LISTEN NOW: Wu Man Brings East and West Together in New Album

In Borderlands, the Chinese musician highlights the culture of the Uyghur people

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Playlist-Wu-Man-631.jpg)

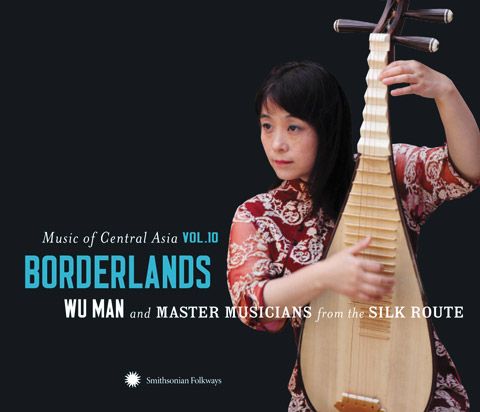

Wu Man’s innovative arrangements combining musical traditions of the East and West have made her one of the world’s most important musical ambassadors. Classically trained in the Pudong School, Wu’s unmatched skill on the pipa, an ancient Asian lute, has led to partnerships with Yo-Yo Ma and the Kronos Quartet, among others. In Borderlands, out on May 29 from Smithsonian Folkways Recordings, Wu turns her attention to the marginalized Uyghur people in the outer reaches of her homeland. In an interview with the magazine’s Aviva Shen, Wu reflects on their common roots and the differences in musical tradition.

What inspired you to make this album?

I have been really interested in the west part of China for many, many years. I grew up familiar with the Uyghur music, listening to a lot of folk songs. But it was very much reconstructed by Chinese, not Uyghur. So I’m really interested in what’s the original style of Uyghur music. This project was a dream come true.

How did you find the Uyghur musicians?

It was actually a long process. I worked with Ted Levin, an expert on central Asian music from the Aga Khan Foundation. And we worked together with Rachel Harris, a professor at the University of London, whose specialty is Uyghur music. We wanted to have something really authentic, because there are a lot of music groups in Beijing and Shanghai that call themselves Uyghur. But we wanted to go to the village to find what was there. Rachel sent me a lot of different CDs and recommended different artists or masters, and I decided which ones I wanted to work with. It took a year and a half or two years, the whole process. I didn’t get a chance to go to those villages. That time was very sensitive [In July 2009, riots in the Uyghur city of Xinjiang destabilized Uyghur-Chinese relations]. But I got their phone numbers and just called them. I talked about the idea and why I wanted to work with them. Then we all gathered in Beijing. At first we just rehearsed and tried out things. The second time we met, we had a much clearer idea of what we wanted to do. We spent three days in studio in Beijing. It was very enjoyable.

What was it that so fascinated you about this region?

The West part of China was to me always kind of mysterious. We have this song about the area; how beautiful the mountains are, how blue the sky is. I grew up with this idea that that was the dream place I wanted to go to. And the Uyghur people are very good at dance. In the big city, we still see them on TV dancing and singing. Their songs are very different from my tradition of Chinese music. My tradition is more of a scholarly type of music: serious and meditative. And Uyghur music is totally the opposite. They’re very warm and impassioned. That kind of style really attracted me.

Are most Chinese not very familiar with Uyghur music and culture?

On the surface we know they have beautiful dance and singing, but that’s all we know. We don’t understand the tradition—what is muqam [the melody type], what are they singing about. As a musician I wanted to know the structure of the piece, how developed it was. My instrument, pipa, actually came from Central Asia. It’s not invented by the Chinese. Two thousand years ago it came from a Persian. Abdullah [a Uyghur musician who collaborated on the album] said, “A thousand years ago we were from the same family. We parted maybe 800 years ago, and now we’ve found each other back together.” It was very touching.

You’ve focused in the past on the combination of Eastern and Western traditions. How is this project different from other things that you’ve done?

I came to the United States in 1990 and I spent a lot of time doing the East and West. I grew up in China and I wanted to know the history behind Western music, the similarities with Chinese music. But this project is East meets East. Although it’s the west of China, it’s the same tradition. It’s a rediscovery of my musical roots.

What do you hope people take away from this album?

First of all, I hope people will open their minds and accept this kind of combination. I want them to enjoy the music. It reminds me of a concert I just had in Taipei, where I worked with Taiwanese aboriginal singers. Before that concert, everyone in the music circle and general audience was very curious about how the Chinese pipa could work with aboriginal musicians. But after the concert, we got a standing ovation. That is very weird, that a Chinese audience would be so enthusiastic. Lots of people came up to me and said the concert really changed their mind about Taiwanese music. They never thought those different cultures could combine and become something else. This is the same idea. First, it’s rediscovering my instrument’s roots, but also I want the audience to enjoy and open their minds. I’m not a political person, but I do feel that it’s important to know each other and understand other cultures that are right next to you.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/ATM-aviva-shen-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/ATM-aviva-shen-240.jpg)