Living With Geese

Novelist and gozzard Paul Theroux ruminates about avian misconceptions, anthropomorphism and March of the Penguins as “a travesty of science”

When I first began to raise geese, in Hawaii, my more literate friends asked me, "Have you read the E. B. White piece?" This apparently persuasive essay was all that they knew about geese other than the cliché, often repeated to me, "Geese are really aggressive! Worse than dogs!" or "They're everywhere!"—regarding them as an invasive species, spoiling golf courses. Received wisdom is not just unwise, it is usually wrong. But I was well disposed toward E. B. White. In his writing he is the kindest and most rational observer of the world. And a man who can write the line "Why is it...that an Englishman is unhappy until he has explained America?" is someone to cherish.

Though I had read much of White's work, I had not read his essay "The Geese." I avoided it for several reasons. The first was that I wanted to discover the behavior of these birds, their traits and inclinations, on my own, at least in the beginning. I loved the size of geese, their plumpness, their softness, the thick down, the big feet of fluffy just-born goslings, the alertness of geese—sounding an alarm as soon as the front gate opened; their appetites, their yawning, the social behavior in their flocking, their homing instinct, the warmth of their bodies, their physical strength, their big blue unblinking eyes. I marveled at their varieties of biting and pecking, the way out of sheer impatience a goose wishing to be fed quickly would peck at my toes, just a reminder to hurry up; the affectionate and harmless gesture of pecking if I got too close; the gander's hard nip on the legs, the wicked bite on my thigh, which left a bruise. I also marveled at their memory, their ingeniousness in finding the safest places to nest; their meddling curiosity, always sampling the greenery, discovering that orchid leaves are tasty and that the spiky stalks of pineapple plants are chewable and sweet.

But it was the second and more important reason that kept my hand from leaping to the shelf and plucking at the Essays of E. B. White. It was White's conceits, his irrepressible anthropomorphism, his naming of farm animals, making them domestic pets, dressing them in human clothes and giving them lovable identities, his regarding them as partners (and sometime personal antagonists). Talking spiders, rats, mice, lambs, sheep and pigs are all extensions of White's human world—more than that, they are in many cases more sensitive, more receptive, truer chums than many of White's human friends.

But here's the problem. White's is not just a grumpy partiality toward animals; rather, his frequent lapses into anthropomorphism produce a deficiency of observation. And this sets my teeth on edge, not for merely being cute in the tradition of children's books, but (also in the tradition of children's books) for being against nature.

Animal lovers often tend to be misanthropes or loners, and so they transfer their affection to the creature in their control. The classics of this type are single species obsessives, like Joy Adamson, the Born Free woman who raised Elsa the lioness and was celebrated in East Africa as a notorious scold; or Dian Fossey, the gorilla woman, who was a drinker and a recluse. "Grizzly man" Tim Treadwell was regarded, in some circles, as an authority on grizzlies, but Werner Herzog's documentary shows him to have been deeply disturbed, perhaps psychopathic and violent.

Assigning human personalities to animals is the chief trait of the pet owner—the doting dog-lover with his baby talk, the smug stay-at-home with a fat lump of fur on her lap who says, "Me, I'm a cat person," and the granny who puts her nose against the tin cage and makes kissing noises at her parakeet. Their affection is often tinged with a sense of superiority. Deer and duck hunters never talk this way about their prey, though big game hunters—Hemingway is the classic example—often sentimentalize the creatures they blow to bits and then lovingly stuff to hang on the wall. The lion in Hemingway's story "The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber" is sketched as one of the characters, but that is perhaps predictable given Hemingway's tendency to romanticize what have come to be called charismatic megafauna. Moby-Dick is wicked and vengeful, and Jaws was not a hungry shark but a villain, its big teeth the very symbol of its evil. And goodness is embodied in the soulful eyes of a seal pup, so like a 6-year-old that at seal culling season you find celebrities crawling across ice floes to cuddle them.

The literature of pets, or beloved animals, from My Dog Tulip to Tarka the Otter, is full of gushing anthropomorphists. The writers of nature films and wildlife documentaries are so seriously afflicted in this way they distort science. How many ant colonies have you seen on a TV screen while hearing, "Just putting that thing on his back and toiling with his little twig and thinking, I've just got to hang on a little while longer," speaking of the ant as though it's a Nepalese Sherpa.

Possibly the creepiest animals-presented-as-humans film was March of the Penguins, a hit movie for obviously the very reason that it presented these birds as tubby Christians marooned on a barren snowfield, examples to be emulated for their family values. When a bird of prey, unidentified but probably a giant petrel, appears in the film and dives to kill a chick, the carnage is not shown nor is the bird identified. The bird is not another creature struggling to exist in a snowfield but an opportunistic mugger from the polar wastes. We are enjoined to see the penguins as good and the giant petrel as wicked. With this travesty of science people try to put a human face on the animal world.

This is perhaps understandable. I've named most of my geese, if only to make sense of which one is which, and they grow into the name. I talk to them. They talk back to me. I have genuine affection for them. They make me laugh in their wrongheadedness as well as in the ironies of their often-unerring instincts. I also feel for them, and I understand their mortality in ways they cannot. But even in the pathos, which is part of pet owning, I try to avoid anthropomorphizing them, which is the greatest barrier to understanding their world.

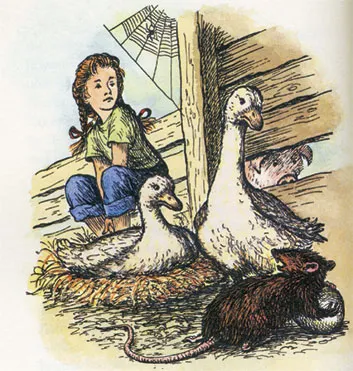

But E. B. White patronizes his geese and invents feelings for them and obfuscates things. After years of goose rearing, I finally read his essays and, as I feared, was in the company of a fanciful author, not an observant gozzard, or goose rearer. Here was "a gander who was full of sorrows and suspicions." A few sentences later the gander was referred to as "a grief-crazed old fool." These are the sentimentalities you find in children's books. A goose in White's "classic" story about a spider, Charlotte's Web, says to Wilbur the pig, "I'm sitting-sitting on my eggs. Eight of them. Got to keep them toasty-oasty-oasty warm."

Edward Lear was also capable of writing in this whimsical vein, yet his paintings of birds rival Audubon's in dramatic accuracy. Lear could be soppy about his cat, but he was clearsighted the rest of the time. E. B. White is never happier than when he is able to depict an animal by humanizing it as a friend. Yet what lies behind the animal's expression of friendship? It is an eagerness for easy food. Feed birds and they show up. Leave the lids off garbage cans in Maine and you've got bears—"beggar bears" as they're known. Deer love the suburbs—that's where the easiest meals are. Woodchucks prefer dahlias to dandelions. The daily imperative of most animals, wild and tame, is the quest for food, which is why, with some in your hand, you seem to have a pet, if not a grateful pal.

White's geese are not just contented but cheerful. They are also sorrowful. They are malicious, friendly, broken-spirited. They mourn. They are at times "grief-stricken." White is idiosyncratic in distinguishing male from female. He misunderstands the cumulative battles that result in a dominant gander—and this conflict is at the heart of his essay. He seems not to notice how at the margins of a flock they bond with each other—two old ganders, for example, keeping each other company. It seems to White that geese assume such unusual positions for sex that they've consulted "one of the modern sex manuals." Goslings are "innocent" and helpless. When I came across the gander White singled out as "a real dandy, full of pompous thoughts and surly gestures," I scribbled in the margin, "oh, boy."

During ten years of living among geese and observing them closely, I have come to the obvious conclusion that they live in a goose-centric world, with goose rules and goose urgencies. More so than ducks, which I find passive and unsociable, geese have a well-known flocking instinct, a tendency to the gaggle. This is enjoyable to watch until you realize that if there is more than one gander in the flock, they will fight for dominance, often quite vocally.

Their sounds vary in pitch and urgency, according to the occasion, from wheedling murmurs of reedy ingratiation, along with the silent scissoring of the beak, as they step near knowing you might have food, to the triumphant squawk and wing-flapping of the gander after he has successfully put to flight one of his rivals. In between are the ark-ark-ark of recognition and alarm when the geese see or hear a stranger approach. Geese have remarkable powers of perception (famously, geese warned the Romans of the Gallic invasion in 390 b.c.); the hiss of warning, almost snake-like, the beak wide open, the agitated honk with an outstretched neck, and—among many other goose noises—the great joyous cry of the guarding gander after his mate has laid an egg and gotten off her nest. Ducks quack, loudly or softly, but geese are large eloquent vocalizers, and each distinct breed has its own repertoire of phrases.

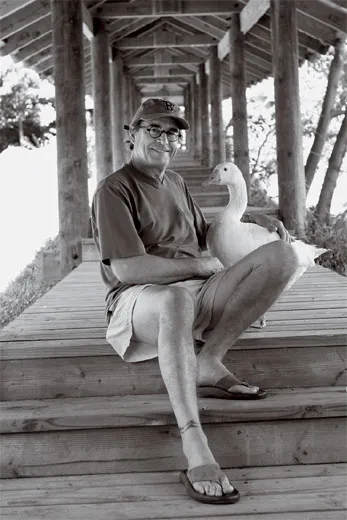

My first geese began as three wobbly goslings, scarcely a day old, two ganders and a goose. The goose became attached to one of the ganders—or perhaps the other way round; the superfluous gander became attached to me—indeed "imprinted" on me so deeply that even years later he will come when called, let his feathers be groomed, scratched and smoothed, and will sit on my lap without stirring, in an astonishing show of security and affection. Konrad Lorenz describes this behavior as resulting from a gosling's first contact. Affection is of course the wrong word—mateship is more exact; my gander had found a partner in me because his mother was elsewhere and no other goose was available.

Every day of the year my geese range over six sunny Hawaiian acres. Penning or staking them, as some gozzards do in northern latitudes, is unthinkable. White mentions such captivity in his essay but makes no judgment: it is of course cruel confinement, maddening big birds, which need lots of space for browsing, rummaging and often flying low. When it comes time to sex young geese, the process is quite simple: you tip the birds upside down and look at the vent in their nether parts—a gander has a penis, a goose doesn't. A little later—weeks rather than months—size and shape are the indicators; the gander is up to a third bigger than the goose.

White never mentions the breed of his geese, another unhelpful aspect of his essay, but if they were Embdens, the gander would be 30 pounds at maturity and the goose five to ten pounds lighter; English gray geese are bigger, China geese a bit smaller, and so forth, but always the gander heavier than his mate. I have raised Toulouse geese, China geese, Embdens and English grays. Toulouse are usually overwhelmed by the Embdens, which seem to me to have the best memories and the largest range of sounds. Embdens are also the most teachable, the most patient. China geese are tenacious in battle, with a powerful beak, though a full-grown English gray gander can hold its ground and often overcome that tenacity.

Spring is egg-laying time. When there is a clutch of ten or a dozen eggs, the goose sits on them and stays there in a nest made of twigs and her own fluffy breast feathers. The goose must turn her eggs several times a day, to spread the heat evenly. Performing this operation hardly means withdrawing from the world, as White suggests. Though a sitting goose has a greatly reduced appetite, even the broodiest goose gets up from her nest now and then, covers her warm eggs with feathers and straw and goes for a meal and a drink. The gander stands vigil and, unusually possessive in his parental phase, fights off any other lurking ganders. When the goslings finally appear, they strike me as amazingly precocious—indeed the scientific word for their condition is precocial, which means they are covered with soft feathers and capable of independent activity almost from the moment of hatching. After a few days they show all the traits of adult behavior, adopting threat postures and hissing when they are fearful.

An established gander will carefully scrutinize new goslings introduced into his flock. It is simply a bewildered gander being a gander, acting out a protective, perhaps paternal possessive response. It is acting on instinct, gauging where the goslings fit in to his society. Their survival depends on it.

Geese develop little routines, favorite places to forage, though they range widely and nibble everything; they get to like certain shady spots, and through tactical fighting, using opportunities, they establish leadership; they stay together, they roam, and even the losers in the leadership battles remain as part of the flock. White's geese, which had to endure the hard Maine winters, were often confined to a barn or a pen, which are prisons producing perverse over-reactive, defensive, aggressive behavior, as all prisons do.

The gander takes charge in normal surroundings: it is part of his dominance—keeping other ganders away. He rules by intimidation. He is protective, attentive and aggressive in maintaining his superior position among all the other birds, and will attack any creature in sight, and that includes the FedEx deliveryman way up at the front gate. When young ganders grow up, they frequently challenge the older one. The victor dominates the flock, and the goslings have a new protector. The old gander has merely lost that skirmish and has withdrawn, because he is winded and tired and possibly injured. But win or lose they remain with the flock. Defeated ganders go off for a spell to nurse their wounds, but they always return. One of the most interesting aspects of a flock is the way it accommodates so many different geese—breeds, sexes, ages, sizes. Ganders go on contending, and often an old gander will triumph over the seemingly stronger young one. Only after numerous losing battles do they cease to compete, and then a nice thing happens: the older ganders pair up and ramble around together at the back of the flock, usually one protecting the other.

There is a clue to White's self-deception in this part of the essay: "I felt very deeply his sorrow and his defeat." White projects his own age and insecurity onto the gander. "As things go in the animal kingdom, he is about my age, and when he lowered himself to creep under the bar, I could feel in my own bones his pain at bending down so far." This essay was written in 1971, when White was a mere 72, yet this is the key to the consistent anthropomorphism, his seeing the old gander as an extension of himself—a metonymical human, to use French anthropologist Claude Levi-Strauss' definition of such a pet. The essay is not strictly about geese: it is about E. B. White. He compares the defeated gander to "spent old males, motionless in the glare of the day" on a park bench in Florida. He had shuttled back and forth from Maine to Florida; his anxiety is real. He mentions summer sadness twice in his essay, a melancholy that may sadden a person precisely because the day is sunny.

What saddens me about this confident essay is that White misses so much. Because he locks up his geese at night, he never sees the weird sleeping patterns of geese. They hardly seem to sleep at all. They might crouch and curl their necks and tuck their beaks into their wings, but it is a nap that lasts only minutes. Do geese sleep? is a question that many people have attempted to answer, but always unsatisfactorily. If they are free to ramble at night, geese nap in the day. However domesticated a goose, its wakefulness and its atavistic alertness to danger has not been bred out of it.

Their alliances within a flock, their bouts of aggression and spells of passivity, their concentration, their impulsive, low, skidding flights when they have a whole meadow to use as a runway, the way they stand their ground against dogs or humans—these are all wonders. I find them so remarkable, I would not dream of eating a goose or selling a bird to anyone who would eat it, though I sometimes entertain the fantasy of a goose attacking a gourmet and eating his liver.

There are many more wonders: the way they recognize my voice from anyone else shouting and how they hurry near when called; or follow me because they know I have food in my bulging hand. They will follow me 300 yards, looking eager and hungry. I have mentioned their inexhaustible curiosity—sampling every plant that looks tasty, as well as pecking at objects as though to gauge their weight or their use. Their digestive system is a marvel—almost nonstop eating and they never grow fat (Why Geese Don't Get Obese (And We Do) is a recent book on animal physiology); their ability to drink nothing but muddy water with no obvious ill effects; and with this their conspicuous preference for clean water, especially when washing their heads and beaks, which they do routinely. Their calling out to a mate from a distance, and the mate rushing to their side; or if one becomes trapped under a steepness or enmeshed in a fence, and sounds the faint squawk of helplessness, the other will stay by, until it is released. Their capacity to heal seems to me phenomenal—from a dog bite, in the case of one gander I had that was at death's door for more than a month, or from the bite of another gander in one of their ritual battles for supremacy. Such conflicts often result in blood-smeared breast feathers. Their ability to overcome internal ailments is a wonder to behold.

I had an old, loud China gander that was displaced by a younger gander—his son, as a matter of fact, who ended up with the old goose we named Jocasta. From the time of Adam, we humans have had an urge to name the birds of the sky and the beasts of the field. The old gander may have been defeated by the son, but he remained feisty. Then he became ill, got weak, ate very little, couldn't walk, sat only in shade and moaned. He was immobilized. I dissolved in water some erythromycin I got at the feed store and squirted it down his throat with a turkey baster, and added some more to his water.

Several weeks went by. He lost weight, but I could see that he was sipping from his dish. From time to time I carried him to the pond—he paddled and dipped his head and beak, but he was too weak to crawl out. Still he seemed to respond to this physiotherapy. After a month he began to eat. One morning, going out to give him more medicine, I saw that he was standing and able to walk. I brought him some food, and as I put the food in his dish he took a few steps toward me and bit me hard on the thigh, giving me a purple prune-size bruise. This is not an example of irony or ingratitude. It is goosishness. He was thankfully himself again.

Paul Theroux is working on a new travel book, which retraces the route of his bestselling The Great Railway Bazaar.