Mark Catesby’s New World

The artist sketched American wildlife for Europe’s high society, educating them on the creatures living among the unexplored lands

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/catesby_631.jpg)

It is no secret that the 18th-century British natural history artist Mark Catesby occasionally copied the work of his predecessors. His sketch of a land crab bears a striking resemblance to a watercolor rendered by John White (see "Brave New World" in the December SMITHSONIAN), a British artist who joined Sir Walter Raleigh's voyages to present-day North Carolina in the 1580s. The crustacean's spiny legs are bent at all the same angles as they are in White's version.

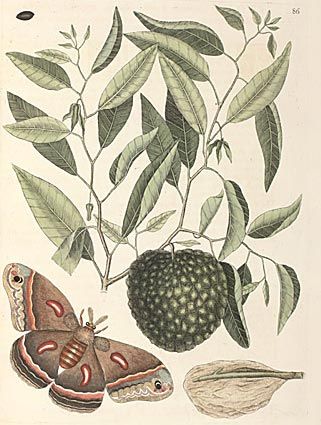

In total, Catesby replicated, possibly even traced, about seven of White's published watercolors. The patchwork of amorphous spots on his puffer fish is virtually identical to White's, and he acknowledges White as the source for his stunning illustration of a tiger swallowtail butterfly. The borrowing of images was quite common at the time. Naturalists viewed their collected works as encyclopedias and were willing to include entries originally authored by others for the sake of being comprehensive. In Catesby's case, scholars suspect that he copied others' illustrations in the rare instances when he hadn't observed the creature on his own or hadn't been in the position to sketch it.

"As an empiricist, Catesby believed that drawings by other naturalists offered him direct access to their own first-hand observations of the natural world," explains Amy Meyers, a Catesby scholar and the director of the Yale Center for British Art in New Haven, Connecticut.

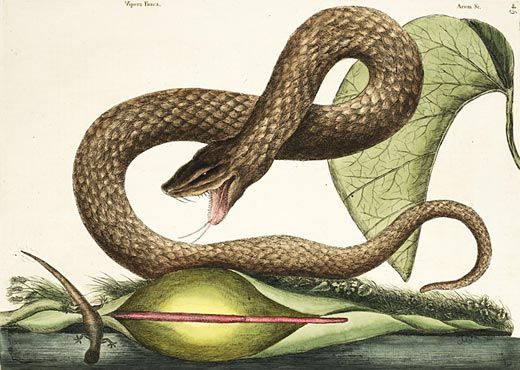

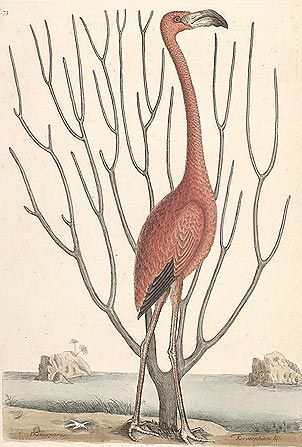

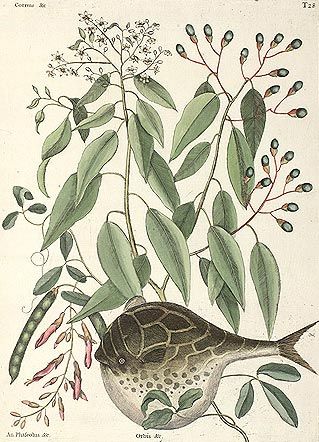

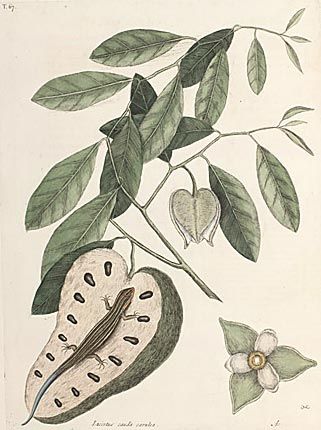

Copies aside, Catesby was innovative in the way he presented his comprehensive survey of the flora and fauna of America's colonies in his Natural History of Carolina, Florida, and the Bahama Islands. While most of his predecessors' illustrations were of birds mounted on dead stumps or ducks bobbing on a shallow strip of water, Catesby's, mostly drawn from life, were some of the first to depict environmental relationships—a bead snake wrapped around the potato root that it's often dug up with or a blue jay shown with the berries it eats.

When Catesby translated his copied drawing of White's land crab into an etching, he added a small branch bearing a dangling fruit, clasped in the crab's claws. In doing so, Catesby created "a study of organic interaction," writes Meyers. "The naturalist thus transformed a traditional specimen drawing into a composition reflecting his own observations of the way in which two species interrelate in their shared habitat." In some cases, however, which Meyers points out are "the exception rather than the rule," Catesby pictured a plant and animal together purely for aesthetic reasons.

Many natural history artists before him drew from specimens carried back to Europe by sailors and diplomats who could only provide the country or region of their origin. But Catesby's etchings often provided information about what an animal feeds on or what plants and animals are found in the same environs—information he could only have attained by immersing himself in his subjects' habitats. Catesby was 29 when he made his first trip to the American colonies in 1712. He stayed with his sister, who was living in Williamsburg, Virginia. Not much is known about his training as a naturalist or artist. Some suspect that British naturalist John Ray and Ray's colleague, botanist Samuel Dale, who Catesby would have known through family connections, may have mentored him. But he explored the Virginia landscape, unsponsored and largely on his own, collecting leaves and seeds and sketching his findings as he followed rivers from settlements to the wilder woods around their sources. After seven years, he returned to England, where members of the Royal Society of London had begun to take interest in his drawings. One member offered him a salary "to Observe the Rarities of the Country for the uses and purposes of the Society," and in 1722 Catesby traveled to Carolina. In the four years he spent there and in Florida and the Bahamas, he combed the fields, forests, swamps and shores for wildlife. He painted watercolors in the field; recorded details such as an animal's coloring, where it was seen and any additional information natives provided; and shipped specimens back to his Royal Society patrons, who often planted his exotic seeds in their gardens.

Soon after returning to London in 1726, Catesby etched his drawings onto copper plates, often combining two different sketches into one to create his engaging and informative compositions. He organized the 220 etchings into two volumes—the first featured birds and plants and the second included fish, insects, reptiles, amphibians, mammals, and the plants associated with them—and decided he would release them in 20-plate installments. With subscribers, many from the upper echelon of society, wanting some 180 copies, he had to hand color close to 40,000 prints. The endeavor amounted to nearly 20 years of labor and literally became his life's work. Catesby died, in 1749, just two years after its completion.

I recently visited the Smithsonian Institution's Cullman Library, a temperature- and humidity-controlled room in the bowels of the National Museum of Natural History that contains two of the estimated 80 to 90 remaining original copies of Catesby's Natural History. Leslie Overstreet, the library's curator of natural-history rare books, pulled from the shelves a classic encyclopedia of animals from the 1560s, a book of John White's watercolors, a major anthology of birds by Catesby's contemporaries and, of course, Catesby's Natural History. Thumbing through the books, I could see the progression from isolated specimens on sterile white backdrops to animals artistically framed by their natural settings. I became acutely aware of the vitality in Catesby's etchings—a blue jay's beak open in mid-song, a viper hissing, a playful lizard hanging from a stalk of sweet gum, a kingfisher slurping down a fish—and I was not surprised when Overstreet said, "It was the book for about a hundred years."

After all, Cromwell Mortimer, secretary of the Royal Society and former owner of one of the Smithsonian's copies, hailed it as "the most magnificent work I know since the Art of printing has been discovered." Carolus Linnaeus named Catesby's trillium, Catesby's lily and Catesby's pitcher plant, as well as Rana catesbeiana, the North American bullfrog, in the naturalist's honor. Not to mention, artist John James Audubon's paintings, done more than a century later, were a natural extension of Catesby's illustrations.

Audubon eventually became the more remembered of the two wildlife artists, but in the last decade, there's been something of a Catesby revival. His appeal has broadened among academics, for one. Overstreet says that the researchers who visit the library to see Catesby's Natural History are split almost evenly between those studying it for its scientific value and those studying it for its artistic value. And there has been a push to increase public awareness of the artist. In 1997, 50 of Catesby's original watercolors, previously owned by King George III, toured America for the first time. This past summer, the Smithsonian Institution Libraries hosted "Mark Catesby's America," a symposium featuring experts who approached the artist and his work from the perspectives of science, art and history. The 2007 documentary "The Curious Mister Catesby" was shown at the symposium and now its producers will be encouraging public television networks to air it on Earth Day in April. An exhibition titled "Catesby, Audubon, and the Discovery of a New World" opens December 18 at the Milwaukee Art Museum. And following the example of a few other institutions, Smithsonian Libraries will be creating a digital copy of Natural History for inclusion on an all-Catesby Web site to be launched next year.

Adding an element of poignancy to Catesby's story is the fact that several of the species he depicted (the parrot of Carolina, the largest white-billed woodpecker and the greater prairie chicken) are now extinct and others (the hooping crane, flying squirrel and wood pelican) are endangered.

"We must look closely at how well 18th-century Colonial naturalists in the trans-Atlantic world understood that the project of empire was setting into motion new patterns of organic interaction, since it involved not only the movement of people, but other living organisms from across the globe," says Catesby scholar Meyers. "Catesby understood that radically new organic relationships were being established that would remake this New World in highly significant ways."

Surely there's a lesson to be learned in his passion.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)