Lewis Lapham’s Antidote to the Age of BuzzFeed

With his erudite Quarterly, the legendary Harper’s editor aims for an antidote to digital-age ignorance

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Last-Renaissance-Man-Lewis-Lapham-631.jpg)

The counterrevolution has its embattled forward outpost on a genteel New York street called Irving Place, home to Lapham’s Quarterly. The street is named after Washington Irving, the 19th-century American author best known for creating the Headless Horseman in his short story “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow.” The cavalry charge that Lewis Lapham is now leading could be said to be one against headlessness—against the historically illiterate, heedless hordesmen of the digital revolution ignorant of our intellectual heritage; against the “Internet intellectuals” and hucksters of the purportedly utopian digital future who are decapitating our culture, trading in the ideas of some 3,000 years of civilization for...BuzzFeed.

Lapham, the legendary former editor of Harper’s, who, beginning in the 1970s, helped change the face of American nonfiction, has a new mission: taking on the Great Paradox of the digital age. Suddenly thanks to Google Books, JSTOR and the like, all the great thinkers of all the civilizations past and present are one or two clicks away. The great library of Alexandria, nexus of all the learning of the ancient world that burned to the ground, has risen from the ashes online. And yet—here is the paradox—the wisdom of the ages is in some ways more distant and difficult to find than ever, buried like lost treasure beneath a fathomless ocean of online ignorance and trivia that makes what is worthy and timeless more inaccessible than ever. There has been no great librarian of Alexandria, no accessible finder’s guide, until Lapham created his quarterly five years ago with the quixotic mission of serving as a highly selective search engine for the wisdom of the past.

Which is why the spartan quarters of the Quarterly remind me of the role rare and scattered monasteries of the Dark Ages played when, as the plague raged and the scarce manuscripts of classical literature were being burned, dedicated monks made it their sacred mission to preserve, copy, illuminate manuscripts that otherwise might have been lost forever.

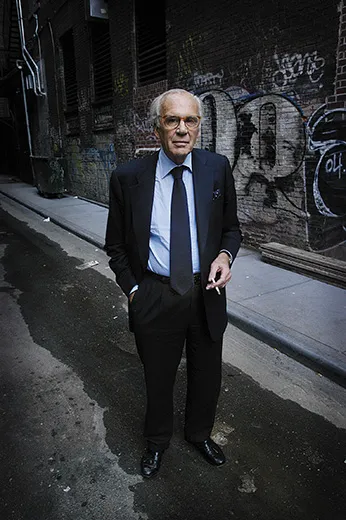

In the back room of the Quarterly, Lapham still looks like the striking patrician beau ideal, slender and silvery at 77 in his expensive-looking suit. A sleek black silk scarf gives him the look of a still-potent mafia don (Don Quixote?) whose beautiful manners belie a stiletto-like gaze at contemporary culture. One can sense, reading Lapham’s Quarterly, that its vast array of erudition is designed to be a weapon—one would like to say a weapon of mass instruction. Though its 25,000 circulation doesn’t allow that scale of metaphor yet, it still has a vibrant web presence and it has the backing of a wide range of erudite eminences.

When I asked Lapham about the intent of his project, he replied with a line from Goethe, one of the great little-read writers he seeks to reintroduce to the conversation: “Goethe said that he who cannot draw on 3,000 years [of learning] is living hand to mouth.” Lapham’s solution to this under-nourishment: Give ’em a feast.

Each issue is a feast, so well curated—around 100 excerpts and many small squibs in issues devoted to such relevant subjects as money, war, the family and the future—that reading it is like choosing among bonbons for the brain. It’s a kind of hip-hop mash-up of human wisdom. Half the fun is figuring out the rationale of the order the Laphamites have given to the excerpts, which jump back and forth between millennia and genres: From Euripides, there’s Medea’s climactic heart-rending lament for her children in the “Family” issue. Isaac Bashevis Singer on magic in ’70s New York City. Juvenal’s filthy satire on adulterers in the “Eros” issue. In the new “Politics” issue we go from Solon in ancient Athens to the heroic murdered dissident journalist Anna Politkovskaya in 21st-century Moscow. The issue on money ranges from Karl Marx back to Aristophanes, forward to Lord Byron and Vladimir Nabokov, back to Hammurabi in 1780 B.C.

Lapham’s deeper agenda is to inject the wisdom of the ages into the roiling controversies of the day through small doses that are irresistible reading. In “Politics,” for example, I found a sound bite from Persia in 522 B.C., courtesy of Herodotus, which introduced me to a fellow named Otanes who made what may be the earliest and most eloquent case for democracy against oligarchy. And Ralph Ellison on the victims of racism and oligarchy in the 1930s.

That’s really the way to read the issues of the Quarterly. Not to try reading the latest one straight through, but order a few back issues from its website, Laphamsquarterly.org, and put them on your bedside table. Each page is an illumination of the consciousness, the culture that created you, and that is waiting to recreate you.

***

And so how did it come to pass that Lewis Lapham, the standard-bearer for the new voices of American nonfiction in the late 20th century, has now become the champion for the Voices of the Dead, America’s last Renaissance Man? Playing the role T.S. Eliot, Ezra Pound and their magazine The Criterion did in the 1920s: reminding people of what was being lost and seeking some kind of restoration from the wasteland around them: “These fragments I shore against my ruin,” as Eliot wrote at the close of his most famous poem.

Lapham traces his inspiration for this venture, his sense of mission, to the spellbinding influence of one mostly forgotten soul, an intellectual historian he met at Yale named Charles Garside Jr. who dazzled him with his polymath ability. With the very idea that becoming a polymath, coming closer to knowing more about everything than anyone else, was something to strive for.

“He was an inspiring figure,” Lapham says, recalling long, late-night disquisitions in an all-night New Haven diner. “It was like I found a philosopher wandering in the academy.”

It took Lapham a while to find his way into that role himself. His great-grandfather had co-founded the oil giant Texaco and his grandfather had been mayor of San Francisco. After graduating from Yale, he got his first job as a reporter for the San Francisco Examiner, where he got a grounding in life outside books from covering the police beat, crime and punishment on the streets. He also found himself in the golden age of bohemia. “Jack Kerouac and Ken Kesey were already gone but Allen Ginsberg was still there, Kenneth Rexroth was still there and so was [beat poet icon Lawrence] Ferlinghetti.”

He left the Examiner to do a stint at the legendary New York Herald Tribune, known then as “a writer’s paper” (Tom Wolfe, Jimmy Breslin, Charles Portis, et al.). “I liked the raffishness” of that kind of newspapering, he says, but it wasn’t too long before he found himself disillusioned by the world of journalism and media.

“The election of Kennedy changed everything,” Lapham recalls. “No longer were people interested in talking about ideas—it was about access. After Kennedy’s election suddenly you had journalists wanting to be novelists and thinking that they are somehow superior to politicians. There once was [thought to be] some moral grace to being a journalist—which is of course bullshit....”

When I suggest to him that journalists had at least an edge on moral grace over, say, hedge-fund operators, he says, “Jefferson and Adams, though on opposite sides of policy, always supported the right of unhindered speech. Though they regarded journalists as vicious.”

“You believe in viciousness?”

“Yeah I do. In that it’s [journalism’s] function. But I just don’t think that’s necessarily moral grace.”

As the editor of Harper’s from 1974—with a brief interruption—to 2006, Lapham attracted a unique cast of new and celebrated writers (Tom Wolfe, Christopher Hitchens, Francine Prose and David Foster Wallace, among others) and freed them from the shackles of the third person to write in their own voice and offer readers their own truths. (It’s remarkable how many of the excerpts from the classical age in the Quarterly are in the first person. It’s ancient as well as modern.) I was fortunate to write for him, so, not being entirely objective myself, I asked New York University professor Robert S. Boynton, head of the literary reportage program there and author of The New New Journalism, to describe Lapham’s significance: “He pushed the idea that the memoir form might influence ANY piece—an essay, report, investigation—and make it more, rather than less, true. Another way to put it is that he attacked the false gods of ‘objective journalism,’ and showed how much more artful and accurate writing in the first person could be.”

Lapham left Harper’s in 2006 to found the Quarterly; he says he’d been thinking about the idea for the magazine since 1998. “I had put together a collection of texts on the end of the world for the History Book Club,” he recalls. “They wanted something at the turn of the millennium and I developed this idea by looking at the way the end of the world has ended [or been envisioned to end] many, many times and how predictions of doom have been spread across time. Whether you’re talking about the Book of Revelation or tenth-century sects. So I had this wonderful collection of texts and I thought what a great idea.

“Also it was fun,” he says.

“Here history was this vast resource; I mean truly generative. I figure that if we’re going to find our way into answers to, at least hypotheses to, the circumstances presented by the 21st century, that our best chance is to find them floating around somewhere in the historical record. I mean Lucretius, for example, writes in the first century B.C. and was rediscovered [in a monastery!] in 1417 and becomes a presence in the main work not only of Montaigne and Machiavelli but also in the mind of Diderot and Jefferson. So that history is...a natural resource as well as an applied technology.” An app!

Actually then, to call Lapham a Renaissance man is more metaphorically than chronologically accurate. He’s an Enlightenment man who embodies the spirit of the great encyclopedist Diderot, each issue of the Quarterly being a kind of idiosyncratically entertaining encyclopedia of its subject. A vast repository of clues to the mystery of human nature for the alert and erudite detective.

“In some ways you are finding a way to recreate a vision of Garside’s—your mentor at Yale....”

“Oh, I can’t do that, no I can’t,” he demurs.

“But with a staff?” In addition to 11 dedicated in-house seekers of wisdom, and an erudite board of advisers suggesting texts, he’ll recruit the occasional distinguished outside essayist.

Here’s the great Princeton scholar Anthony Grafton, for instance, taking a somewhat contrarian view (in the “Politics” issue) about the much maligned 15th-century Florentine theocrat Savonarola:

“In America now, as in Florence then, the fruit of millennial politics is a mephitic mixture of radical legislation and deliberative stalemate. Savonarola’s modern counterparts, show little of the humanity, the understanding of sin and weakness that was as characteristic of him as his desire to build a perfect city.”

Lapham speaks about his rescue mission for the sunken treasure of wisdom (not just Western—plenty of Asian, African and Latin American voices). “I can open it up to other people—again that’s my function as an editor. Somebody comes across it and reads it and thinks ‘Jesus’ and goes from a smaller excerpt in the Quarterly to the whole work by Diderot. In other words, it’s to open things up.

“We learn from each other, right? I think that the value is in the force of the imagination and the power of expression. I mean...the hope of social or political change stems from language that induces a change of heart. That’s the power of words and that’s a different power than the power of the Internet. And I’m trying to turn people on to those powers and it’s in language.”

Language as power. What a concept. “Language that induces a change of heart.”

And that, I think, is the sharp point of the Quarterly. Its very presence wounds us with our ignorance. Leaves us no excuse for not having read—or at least glimpsed—the possibilities that the history of thought offers.

But I think there’s one sentence he spoke in the beginning of his description of the Quarterly that’s important: “Also it was fun.”

***

Some are more fun than others. I must admit my favorite so far is the one on eros from Winter 2009. What a pleasure it was in the weeks after I’d left his office to read the “Eros” issue, not 224 pages straight through, but opening it at random. One found an utterly non-solemn whirligig of memorable excerpts and quotes that touched on every aspect of eros in a delightful way that left you feeling the spirit of love, longing and loss, love, physical and metaphysical, in all its manifestations, seductive and disgusted. Not a manifesto or a consideration of issues, but cumulatively an unforgettable wild ride—an idiosyncratically cohesive work of art itself, a trip! It somehow created its own genre so skillfully that one never had the sense of the dutifulness of anthology but something closer to the exhilaration of a love affair. One which was capped off by the final one-sentence quote on the final page, from Michel Foucault, of all people: “The best moment of love is when the lover leaves in the taxi.” Sigh!

***

Lapham has no love for what web culture is doing. He laments Google for inadvertent censorship in the way search engine optimization indiscriminately buries what is of value beneath millions of search results of crap. Even if that was not the purpose, it’s been the result, he avers.

“And that aspect of the Internet I think is going to get worse.”

He can sound a bit extreme when he says Facebook embodies “many of the properties of the Holy Inquisition. I mean its data-mining capacities. Or what Torquemada had in mind. I mean, the NKVD and the Gestapo were content aggregators.”

He’s nothing if not fiery. Did I hear someone say Savonarola? (Although the Florentine, who presided over “the bonfire of the vanities,” was a book-burner; Lapham is a book illuminator.)

Perhaps the best indication of his self-identification as an American revolutionary comes in his introduction to the “Politics” issue. After scornfully dismissing pay-for-play politicians of all stripes and all eras—“the making of American politics over the last 236 years can be said to consist of the attempt to ward off, or at least postpone, the feast of fools”—there is one figure he singles out for praise. One figure in American history who fearlessly told the truth, Lapham says, and paid the price for it.

He’s speaking of Thomas Paine, whose ardent 1776 pamphlet “Common Sense” sold half a million copies and, Lapham reminds us, “served as the founding document of the American Revolution.”

Nonetheless, after he was charged with seditious libel in England for challenging monarchy in “The Rights of Man,” was sentenced to death in France, and managed to offend the pious everywhere with his critique of religion, “The Age of Reason,” Paine returned home, a lonely but heroic dissident, to die in poverty, not celebrated the way the “patrician landlords”—as Lapham calls the sanctified founding fathers—are. Because, Lapham says, Paine refused to stop “sowing the bitter seeds of social change.”

Bitter to the fools at the feast at least.

The Irving Street irregulars fight on.

Ron Rosenbaum's books include, Explaining Hitler, The Shakespeare Wars, and most recently, How the End Begins: The Road to a Nuclear World War III.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/ron-rosenbaum-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/ron-rosenbaum-240.jpg)