Looking at the World’s Tattoos

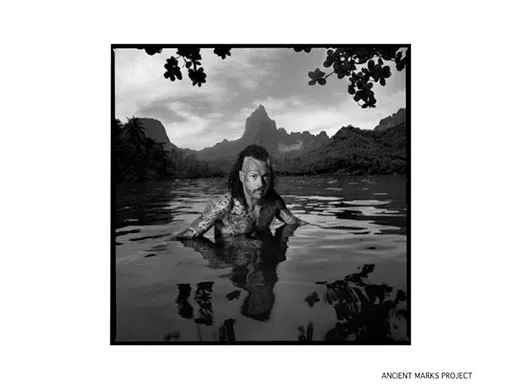

Photographer Chris Rainier travels the globe in search of tattoos and other examples of the urge to embellish our skin

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Body-Art-Dyaks-Ernesto-Kalum-631.jpg)

Chris Rainier has seen bare flesh etched by the crudest of implements: old nails, sharpened bamboo sticks, barracuda teeth. The ink might be nothing more than sugar cane juice mixed with campfire soot. The important part is the meaning behind the marks.

“Blank skin,” the photographer says, “is merely a canvas for a story.”

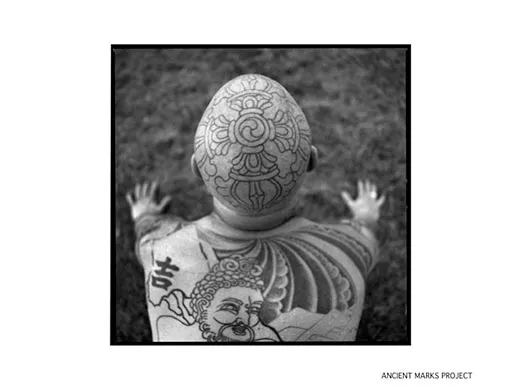

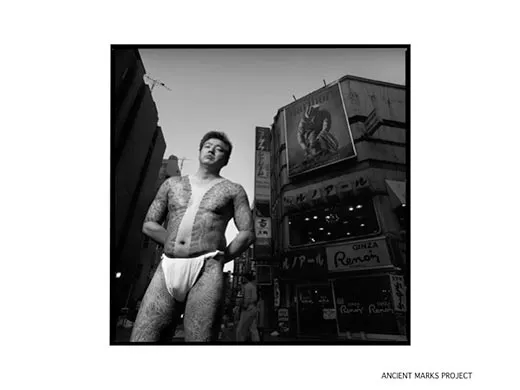

Rainier has documented these stories in dozens of cultures across the globe. In New Guinea, a swirl of tattoos on a Tofi woman’s face indicates her family lineage. The dark scrawls on a Cambodian monk’s chest reflect his religious beliefs. A Los Angeles gang member’s sprawling tattoos describe his street affiliation, and may even reveal if he’s committed murder. Whether the bearer is a Maori chief in New Zealand or a Japanese mafia lord, tattoos express an indelible identity.

“They say, ‘this is who I am, and what I have done,’” Rainier says.

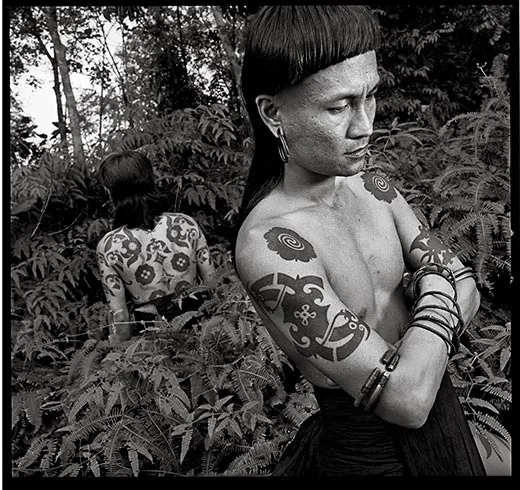

Rainier’s portraits are featured in a new film, Tattoo Odyssey, in which he photographs Mentawai people living in a remote village on the Indonesian island of Siberut. Their spider web-like tattoos, which echo the shapes and shadows of the forest, are meant to anchor the soul in the body and to attract benevolent spirits. The film premieres September 26th on the Smithsonian Channel.

Rainier’s images “lifted a veil on something that wasn’t accessible to us in Western culture,” says Deborah Klochko, director of San Diego’s Museum of Photographic Arts, which has displayed Rainier’s portraits. His work, much of it presented in the 2006 book Ancient Marks: The Sacred Origins of Tattoos and Body Marking, may be the most comprehensive collection of its kind, Klochko says. Yet, she points out, “he’s not an anthropologist. A scientist would take another kind of picture of the same markings. He brings a different sensibility, an emotional connection.”

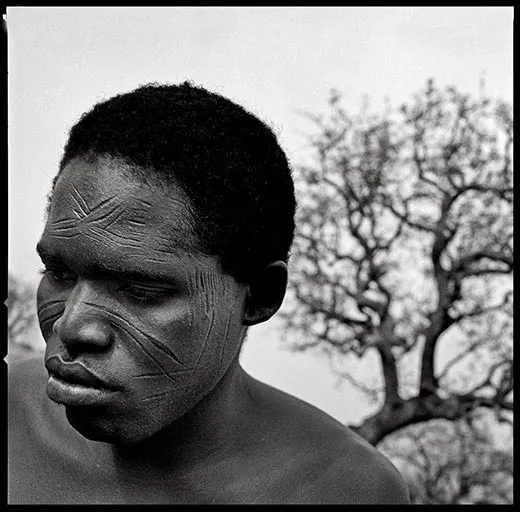

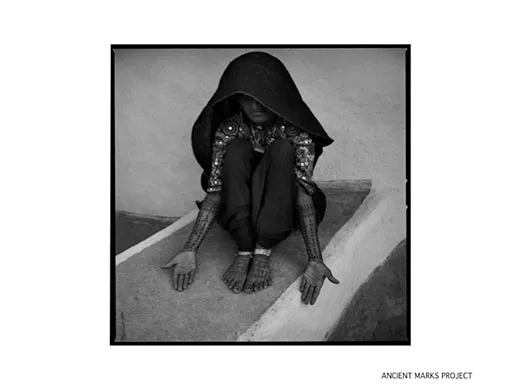

Rainier was Ansel Adams’ last assistant—they worked together in the early 1980s, until Adams’ death in 1984. Like his mentor, Rainier is primarily a black-and-white photographer. Unlike Adams, however, he is less captivated by landscapes than by the topography of the body, and he specialized in portraits. In the 1990s, while traveling the world to chronicle waning indigenous cultures, he got interested in traditional tattooing—which has cropped up from Greenland to Thailand at one time or another—and its sister art, scarification, a cutting practice more common in West Africa and elsewhere. Some of those customs, Rainier says, are dying out as modernization penetrates even remote areas.

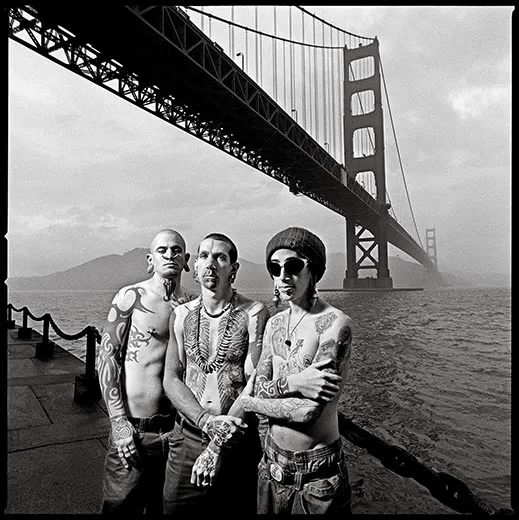

Yet he is also fascinated by the current tattoo craze in the United States, apparent everywhere from Nevada’s Burning Man art festival to Pacific Coast surf beaches to Midwestern shopping malls. Once confined to a few subcultures, tattooing has today gone mainstream: according to a 2006 Pew survey, 40 percent of Americans between the ages of 26 and 40 have been tattooed.

The modern West’s first recorded encounter with the Polynesian practice of tattowing dates from 1769, when Joseph Banks—a naturalist aboard the British ship Endeavour—watched a 12-year-old girl (the “patient,” he called her, though modern aficionados might prefer the term “collector”) being extensively adorned. Banks’ description is brief but harrowing: “It was done with a large instrument about 2 inches long containing about 30 teeth,” he wrote in his journal. “Every stroke...drew blood.” The girl wailed and writhed but two women held her down, occasionally beating her. The agony lasted more than an hour.

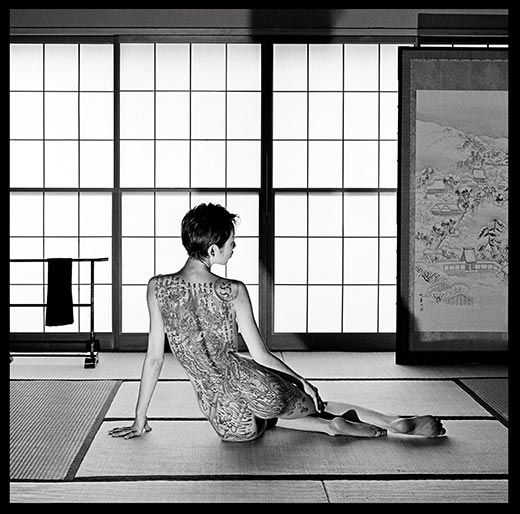

Yet sailors must have been intrigued. Soon they were returning from the South Pacific sporting tattoos of their own. The English recoiled (apparently unaware that ancient Europeans had also been devoted collectors), and as the colonial powers extended their reach around the globe, native people—often urged by missionaries—gradually began to relinquish their traditions, an abandonment that continues today. Back in Europe, tattoos were persistently associated with unruly sailors, although they did achieve a subversive glamour in certain circles: in the early 1900s, the future Marchioness of Londonderry tattooed a snake, a star and a coat of arms on her leg, and King George V boasted a Japanese-style dragon.

Today people are appropriating these ancient practices, Rainier believes, because they want to carve out an identity in a chaotic postindustrial age by inscribing shoulders and shins with symbols of love, death and belonging.

Even if a design has no literal significance, the act of tattooing is an initiation rite in itself. “A tattoo stood—and among many peoples still stands—for many things, including the ability to tolerate pain,” says Nina Jablonski, a Pennsylvania State University anthropologist and author of Skin: A Natural History. Sometimes, physical loveliness becomes inseparable from personal suffering. In West African nations like Togo and Burkina Faso, where scarification is common, Rainier would often ask to photograph the most beautiful man and woman in a given village. “Inevitably they would be the most scarred,” Rainier says. “You didn’t gain your beauty until you were scarred.”

Taken as art, tattoos unite disparate cultures, says Skip Pahl, who displayed Rainier’s photographs at California’s Oceanside Museum of Art. The images attracted an unusually diverse group of museumgoers: Samoan immigrants, surfers, gang members, U.S. Marines and devout Latinos, all of whom have their own tattoo aesthetic. The exhibition was accompanied by a runway show in which tattoo artists paraded their most exquisitely inked customers.

After visiting the Mentawai last year—a trip previously thwarted by security concerns after September 11, 2001, and by the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami—Rainier says his tattoo portfolio is at last complete. His own epidermis remains thus far unimproved, but that’s about to change: “I said to myself once the project is over and done that I will pick an artist and a design,” he says. “I’m at that point now.”

Having spent 20 years exploring the power and permanence of tattoos, however, he’s finding the selection very difficult: “We live in a culture where everything is disposable, and it’s like, ‘wow, that’s forever.’ ”

Abigail Tucker is the magazine’s staff writer. Photographer Chris Rainier is working on a book about traditional masks.