Long Overdue, the Bookmobile Is Back

Even in the age of the Kindle and the Nook, the library on wheels can still attract an audience

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/bookmobile-in-community-631.jpg)

Tom Corwin clearly recalls the day when, on a whim, he decided to buy and restore a classic bookmobile.

“The best ideas just happen to you,” says Corwin, a writer and musician whose boyish, intense enthusiasm is highly contagious. “A friend came to dinner, and showed me the ad. He was hoping to use the bookmobile to extend his home library—into his back yard. When he realized it wouldn’t fit, I had an idea: Get well-known authors behind the wheel of the bookmobile, taking turns on a drive across the country, talking about the books that have touched their lives. What a great way to remind people of our connection to the written word, and how powerful it can be.”

Corwin, who lives just north of San Francisco, picked up the vehicle in Chicago. Made by Moroney— a family-owned company in Massachusetts, and America’s last hand-builder of bookmobiles— the mobile library had just been retired after 15 years of travel. Its sturdy oak shelves had showcased more than 3,200 books.

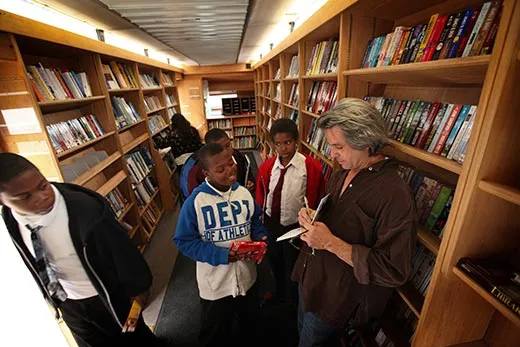

As Corwin navigated his new ride through the streets of Chicago, he was approached by an African-American man who asked if it was possible to peek inside. Bookmobiles, the man said, had been a fundamental inspiration while growing up in rural Mississippi in the mid-1960s. The public library had been closed to blacks—but the bookmobile stopped right on his street, a portal into the world of literature.

The gentleman was W. Ralph Eubanks: today an acclaimed author, and director of publishing for the Library of Congress.

“In contrast to the summer heat in south Mississippi, the bookmobile was frigid inside,” remembers Eubanks. “The librarians did not care that I was barefoot, and wearing a pair of raggedy shorts. All they cared about was that I wanted to read—and to help me find something I would enjoy reading.”

Eubanks’ story is just one example of the pivotal role bookmobiles have played in literary culture, and individual lives, for more than 150 years.

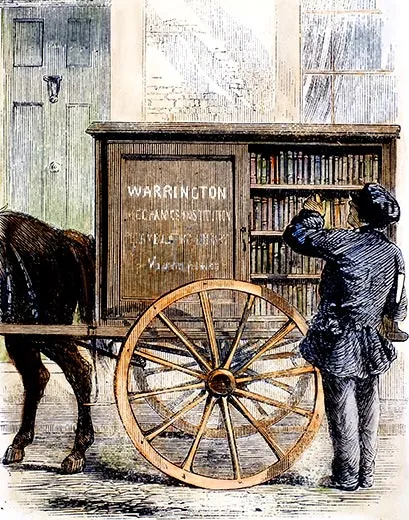

The first bookmobile seems to have appeared in Warrington, England, in 1859. That horse-drawn cart, a “perambulating library,” lent some 12,000 books during its first year of operation—a century before the sleek vehicle that would visit Arlington, Massachusetts, during my own elementary school years.

America’s first “traveling branch library” plied the county roads of Maryland, championed by visionary librarian Mary Titcomb. “Filled with an attractive collection of books and drawn by two horses,” wrote Titcomb, “with Mr. Thomas the janitor both holding the reins and dispensing the books, it started on its travels in April 1905.”

By the mid-20th century bookmobiles had become a part of American life, with more than 2,000 plying our inner cities and rural roadways. But shrinking budgets and rising costs have dimmed their prominence. Less than 1,000 bookmobiles now serve the continental U.S. and Alaska and they often show up in some unlikely places. The last bookmobile I encountered, before Tom Corwin’s, was parked at the sprawling Burning Man festival in the Nevada desert. A surprising number of celebrants were happy to forego the all-night revelry, and curl up instead with borrowed copies of Tender is the Night or The Yiddish Policeman’s Union.

Bookmobiles are still in service abroad. In at least three African and South American countries, camels and donkeys draw mobile libraries from town to town. Thailand drafts elephants into use, while Norway’s modern library ship Epos has served tiny coastal communities with its cargo of 6,000 volumes since 1963.

If Corwin realizes his vision, bookmobiles may slowly edge their way back into the mainstream. His planned documentary—Behind the Wheel of the Bookmobile—will feature interviews with renowned authors as they maneuver the Moroney across North America, giving away books donated by authors and publishers (http://bookmobiletravels.com/Home.html). To date more than 40 writers have signed on, including Amy Tan, Dave Eggers, Michael Chabon and April Sinclair. Author Daniel Handler, aka Lemony Snicket, was one of Corwin’s test pilots. He gleefully recalls his experience with a lumbering vehicle “full of books and shaky, like a writer's mind. The experience of driving it reminded me of trying to get a mountain to listen to reason.”

Writers who grew up with bookmobiles seem imprinted with a sense of gratitude, and unforgotten inspiration. “There was a bookmobile in Marin,” recalls Bird by Bird author Anne Lamott, “that you saw all the time. I have mystical dreamscape memories of climbing on board.”

Author and conservationist Terry Tempest Williams tells how she “waited with my brother for the bookmobile to come up our hill each Saturday. It was all part of the magic of our childhood, where books and natural history were all part of the same narrative of spending time outside.“

“The summer I turned eleven,” says Ralph Eubanks, “William Faulkner’s The Reivers came off the shelf of the bookmobile. It was the first book I read by a Mississippi author, the first hint that someone from my part of the world could also become a writer.”

These memories recall the era when a printed book was a precious thing. Today, the access once provided by bookmobiles is being usurped by iPads, Kindles and the Internet. The speed and convenience of these devices, combined with the staggering wealth of online content, makes them deeply seductive. With the digital revolution changing our reading habits, will bookmobiles become obsolete?

Tom Corwin believes not. “I sometimes read books on my iPhone,” he admits. “But there’s a different relationship with something made of pulp and ink. Books have a texture, a smell. There’s a sensual relationship with a book that we lose in the digital world.”

“It’s still a damn good technology,” agrees Ethan Canin, author of America, America. “If paper books continue to thrive, I think it will be for their practical qualities: light, cheap, not-likely-to-be-stolen, difficult to break, easily displayable -- and eminently lendable.”

But it’s not just about books. There’s also the human-to-human connection with bookmobile librarians, who steer and inspire their visitors’ reading patterns.

Though she agrees with Corwin and Canin, Martha Buckner—a bookmobile librarian in Ashland, Ohio since 2003—admits that the digital revolution is changing her audience. “While we serve members of all ages, we’ve began shifting our focus to preschools and daycares. We strongly believe that it is important that young children have a positive library experience, and that a book in every hand is crucial to promoting early literacy and future educational success.”

For Daniel Handler, who has written more than a dozen books for children, that “library experience” translates to a real-world adventure: a process of exploration and discovery that an e-reader can’t provide.

“In the digital world,” Handler observes, “searching is easy—and browsing is hard. The Internet can help you find what you're looking for, but a library finds you things you didn't even know you wanted. The bookmobile thus is a portable, wandering marvel, that searches you out in a world that more and more waits for you to search instead.”

“They’re traveling cathedrals of beauty and truth and peace,” Anne Lamott adds reverently. “A place where children can have access to all the great wisdom of the ages – from the deepest and most profound truths to the greatest belly-laughs.”

In late 2011, Tom Corwin hopes, his bookmobile will hit the road with a library of 3,000 old-fashioned books—along with a few donated e-book readers. Each technology has its pros and cons, and each must be a part of any conversation about literacy and learning. With any luck, Corwin’s beautifully restored Moroney 240-B will offer the best of both worlds.

Jeff Greenwald is the author of The Size of the World and Snake Lake.