Man Ray’s Signature Work

Artist Man Ray mischievously scribbled his name in a famous photograph, but it took decades for the gesture to be discovered

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Man-Ray-artist-631.jpg)

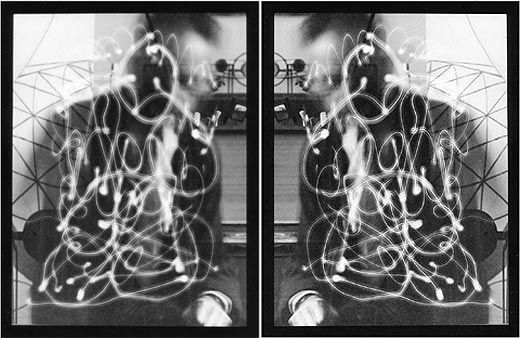

In 1935, the avant-garde photographer Man Ray opened his shutter, sat down in front of his camera and used a penlight to create a series of swirls and loops. Because of his movements with the penlight, his face was blurred in the resulting photograph. As a self-portrait—titled Space Writings—it seemed fairly abstract.

But now Ellen Carey, a photographer whose working method is similar to Man Ray’s, has discovered something that has been hidden in plain sight in Space Writings for the past 74 years: the artist’s signature, signed with the penlight amid the swirls and loops.

“I knew instantly when I saw it—it’s a very famous self-portrait—that his signature was in it,” says Carey, a photography professor at the University of Hartford. “I just got this flash of intuition.” Her intuition was to look at the penlight writing from Man Ray’s point of view—which is to say, the reverse of how it appears to anyone looking at the photograph. “I knew that if I held it up to a mirror, it would be there,” Carey says. She did, and it was.

“This makes perfect sense if you understand that throughout his career, Man Ray did many artworks based off his signature,” says Merry Foresta, who curated a 1988 exhibition of his work at the National Museum of American Art (now the Smithsonian American Art Museum) and decorates her Washington, D.C. office with a poster of his iconic Tears image.

Man Ray’s mischievous gesture is typical of his work. He was born Emmanuel Radnitsky in Philadelphia in 1890, but he spent most of his youth in the Williamsburg section of Brooklyn. In 1915, he met Marcel Duchamp, who introduced him to the modern art scene; the pair were involved with the Dadaists, who rejected traditional aesthetics (Duchamp, for example, displayed a urinal titled Fountain as part of his readymades series), and, later, the Surrealists.

In 1921, Man Ray left for Paris, joining Duchamp and serving as the unofficial photographer for the city’s art elite, including Pablo Picasso and Salvador Dali. When the Nazis invaded Paris in 1940, Man Ray left for Hollywood, where he worked as a fashion photographer. He returned to Paris in 1951 and created photographs, paintings, sculptures and film until he died, at age 86, in 1976.

It was in his early years in Paris that he developed a technique for creating photographic images by placing objects directly on light-sensitive paper and then exposing the assemblage to light. “Rayographs,” he called them. Although he often included images of hands—main, the French word for “hand” is pronounced like men with a swallowed ‘n’—and other symbolic references to his name, Space Writings is one of only a few works in which he is known to have left a literal signature.

He created the image around the time he was preparing to return to New York for “Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism,” a 1936 exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art. This was the first exhibition to bring Dadaist and Surrealist art to the United States, and it included many of his works. Foresta, director of the Smithsonian Photography Initiative, speculates that he was hoping the show would provide a great re-entry into his home country—but also worrying about leaving the city that had become his artistic home. “This was really a turning point in his career,” she says. “He was about to lose his identity as an important artist.”

Adding his signature to Space Writings, she says, might have been his way to declare himself to a new audience.

But it’s still not clear why he chose to have the writing reversed in the image. “I think it mattered to Man Ray to be known as a mysterious inventor, an alchemist,” Foresta says. “He can see it, but to us, it’s still an abstract image.”

She and Ellen Carey have known each other for 20 years; Carey’s work has been exhibited in museums around the world, and the Smithsonian Institution holds some of her work in its collection. When Foresta stopped by Carey’s studio for a visit last year and saw Carey working with penlights, she suggested that Carey take a look at Space Writings because of the similarity in technique. That suggestion led to Carey’s discovery.

Foresta says she thinks Carey was uniquely qualified to find the signature because she looks at Man Ray’s work from the point of view of a practicing artist, rather than as an art historian. And like Man Ray, Carey creates images that focus on the photographic process rather than on realistic representations. (In her best-known series, “Pulls,” she literally pulls film through a large-format Polaroid camera to create streaks of color.) “You really need to look at the object, and the object will talk to you or stare back,” Carey says. “I think it was just a matter of looking.”

It might have taken seven decades and a like-minded photographer to see the disguised signature, but the evidence is clear. “Oh, it’s definitely there,” Carey says. “It’s saying, ‘Hello, how come no one noticed for 70 years?’ I think [Man Ray] would be chuckling right now. Finally, somebody figured him out.”

Her discovery will be cited in the catalogue for the Jewish Museum’s exhibition Alias Man Ray: The Art of Reinvention, opening November 15 in New York City.