Meet Lin-Manuel Miranda, the Genius Behind “Hamilton,” Broadway’s Newest Hit

Composer, lyricist and performer, Miranda wows audiences and upends U.S. history with his dazzlingly fresh hip-hop musical

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8e/c0/8ec08eaf-9388-4e47-9a8d-e825c9296275/dec2015_i06_historylinmanuelmiranda-web-resize-v2.jpg)

Back in June, down on Lafayette Street, Lin-Manuel Miranda stands on the lip of a stage, bent at the waist, rapping hard, spitting, sweating, pigtails flying, bouncing three rhymes in two couplets off the word “ceviche.” On a rare night out while Hamilton: An American Musical moves uptown, he’s—¿Cómo se dice?—freestyling.

Freestyle Love Supreme is the comedy/improv rap troupe he’s been part of for years. Hamilton’s George Washington, Christopher Jackson, has been too, and tonight they’re taking audience suggestions and turning them into laughs. It’s a downtown porkpie crowd heavy on the mustache wax, seersucker and loggers’ boots.

Joe’s Pub is a small cabaret across the lobby from the theater where Hamilton began. This close to Miranda, a young 35, you can watch the mind at work, hear it, feel the wheels turn, see the poet and performer up close. His gift radiates, creates a kind of heat. The quickness of his invention is remarkable, but more remarkable is the completeness of it. The sense of a finished line in the instant he’s made it. That’s the poet. The performer dares you not to love him, dares you not to be charmed, a terrible strategy for almost anyone but him. Instead he’s magnetic. In fact, his is the rarest gift of actors or singers or comics anywhere: Not only do you like him immediately, you want him to like you back. Stranger yet: He’s a better writer than he is a performer. Slender and big-eyed and tired in jeans and beautiful shoes. His energy fills the room. His T-shirt reads, “Mr. Write.” And as is often the case in Hamilton, no matter who else is center stage, he’s the one you look at.

After the show Miranda plays the room for a few minutes, shaking hands, table-hopping, cracking wise with friends. He sits with his mom and his sister as the place empties. But there’s another seating after this one, another performance he’s not part of, so they shoo him toward the door. On his way, a young man reaches out a hand. “I just wanted to thank you,” he says. That’s it. That’s all.

Miranda pauses, looks, shakes the hand. “You’re welcome,” he says like he means it and walks on.

Do I run or fire my gun?

Or let it be?

There is no beat

No melody

Burr, my first friend, my enemy,

Maybe the last face I ever see

If I throw away my shot

Is this how you’ll remember me?

What if this bullet is my legacy?

**********

The show was a hit before it ever opened.

It was the hottest ticket on Broadway before it even got to Broadway, so by the time the motorcade roared up Eighth Avenue—a block-long line of lacquer-black SUVs and limousines behind a flying wedge of motorcycle cops and siren noise—the advance ticket sales were climbing fast toward $30 million.

At the corner of 46th Street, the limousine slowed and turned and the familiar silhouette of the president of the United States leaned forward in his seat and waved to the crowds at the sidewalk barricades. In the high July heat tourists on their way to Times Square squinted and waved back and raised a small, confused cheer.

“I guess he’s here to see a show.”

“Which?”

A patrolman pointed up the block.

“Hamilton,” he said.

The limousine stopped in front of the Richard Rodgers Theatre, ringed with Secret Service agents and blastproof trucks filled with sand, and our first black president stepped inside to see our first president, black. Asked later about the show, Barack Obama said, “It is phenomenal.” It was a moment of perfect American history for those lucky enough to share it, of sharp historical clarity in our summer of Hamilton, the runaway multiracial hit.

The origin story has already hardened into legend. Lin-Manuel Miranda, precocious Tony-winning playwright and composer, lyricist and actor, takes a well-deserved vacation from his hit musical In the Heights. This is 2008. He is not yet 30 years old. Looking for a beach book, he buys Ron Chernow’s immense 2004 biography of Alexander Hamilton. In a white hammock under a blue sky beneath a hot yellow sun he reads the defining work of popular scholarship about our most mysterious founding father, and long before he’s 50 pages into it he’s wondering to himself who might have already made this extraordinary story into a play. Into a musical. He searches. Finds nothing. No one.

He takes up his keyboard and his laptop and a few months later he’s rapping what will become the show’s opening number at the White House. The YouTube video goes viral.

The next we hear of him it’s January 2015 and he’s opening a finished musical at the Public Theatre downtown with a cast as young and brash as Miranda—or Hamilton—himself.

**********

On the morning of July 11, 1804, at the foot of the bluffs in Weehawken, New Jersey, Alexander Hamilton was fatally wounded in a duel by Vice President Aaron Burr. They fought over an insult. Of the founders, Hamilton burned brightest and briefest, dead before he was 50 years old. By then he had been a war hero and aide to George Washington, authored most of the Federalist Papers and the nation’s first political sex scandal, founded the Coast Guard and the New York Post, devised and implemented a national banking system, imagined a U.S. Mint, eased America out of postwar bankruptcy and served as our first Secretary of the Treasury. He feuded with the most powerful politicians of his time, and suffers for it two centuries later. He opposed slavery. He imagined the United States as a manufacturing powerhouse and world financial leader, as a great nation of great cities with a strong, pro-business central government. Alexander Hamilton, immigrant, is the architect of the America we stand in today and the biggest star on Broadway.

You know the boilerplate biography, even if you don’t know you know it. The illegitimate son of a Scots merchant and a woman separated from her husband, Alexander Hamilton was born on the island of Nevis in the Caribbean in 1755 or 1757. His father abandoned him, his mother died, and at the age of 11 he found a job as a clerk at a trading company on St. Croix. So taken were his employers and neighbors with the boy’s intelligence and potential, they paid to send him to study in America. At 16 he enters King’s College, now Columbia, and takes up revolutionary politics. By 20 he’s a lieutenant colonel, friend to the Marquis de Lafayette, frenemy to Aaron Burr, and George Washington’s right-hand man in the fight against the British. He weds Elizabeth Schuyler, marrying into one of New York’s most distinguished families. The war won, he practices law and fights for a strong central government over the objections of men like Thomas Jefferson. To swing the debate after the Constitutional Convention in 1787, Hamilton writes at least 51 of the 85 Federalist Papers, and overwhelms the remaining naysayers and objectors with his public oratory. When Washington appoints him first Secretary of the Treasury, he is 32 years old. By his mid-30s, he is one of New York’s great men, famous everywhere in the new nation. But his limitless ambition is undone in 1797 by the lurid scandal of his affair with Maria Reynolds. Adrift in history, he loses his eldest son, Philip, to a duel in 1801. Three years later, for redress of a minor insult and under the same indifferent sky, Alexander Hamilton is mortally wounded in a duel with Aaron Burr.

Almost directly across the Hudson River from 46th Street and the Richard Rodgers Theatre are the Weehawken dueling grounds.

How does a bastard, orphan,

son of a whore

And a Scotsman, dropped in

the middle of a forgotten spot

In the Caribbean by Providence, impoverished, in squalor,

grow up to be a hero and a scholar?

**********

Long before he ever sang those words at the White House, Lin-Manuel Miranda sang them in Ron Chernow’s living room. Chernow is a Brooklyn kid who lives in Brooklyn still, but has in the meantime won the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award. He is one of America’s great biographers, in a very small class with the likes of Robert Caro and Edmund Morris and David McCullough. He is 66 years old.

His books on J. P. Morgan and John D. Rockefeller and George Washington are definitive. It took him five years to research and write his biography of Hamilton, and in doing so, Chernow rescued him from a period of recent relative obscurity and cynical misappropriation. Modern politicians find ways to blame Hamilton for the rise of Wall Street and the failure of Jefferson’s model America, a nation of picturesque villages and doughty yeoman farmers.

There’s even the question of whether or when Hamilton will come off the $10 bill. While everyone agrees it’s time for an American woman on our paper money, very few think the father of our paper money is the guy to replace. Better bloody, bloody Andrew Jackson, who killed a lot of folks—and sold many fewer tickets on Broadway.

It’s taken Miranda six years to write his own Hamilton, with Chernow checking accuracy at every draft and in every song. They’ve become close in that time, but if you want to make a person uncomfortable, ask them if someone they know is a genius.

“I’m not sure if Lin’s a genius. Hamilton was a genius,” Chernow says. “But Lin’s made a masterpiece.” (On September 28, Lin-Manuel Miranda was awarded a MacArthur Foundation “genius” grant.)

I am not throwing away my shot

I am not throwing away my shot

Hey yo, I’m just like my country

I’m young, scrappy and hungry

And I’m not throwing away my shot.

**********

And if that sounds very much like the promise of a young playwright to himself, a goad to ambition and purpose, it should. There’s as much Hamilton in Miranda as there is Miranda in Hamilton.

He’s the son of high-achieving parents from Puerto Rico, his mother a clinical psychologist and his father a political consultant. He grew up on the uppermost tip of Manhattan, near Broadway. Thirteen miles and 28 stops south on the A Train, Alexander Hamilton is buried on the same street, in the Trinity Church graveyard.

Miranda was raised in two languages and two cultures. And he grew up in a house full of music, including Broadway cast albums. So his musical influences range from Gilbert and Sullivan to Rodgers and Hammerstein, to Kander to Sondheim to Biggie and Tupac. The whole American prayer wheel from the Beach Boys to Springsteen to Willie Colón and Eddie Palmieri and Tito Puente. His influences are everything that floats through the culture. Everything. He absorbs it all—the movies, the commercials, the TV shows, the games, the books, the politics, the slang, the language, the news, the sports, the arts. And it started young.

“He was always very verbal. He read by 3, 3 1/2,” his father, Luis, will tell you. “We sent him to a local nursery school at 4 and he was the only reader, so he would read to the other kids, and the other kids would sort of be around him, because he was the one who could pick up a book. But the other thing that was always remarkable about him is that he works great as part of a team.”

Miranda and his sister, Luz Miranda-Crespo, both took piano lessons. She practiced, he didn’t. Then and now the family lived in the Inwood neighborhood, just up from Washington Heights. By the time he started commuting to Hunter College High School on 94th Street, he was writing and performing his own shows, casting, producing and directing.

He graduated and went off to Wesleyan and began writing the musical that would become In the Heights, about his familiar streets and the people he saw every day. He graduated in 2002 and kept writing. He took a job teaching English at his high school, and made ends meet by writing campaign jingles for his father’s clients.

By 2005 he and his friends, including director Thomas Kail, another Wesleyan grad, were able to mount a workshop production. In the Heights opened off-Broadway in 2007 and moved to Broadway in early 2008. It’s a salsa-inflected rap snapshot of a Dominican block in Washington Heights and the lives of its residents, the complexity of love and loss, and like Hamilton, it too is about outsider striving and ambition, about having a foot in both worlds, about being torn between home and high achievement and whatever comes next. About insecurity and purpose and achieving your own big dreams.

It won four Tony Awards and a Grammy and it launched Miranda overnight onto the short list of great American musical composers. Sondheim. Larson. Kander. Miranda. Toast of the town stuff; corner banquette at Sardi’s. Thus the New York Times “Vows” column covered his wedding in 2010. He married Vanessa Nadal, a fellow Hunter student, a graduate of MIT, a scientist and a lawyer and mother to their 1-year-old son, Sebastian.

Miranda’s a magpie, a poet and that’s as it should be, because at its best the stage musical is a mimic of its times and a synthesizing form, an amalgam of impulses and influences from every corner of the culture, and he is an industrious recorder and rewriter of those currents and moments. Like hip-hop or jazz, “the musical” as we know it is essentially American. It’s telling too that this play is at once much simpler and smarter and more complex than anything so far said or written about it by critics.

I’m ‘a get a scholarship to

King’s College

I prob’ly shouldn’t brag, but dag,

I amaze and astonish

The problem is I got a lot of

brains but no polish

I gotta holler just to be heard

And with every word, I drop knowledge!

I’m a diamond in the rough,

a shiny piece of coal

Tryin’ to reach my goal, my power

of speech unimpeachable

Only nineteen but my mind

is older

These New York City streets

get colder, I shoulder

Every burden, every disadvantage

I have learned to manage, I don’t have a gun to brandish

I walk these streets famished

The plan is to fan this spark

into a flame

But damn it’s getting dark so

let me spell out the name,

I am the —

A-L-E-X-A-N-D-E-R.

**********

His dressing room is hidden high in the rabbit warren of walk-in closets backstage. He’s in there right now, playing video games and tweeting and still—always—rewriting the season’s most successful show.

“For Hamilton what I’d do is write at the piano until I had something I liked,” Miranda recalls. “I’d make a loop of it and put it in my headphones and then walk around until I had the lyrics. That’s where the notebooks come in, sort of write what comes to me, bring it back to the piano. I kind of need to be ambulatory to write lyrics.”

He walked six years to write this show. Inwood Park. Fort Tryon Park. Central Park. Lots of shoe leather in these songs. Now he’s a new father. No wonder he’s tired.

The first act takes us from Hamilton’s beginning in the Caribbean to the end of the Revolutionary War. The second is the rap battle for the future of the Constitution and the fight for Hamilton’s marriage and reputation. And the duel.

It all moves so fast it’s hard for the audience to catch its breath. There’s a beat, a long quiet beat, at the end of the first act in which the audience gathers itself, then erupts in applause. Then they inch up the aisles to the lobby saying, “They should teach it like this in the schools.”

It’s something about the rhyme scheme of rap—or at least of the Hamilton/Miranda rap—how two propulsive couplets can wrap around into a triplet halfway into the next line and drive you forward.

“The fun for me in collaboration is, one, working with other people just makes you smarter, that’s proven,” says Miranda. “And this is not a singular art form—it’s 12 art forms smashed together. We elevate each other. And two, it’s enormously gratifying because you can build things so much bigger than yourself.”

The principal cast is so good you wonder how everyone seems so right for the part. “Because we spend more time casting than anyone else,” says director Thomas Kail. Everyone will come out of this show a star. Or a bigger star. “I spend time picturing them in movies and TV after this,” Miranda says. “On Law & Order, like the cast of Rent.”

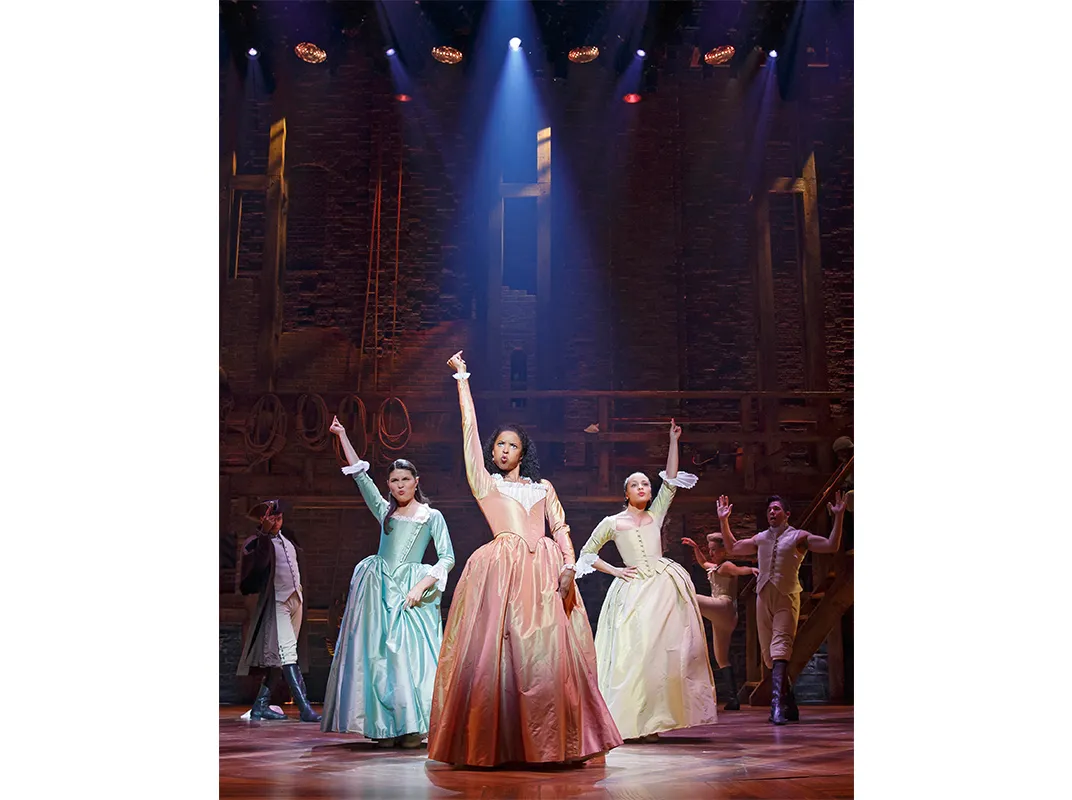

It’s hard to gauge who’ll break biggest, but watching Leslie Odom Jr. as Burr in “The Room Where It Happens” is a lot like seeing Ben Vereen take the stage for the first time in Jesus Christ Superstar, a watershed for performer and audience. It’s his show in many ways. Daveed Diggs as a louche Thomas Jefferson channeling Cab Calloway and the Looney Tunes wolf. Jonathan Groff as King George with the show’s peak comic moment, an imperial homage to Britpop teen heartbreak and the early Beatles. Every Schuyler sister: Renée Elise Goldsberry, Phillipa Soo, Jasmine Cephas Jones.

This may be the most collaborative business there is, so credit goes in equal measure to every part of the creative team, even if the profiles take the “solitary genius” approach. Kail; Alex Lacamoire, music director; Andy Blankenbuehler, choreographer—Miranda calls it “The Cabinet.” It’s all one thing. One brain. They all worked together on In The Heights. You see them at rehearsal, in the calm eye of the Broadway hurricane, working and working and reworking what already works. They gesture with their coffee cups to the lights, the wings, the turntable. Maybe try this, maybe trim that. Maybe coffee is the real genius.

“It’s about making the best possible thing,” Miranda says.

The show is somehow overtly political without seeming so, as is the timing of its arrival. Oskar Eustis, the artistic director of the Public Theater, told the Los Angeles Times as much in June. “My wise friend Tony Kushner,” said Eustis, “pointed out to me that the success of Hamilton is precisely embodied in the fact that it is convincing everybody of the need to see this nation as a nation of immigrants—the need to see people of color as central to owning the nation. I think the show is actually going to move the needle on how we think about immigration precisely because it’s reaching people.”

We’re all here from somewhere else. America, Mother of Exiles.

There’s a lottery for $10 front-row seats before every show. A nice touch of egalitarianism in the face of Broadway prices, with a little P.T. Barnum thrown in. Crowds of 600 or 700 people gather and cross their fingers.

Somehow, in less than a year, Hamilton has become emblematic of something much bigger than itself. There’s a lesson here for everyone, American or not. “The U.N. Security Council came to see the show at the Public,” Miranda remembers one afternoon, “and our U.S. ambassador said, ‘There are so many world leaders I would love to bring to the show just to show them George Washington stepping down—because the story of history is leaders leading on populism, then not leaving.’’’

**********

The night of that presidential matinee there’s a party for the cast of Hamilton. Down the street and around the corner from the theater, it’s upstairs at a club on Times Square. Here, inside, flattered by candlelight, everyone is beautiful, the music falls from the rafters and there’s never a line at the bar. There’s even a red carpet for photo ops. This is what success looks like, what you pretend for yourself as a kid hamming it up in the mirror at home in Kenosha or Youngstown or Washington Heights. Parties like this are part of the dream.

The place smells like money and the waiters glide by in silence with free drinks and tiny food. The cast arrives and the cameras strobe and the dancers dance as soon as they walk in the door. Miranda moves from group to group distributing hugs and wisecracks to cast members, their wives, their boyfriends, their husbands. Every conversation is a variation on the theme of “What a day. The president.” The dance floor fills. After an hour, Miranda wanders away from the noise and the crowd and tucks himself into a corner, half hidden by a column and a cocktail table. He sits on the windowsill and takes out his phone.

He sits alone for what seems a long time. Immersed. Maybe he’s texting goodnight to his wife and son. But he could easily be writing notes for revisions to the show.

If it’s good, why try to make it great?

“Because those are the shows we love. We love Fiddler. We love West Side Story. I want to be in that club. I want to be in the club that writes the musical that every high school does. We’re this close.”

Or maybe he’s starting on the next one. Chernow hopes he has eight or ten more of these in him. Rapt, his tired face washed smartphone blue, behind him the sidewalks teem and the Times Square light show explodes. Eventually a couple of people find him. One yells over the music, “We just wanted to thank you.” He smiles and rises to meet them.

The show is successful because the show is so good, and the show is so good largely because of Lin-Manuel Miranda. His secret is that he writes in service of character, to advance story. He doesn’t write merely to be clever, to show off. Without having to contrive event or fabricate plot he breathes life into history and Alexander Hamilton, animates him, stands him up and makes him sing, makes him human for a couple of hours.

“A genius? I’m not sure what that word means,” his father said one morning. “What I admire most about him is his humility.”

So maybe Miranda’s genius lies in his willingness not to behave like a genius—an outlier, a singularity—but rather to dissolve himself into the group, the collective in which ideas and improvements are argued on their merits.

A democracy in which the best idea wins.

Or maybe he’s not a genius at all, just a hard-working young playwright with a great ear and a good heart who loves words and people—so people and words love him back. All those things. None of those things. Does it matter? He helped make a masterpiece.

And when my time is up?

Have I done enough?

Will they tell my story?

**********

Three weeks later, it’s opening night. A few hours before the six o’clock drawing for those $10 tickets, Lin-Manuel Miranda reads aloud into the August heat the first five paragraphs of Ron Chernow’s biography of Alexander Hamilton. He chokes up, as do many of the 600 people listening to him.

“Yes,” reads the overnight review in the New York Times, “it really is that good.” The show is a hit. Already. Still. At midnight there’s another cast party. Fireworks on the Hudson. Everyone is there and everyone is happy and with every shot the big river brightens and burns all the way to Weehawken. The rest is history.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jeff_MacGregor2_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jeff_MacGregor2_thumbnail.png)