Loving Elephants, the Meaning of Life, a London History and More Recent Books

A pioneering elephant rescuer looks back on the loves of her life and a collection of essays investigates the history of happiness

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Books-Saving-Grace-631.jpg)

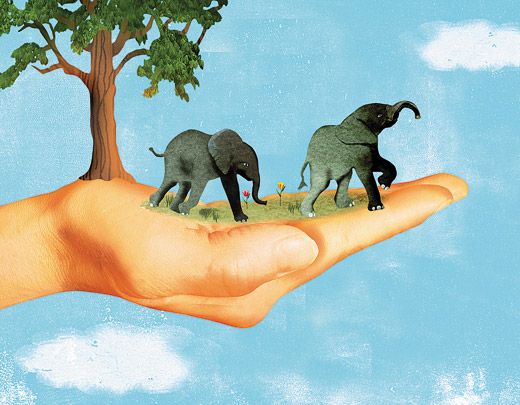

Love, Life, and Elephants: An African Love Story

by Daphne Sheldrick

If Dame Daphne hadn’t already been honored by the Queen of England, I would personally lobby on her behalf. This extraordinary woman has saved hundreds of orphaned baby elephants left parentless by poachers, as well as baby rhinos, gazelles and other African animals. Her memoir begins with the arrival of her ancestors in Africa in the 1820s and ends with her current daily routine: Nearing 80, she’s up at dawn making sure the creatures at her Nairobi National Park nursery have made it through the night, checking in with her 50 elephantkeepers, supervising the elephants’ bottle-feedings and mud baths. As if that wasn’t enough, she can write, too.

Just one example of the characters she introduces to turn her readers to goo: a newborn calf named Gulliver, who had “the hairy wizened look of a little old gnome.” To nurse him, Sheldrick crouched under a fully grown matriarch, substituting a bottle for the matriarch’s dry teat. Gulliver didn’t make it and was intensely mourned—most of all by his “nanny,” an older elephant named Sobo, who visited Gulliver’s burial site each evening to pay her respects to her little charge. There are times when the responsibilities must have been too much. “Animals weave their way into one’s heart so completely,” writes Sheldrick, “that each death is a painful bereavement.” By the 1960s, she had earned a reputation as the best, perhaps the only, person who could give abandoned elephants a shot at life. The infant animals kept coming, and she kept taking them in.

This is a love story on another level, delving into Sheldrick’s passion for her late husband, David Sheldrick, a warden for Kenya’s Tsavo East National Park, a valiant foe of poachers and a conservationist well ahead of his time. Sheldrick’s passion for her husband is clear—her charity bears his name—but her love for the African wildlife and all the creatures that aid her quest to make the world a more humane place is the more striking. Perhaps Sheldrick’s most extraordinary assistant is Eleanor, an elephant found in 1961 at age 2. She was paraded before agricultural fairs—becoming morose and obese—before arriving at the Sheldricks’ refuge. There she became a surrogate mother; once Sheldrick had weaned the infants, Eleanor would take over, teaching the elephants how to be elephants. Their partnership lasted more than 30 years, until Sheldrick and her colleagues returned Eleanor to the wild—a crowning cap to an incredible career.

The Mansion of Happiness: A History of Life and Death

by Jill Lepore

This essay collection by the Harvard historian takes its title from a wildly popular 19th-century board game that schooled players in the virtues. Do “not even think of Happiness,” the instructions said, if you possess “AUDACITY, CRUELTY, IMMODESTY, or INGRATITUDE.” This game and its later incarnations, writes Lepore, aren’t just child’s play; they pose “questions about the meaning of life.” So do Lepore’s essays, some of which have been published in the New Yorker. When did we start to think of fetuses as humans? Who was the first person to take cryogenics seriously? How has the perception of breast-feeding evolved? This is a slow read, but in the best way; each sentence brims, each paragraph delights. Taken together these essays are more than the sum of their parts. They are an inquiry into how we think about being alive. I’m hard-pressed to name a scholar who is better able to skim the centuries without sacrificing seriousness.

Johnson’s Life of London: The People Who Made the City That Made the World

by Boris Johnson

Almost everyone I know who lives in London has a story about seeing the mayor, the author of this chummy, chatty history of that great city. (My husband saw Boris once—everyone calls him Boris—when we lived in London. His excitement was met with yawns from our British friends.) It helps that the mayor has a head of perpetually disheveled platinum hair and really does rely, it seems, on the bicycles he champions as a superior means to get about the city. Boris is no Michael Bloomberg, the New York City mayor, who poses for the cameras on the subway while his chauffeured SUV waits at the next stop. Boris is on the streets, engaged with the city’s grit and—as his new book shows—history. A journalist before he went into politics, he has a flair for describing personalities. Samuel Johnson is “the great harrumphing voice of political incorrectness.” The pope, emerging from an Alitalia jet, glows “like a sugared almond.” Keith Richards is a “kohl-eyed demigod” with “a face as lined as Auden’s.”

Swimming Studies

by Leanne Shapton

No tales of triumph here—but don’t let that dissuade you from this subtle, spare and elegant meditation on the physical and psychic torments, not to mention satisfactions and joys, of extreme athletic discipline. A world-class swimmer, Shapton qualified for the Canadian Olympic trials as a teenager but is known today as a whimsical writer and visual artist, author of the charming Important Artifacts and Personal Property from the Collection of Lenore Doolan and Harold Morris, Including Books, Street Fashion, and Jewelry, best described as a novel in scrapbook form. She uses a similar collage-style approach here, including paintings of pools in which she has swum, lists of smells associated with her chlorine-suffused youth, photographs of bathing suits she has worn and loved. In this fascinating plunge into the world of competitive swimming, she isolates the poignant moments: the pain of icing her knees, a teammate’s steamy silhouette as she opens the door to the frozen parking lot. Anyone who has entertained thoughts of extraordinary physical feats, only to accept the limits of one’s body, will recognize the moving struggles that Shapton captures.

Up on the Roof: New York’s Hidden Skyline Spaces

by Alex MacLean

The New York City rooftop is perhaps the most rarified space in the American landscape—a precious plot, high above the fray, but still connected to the hustle and bustle below. Skyscrapers can be built layer upon layer, multiplying available square footage, but rooftop acreage will never exceed the footprint of the city. Swooping through the New York City airspace, Massachusetts-based photographer and pilot Alex MacClean snapped stunning shots of this usually invisible landscape, revealing a kind of “floating city” as architect Robert Campbell puts it in his introduction. We’re voyeurs when we look at these photos; there’s a woman sunbathing topless, another gardening in his shorts, clusters of young beautiful things sipping cocktails. But the photos shine in less risqué ways as well. Fields of mature vegetation on the tops of tony old apartment buildings make up an urban canopy. Basketball courts, putting greens, and plastic blow-up swimming pools reveal an elevated playground for children of all ages. These pictures allude to the millions of lives lived below—the hidden drama of the city—but they are also visually striking in their own right, an aerial patchwork of widely varying worlds.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/books-chloe-schama-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/books-chloe-schama-240.jpg)