in the Garden of Olives. The older artist criticized these works severely, finding them to be inadequately imagined rather than truthfully observed.

Saint-Rémy, c. November 26, 1889

I was longing to get to know things from you like the painting of yours that Gauguin has, those Breton women walking in a meadow, the arrangement of which is so beautiful, the color so naively distinguished. Ah, you're exchanging that for something—must one say the word—something artificial—something affected....

Gauguin spoke to me of another subject, nothing but three trees, thus the effect of orange foliage against blue sky, but still really clearly delineated, well divided, categorically, into planes of contrasting and pure colors—that's the spirit! And when I compare that with that nightmare of a Christ in the Garden of Olives, well, it makes me feel sad....

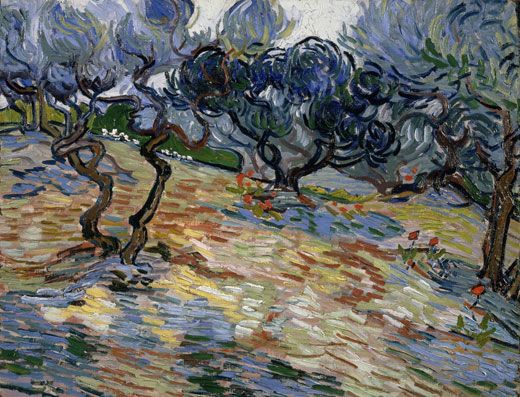

My ambition is truly limited to a few clods of earth, some sprouting wheat. An olive grove. A cypress....

Here's a description of a canvas that I have in front of me at the moment. A view of the garden of the asylum where I am....This edge of the garden is planted with large pines with red ocher trunks and branches, with green foliage saddened by a mixture of black....

A ray of sun—the last glimmer—exalts the dark ocher to orange—small dark figures prowl here and there between the trunks. You'll understand that this combination of red ocher, of green saddened with gray, of black lines that define the outlines, this gives rise a little to the feeling of anxiety from which some of my companions in misfortune often suffer....And what's more, the motif of the great tree struck by lightning, the sickly green and pink smile of the last flower of autumn, confirms this idea....that in order to give an impression of anxiety, you can try to do it without heading straight for the historical garden of Gethsemane...ah—it is—no doubt—wise, right, to be moved by the Bible, but modern reality has such a hold over us that even when trying abstractly to reconstruct ancient times in our thoughts—just at that very moment the petty events of our lives tear us away from these meditations and our own adventures throw us forcibly into personal sensations: joy, boredom, suffering, anger or smiling.

This letter ended the correspondence. Despite van Gogh's harsh words, neither man apparently viewed it as a rupture; over the next months, each inquired of the other through mutual friends. But van Gogh's "misfortune" was increasing. He moved from the Saint-Rémy asylum north to Auvers-sur-Oise to be under the care of a genial and artistically inclined physician, Paul Gachet. His psychological problems followed him, however. On July 27, 1890, following another onset of depression, he shot himself in the chest, dying two days later in his bed at the inn where he lodged. Bernard rushed to Auvers when he heard the news, arriving in time for the funeral. In the years to come, Bernard would be instrumental in expanding van Gogh's posthumous reputation, eventually publishing the letters the artist had sent to him. "There was nothing more powerful than his letters," he wrote. "After reading them, you would doubt neither his sincerity, nor his character, nor his originality; you would find everything there."

Arthur Lubow wrote about Florentine sculptor Lorenzo Ghiberti's 15th-century gilded bronze doors in the November issue.