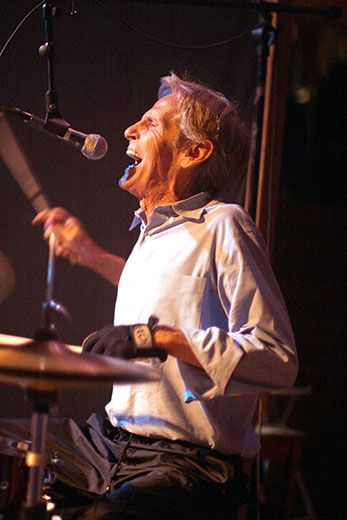

Levon Helm’s Rocking Rambles

The ‘60s rock great died today. Last July, our writer visited Helm for one of his famous Saturday night music throwdowns

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Levon-Helm-musician-631.jpg)

Editor's Note: Levon Helm died on Thursday, April 19, 2012 in New York City after losing his battle with cancer. He was 71 years old and best known as the drummer of the legendary rock group the Band. We examined Helm's extraordinary career and legacy in July 2011.

Deep in the Catskill woods the church of groove has blessed this Saturday night.

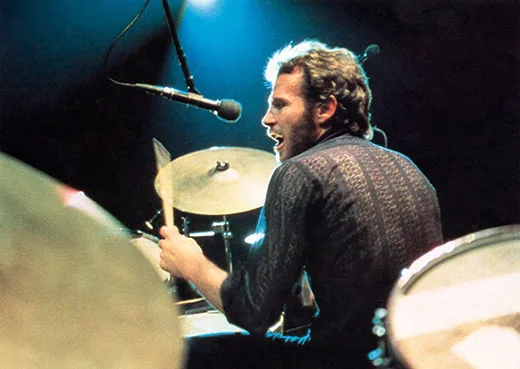

Beneath vaulted ceilings the horns blow, the women sing, the piano keys move the hammers and the drummer shakes his shoulders with the downbeat.

A guest unrecognizable in denim, bandanas and sunglasses is introduced as Conan O’Brien’s bandleader, Jimmy Vivino. He addresses the assembled crowd of 200.

“I got my musical education in this church Levon built here,” Vivino tells the crowd. “There’s something magical going on in this barn.”

With that, the Levon Helm Band kicks into the classic “Deep Ellum Blues,” about the perils of Dallas’ red-light district some 80 years ago.

The church – the barn—is the home recording studio-slash-living room of Levon Helm, an influential 1960s rock pioneer who still tours and records; his “Electric Dirt” won a 2009 Grammy. But one of his most lasting contributions to the American musical canon may just be the Saturday night musical throwdowns called the Midnight Rambles. Here in Woodstock, New York, a veteran house band welcomes neighbors, like Steely Dan’s Donald Fagen, and younger musicians, like Shawn Mullins and Steve Earle, who share Helm’s passion for song.

The sets roam over early blues, ’60s standards and recent recordings, reimagined by a 12-piece band that includes a five-man horn section, and a small music store’s worth of banjos, mandolins, a fiddle, a stand-up bass, a piano, guitars and the drums that make Helm famous.

The Rambles began in 2004 as moneymaker for Helm, who declared bankruptcy after the double blows of a house fire and cancer. The inspiration came from the traveling medicine shows of his Arkansas youth, and the musicians who played looser and talked dirtier as the night reached toward dawn.

Tickets cost $150 and go fast.

Visitors park in Helm’s yard and enter next to a garage near the barn, where tables welcome potluck dishes for ticket-holders and the volunteer staff. Inside, wooden balconies overlook the performance space, and folding chairs line the floors. A lofted back area is standing room only, so close to the band the fans could high-five the tuba player. The front row could shake the singers’ hands. Guest artists, staff and family line the wooden radiator bench – SRO folks brush by them with “excuse me” and handshakes.

There’s no monitors or video screens, no $1,000 suits or producers, no stadium echo chambers. Many audience members are musicians themselves, from former roadies to office professionals with a big bass hobby. Five-hour drives aren’t uncommon.

“If you want to know what it’s like to understand the roots and development of American music, that’s what the band was doing here in Woodstock,” says Rebecca Carrington, whose ticket was a 43rd birthday present from her husband. “This is what all the American music gets back to.”

Helm is 71. Many of his Saturday night openers are half his age.

On an icy winter Saturday night Irishman Glen Hansard dropped by. He won international fame for his movie Once. He has an Oscar and two bands – the Swell Season and the Frames – that tour the world.

The two greatest concerts he’s ever seen, he says, are Helm’s Rambles.

On that night, Hansard introduced a song inspired by Helm, so new there wasn’t a title yet. Hansard gave the band chords, rattled off a melody, asked for a riff, and they were off, Hansard nodding chord changes as he sung. Every audience member could see and hear the musician’s communication—a real-time lesson in song creation. Later, Hansard said the band members referred to chords not as letters but numbers – the 40-year-old singer called it “old school.”

Asked later if he’d try that with any other musicians, Hansard said no.

Never.

“What I feel about this band, particularly, more than any other I’ve ever seen, is that the music … is eternal,” Hansard says. “And the spirit of the music, of the right groove, is eternal. And it’s very, very rare. It nigh on doesn’t exist—people that don’t stand in the way of the music.”

“Amen,” Helm says.

“You just plug in,” Hansard says.

“Amen,” Helm says.

“And that’s what it’s all about,” Hansard says.

Gathered around Helm’s kitchen table just after midnight are Fagen, Helm’s bandleader Larry Campbell (who’s toured with Bob Dylan) and Hayes Carll, 35, an Austin-based up-and-comer whose songs appeared in the recent Gwyneth Paltrow movie, Country Strong. Chinese takeout litters the stove as Helm’s dogs wrestle over treats by the door. Hansard takes a bench.

Helm recalls one of his first musical memories. Under a segregated tent in Depression-era Arkansas, “Diamond Tooth” Mary McClain, a train-hopping circus performer with dental-work jewels, belted “Shake a Hand.”

“They’d put up a big tent and park a couple of those big tractor-trailer beds together for the stage, put a tarpaulin down, put the piano and the musicians there,” Helm says.

“Did a lot of white people go?” Fagen asks.

“Oh yeah. Down in the middle was the aisle. And the people on one side were dark to almost dark, and the people on the other side were red-haired to blond,” Helm says.

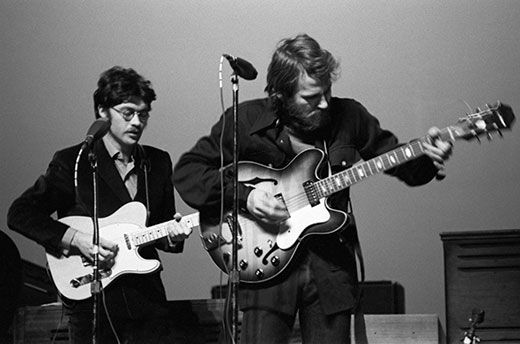

Born Mark Lavon Helm in May 1940, Helm grew up a cotton farm. Music became a way out of a hard-labor life. He showed an early gift on the drums, and as a teen toured Canada with Ronnie Hawkins and the Hawks, a precursor to the Band. Helm’s work with that ’60s roots-rock super group meshed honky-tonk, folk, blues and rock. The Band backed Bob Dylan when he went electric and appeared in The Last Waltz, the Martin Scorsese documentary that captured the group’s farewell performance. It’s considered by many to be the greatest concert film of all time.

“Good songs are good forever,” Helm says after the ramble. “They don’t get old. And a lot of the younger people they haven’t heard these good all songs, so we like to pull one or two out of the hat and pass them on.”

“We played ‘Hesitation Blues’ tonight, that was one of the good ones. ‘Bourgeoisie Blues.’ Anything that touches the musical nerve.”

Bluesman Lead Belly penned “The Bourgeoisie Blues” in 1935 in response to Washington, D.C. establishments that wouldn’t let the singer’s mixed-race group dine. Also on the set-list: the Grateful Dead’s “Shakedown Street” and slow-burning “Attics of My Life,” and Bob Dylan’s “You Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere,” written and first recorded in Woodstock with Helm’s Band bandmates (and performed in later years with Campbell backing Dylan).

No one on the road is as inviting to play with as Helm, Carll and Hansard say.

“There’s something so pure about what Levon does that makes you think it goes back ... to everything,” Carll says. “I just wanted to have my notebook out and write it all down.”