Mark Twain in Love

A chance encounter on a New Orleans dock in 1858 haunted the writer for the rest of his life

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Mark-Twain-Laura-Wright-631.jpg)

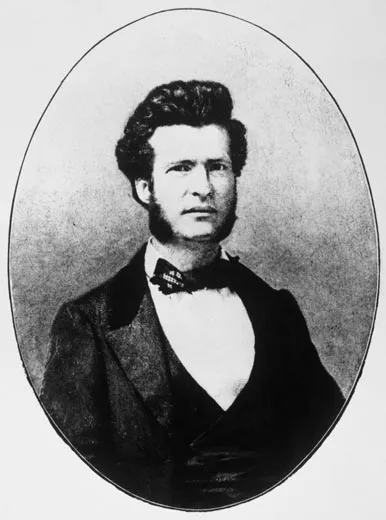

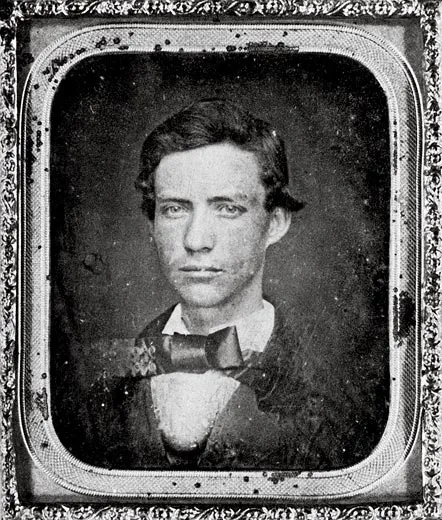

On an empyreal spring evening in 1858, with the oleander in bloom upriver and early jasmine scenting the wind, the steersman for the Mississippi steamboat Pennsylvania, a bookish 22-year-old named Sam Clemens, guided the massive packet into the docks under the winking gaslights of New Orleans. As the Pennsylvania berthed, Clemens glanced to his side and recognized the adjacent craft, the John J. Roe.

Perhaps recalling his many happy assignments steering the Roe, the young apprentice pilot leapt spontaneously onto the freighter’s deck. He was amiably shaking the hands of his former mates when he froze, transfixed by the sight of a slight figure in a white frock and braids: a girl not yet on the cusp of womanhood who would forever after haunt his dreams and shape his literature.

Mark Twain’s description, written years later, of the girl as she emerged from the jumble of deckhands, leaves no doubt as to the spell she cast on him. “Now, out of their midst, floating upon my enchanted vision, came that slip of a girl of whom I have spoken...a frank and simple and winsome child who had never been away from home in her life before.” She had, the author continued, “brought with her to these distant regions the freshness and the fragrance of her own prairies.”

The winsome child’s name was Laura Wright. She was only 14, perhaps not quite, on that antebellum May evening, enjoying a river excursion in the care of her uncle, William C. Youngblood, who sometimes piloted the Roe. Her family hailed from Warsaw, Missouri, an inland hamlet some 200 miles west of St. Louis.

She surely could never have imagined the import of that excursion. In this centenary year of Mark Twain’s death, it may seem that literary detectives have long since ransacked nearly every aspect of his life and works. Yet Laura Wright remains among the final enigmas associated with him. Only one faded photograph of her is known to exist. All but a few fragmentary episodes of her own long life remain unchronicled. Mark Twain’s references to her are, for the most part, cryptic and tinged with mysticism. Their encounter in New Orleans spanned but parts of three days; they met only once after that, in a brief and thwarted courting call that Sam paid two years later in 1860.

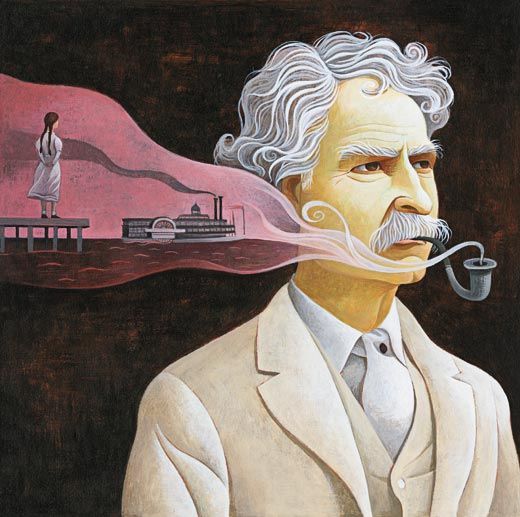

Yet in a powerful, psychic sense, they never parted. In 1898, Mark Twain,at the time living in Vienna with his wife, Olivia Langdon Clemens (Livy), and daughters Susy, Clara and Jean, finally unburdened himself of Laura Wright’s impact on him. In a lengthy essay entitled “My Platonic Sweetheart,” published posthumously in 1912, he described a protracted and obsessive recurring dream. A young woman appeared, with differing features and names, but always under the guise of the same benevolent, adoring persona. Mark Twain and the mysterious apparition floated hand in hand over cities and continents, spoke a language known only to themselves (“Rax oha tal”), and comforted each other with a love more rarefied than between brother and sister, yet not specifically erotic. Mark Twain did not supply the specter’s real-life name, but scholar Howard Baetzhold has pieced together overwhelming evidence that the figure in the dream is Laura.

The Platonic Sweetheart gazes out at us today, Mona Lisa-like, from her repose inside the fecund dream world of the man who redefined American literature. But how significant was Laura Wright’s influence on Mark Twain, both as an object of affection and as a muse? Mark Twain took the answers to these questions with him when he joined the arc of Halley’s comet at Redding, Connecticut, on April 21, 1910. Yet Baetzhold’s investigations—not to mention Mark Twain’s own writings—have generated powerful evidence that the effect of this nearly forgotten figure was profound.

Certainly Mark Twain’s obsession arose instantaneously. In his posthumously published Autobiography he recalled losing no time declaring the young girl to be his “instantly elected sweetheart” and hovering no more than four inches from her elbow (“during our waking hours,” the Autobiography primly stipulated) for the ensuing three days. Perhaps he escorted her along the colorful French market or danced the schottische on the deck of the Roe. The two talked and talked, their conversations drifting unrecorded into the ether.

Never mind her tender years and provincial origins; something about Laura Wright seared itself into Sam’s soul. “I could see her with perfect distinctness in the unfaded bloom of her youth,” Mark Twain went on in his Autobiography, “with her plaited tails dangling from her young head and her white summer frock puffing about in the wind of that ancient Mississippi time.”

Sam and Laura were obliged to part when the Pennsylvania backed out of the docks for its upriver voyage. Laura had given him a gold ring, Mark Twain would many years later confide to his secretary, Isabel Lyon. Only three weeks later, a catastrophe occurred, as traumatic to Sam as meeting Laura had been rhapsodic. This tragedy may have forged his need to take recourse from grief in fantasies of a healing angel. On the morning of Sunday, June 13, the Pennsylvania exploded, with tremendous loss of life. Sam was not aboard, but his younger brother, Henry, was—serving as a “mud clerk,” or boy who would go ashore, often at a mud bank, to receive or hand off freight. Sam had secured the position for his brother as a gift, hoping to offer the shy boy an exposure to Sam’s own world of riverboat adventure. It took the badly burned Henry a week to die in a makeshift Memphis hospital. Sam reached his brother and witnessed the end. The guilt-ridden letter in which he announced the news to the Clemens family amounts to a scream of primal anguish. “Long before this reaches you,” it began, “my poor Henry—my darling, my pride, my glory, my all, will have finished his blameless career, and the light of my life will have gone out in utter darkness. O, God! this is hard to bear.”

As Sam mourned his brother, Laura Wright remained fixed in Sam’s memory. He wrote letters to her, which she answered; in 1860 or so, he traveled to the family home in Warsaw to court her. Laura’s mother, no doubt suspicious of the 24-year-old riverman’s intentions toward her 16-year-old darling, may have pried into some of those letters—although years later, an aging Laura denied this to Mark Twain’s first biographer, Albert Bigelow Paine. At any rate, Mrs. Wright treated Sam with hostility; he soon stormed off in a fit of his famous temper. “The young lady has been beaten by the old one,” he wrote to his older brother Orion, “through the romantic agency of intercepted letters, and the girl still thinks I was in fault—and always will, I reckon.”

After he departed Warsaw, Clemens went so far as to consult a fortuneteller in New Orleans, one Madame Caprell, from whom he sought the lowdown on his prospects for rekindling the romance. (Clemens may have had his doubts about the existence of God, but he was a pushover for the paranormal.) Mme. Caprell “saw” Laura as “not remarkably pretty, but very intelligent...5 feet 3 inches—is slender—dark-brown hair and eyes,” a description that Clemens did not refute. “Drat the woman, she did tell the truth,” he complained to his brother Orion in an 1861 letter, after telling him that the medium had placed all blame on the mother. “But she said I would speak to Miss Laura first—and I’ll stake my last shirt on it, she missed it there.”

Thus it was Sam’s stubbornness that foreclosed any further encounter with Laura Wright. Yet they did meet, time and again, over the years, in Clemens’ dreams. And dreams, Samuel Clemens came to believe, were as real as anything in the waking world.

It is impossible to know when the Laura visitations commenced, but mention of them is strewn across the decades of Mark Twain’s writing. He thought of “Miss Laura” when he went to bed at night, he had admitted to Orion in that 1861 letter. At some point the thoughts morphed into nocturnal visions. “Saw L. Mark Write in a dream...said good bye and shook hands,” he wrote in his notebook in February 1865 from California, carefully altering her true name, as he always did. Mark Twain had already somehow discovered that the “instantly elected sweetheart” had elected someone else. “What has become of that girl of mine that got married?” he wrote in a letter to his mother, Jane Clemens, in September of 1864. “I mean Laura Wright.”

This was the period of Sam Clemens’ wild self-exile in the West, to which he had repaired with Orion to escape the Civil War. His robust drinking, alternating moods of risk-taking, pugnacity and black despair (he wrote later of placing a pistol barrel to his head but not squeezing the trigger), his crude practical jokes and his pose of flamboyance (“I am the most conceited ass in the Territory”) pointed to demons as disturbing as the prospect of death on the battlefield. Sorrow and guilt over Henry’s fate ravaged him—Mark Twain revisited the tragedy many times in his writing. As his letter to Jane Clemens shows, Laura weighed on his mind as well.

The corporal Laura weighed, that is. In her dream version, she had the opposite effect. The Platonic Sweetheart was weightless, serene: angelic, in fact—a healing angel to the troubled sleeper. “I put my arm around her waist and drew her close to me, for I loved her...my behavior seemed quite natural and right,” Mark Twain wrote in “My Platonic Sweetheart” of an early dream encounter. “She showed no surprise, no distress, no displeasure, but put an arm around my waist, and turned up her face to mine with a happy welcome in it, and when I bent down to kiss her she received the kiss as if she was expecting it.” Mark Twain continued: “The affection which I felt for her and which she manifestly felt for me was a quite simple fact; but....It was not the affection of brother and sister—it was closer than that...and it was not the love of sweethearts, for there was no fire in it. It was somewhere between the two, and was finer than either, and more exquisite, more profoundly contenting.”

It is possible that the dream-Laura might have counterweighted the demons that roiled in Mark Twain’s legendary “dark side,” as he called it, out West, tempering their self-destructive power over him, even as their fury ignited his creative fires. It was in the West, after all, that the “jackleg” (or self-improvised) journalist Mark Twain—he took the pseudonym in 1863—fully surrendered to the writing life and began to perfect the hot, lean, audacious, shockingly irreverent “voice” that would soon liberate American letters from the ornate pieties of the Boston Brahmins and, behind them, Old Europe. His editor at the Virginia City (Nevada) Territorial Enterprise, Joe Goodman, declared in 1900 that Mark Twain wrote some of the best material of his life—most of it alas, lost—during those Western years. “I was...fighting off lawsuits continuously,” Goodman recalled. “Nevertheless I stayed with Sam and never so much as cut a line out of his copy.”

A Laura-like apparition visited Clemens’ dreams at intervals throughout the rest of his life. He alluded to their fleeting waterfront romance in his notebooks and in his Autobiography. Baetzhold believes that Laura was the model for Becky Thatcher in The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, for Laura Hawkins in The Gilded Age, for Puss Flanagan in A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court and even for Eve in “Eve’s Diary,” a comical short story based on the biblical creation myth. Except for Becky, these figures are among the most vibrant and autonomous female characters created by a writer often criticized for his one-dimensional, desexualized women. And Becky, that “lovely little blue-eyed creature with yellow hair plaited into two long tails, white summer frock and embroidered pantalettes,” comes strikingly close to that winsome child “with her plaited tails dangling from her young head and her white summer frock puffing about in the wind.”

Finally, in 1898, Mark Twain addressed Laura Wright straight on in all her dimensions, although not by name. “My Platonic Sweetheart” chronicled her appearances in dreams over the years. The essay was not published in Harper’s magazine until two and a half years after Mark Twain’s death.

But what of Laura Wright herself?

Details of her life after New Orleans are sparse, but they suggest a woman of exceptional grit and resilience—and bad luck. Mark Twain wrote in his Autobiography of a letter from Laura, detailing her own crisis as she traveled upriver in May 1858. The Roe hit a snag and took on water; its passengers were evacuated, but Laura insisted to the captain that she would not leave her cabin until she had finished sewing a rip in her hoop skirt. (She calmly completed her task and only then joined the evacuees.) Shortly after that misadventure, according to a family friend, C. O. Byrd, she signed on as a Confederate spy and ended up with a price on her head. During the Civil War, she married a river pilot named Charles Dake, perhaps to escape the dangers of life as an espionage agent. She and her new husband headed west.

In San Francisco, Laura opened a school for “young ladies” and attained some sophistication. A tantalizing question is whether Laura was in the audience at Maguire’s Academy of Music in San Francisco on the night of October 2, 1866. There, Mark Twain delivered a vivid and uproarious account of his interlude as a Sacramento Union reporter in the Sandwich Islands—present-day Hawaii. The performance launched him as one of the country’s most celebrated lecturers in an era when traveling speakers from the droll Artemus Ward to the august Ralph Waldo Emerson bestrode the popular culture.

She moved to Dallas and became a public-school teacher. In March 1880, the 44-year-old Sam Clemens (by then happily married to Livy—whom he had wed in February 1870) opened a letter sent to his residence in Hartford, Connecticut, by a 12-year-old Dallas schoolboy with the wonderful name Wattie Bowser. Wattie asked the great man to answer biographical questions for a school essay, then added a stunning postscript:

“O! I forgot to tell you that our principal used to know you, when you were a little boy and she was a little girl, but I expect you have forgotten her, it was so long ago.” The principal’s name was Laura Dake—nee Wright. Writing to Laura through Wattie, Clemens sent back a torrential series of letters, filled with lyrical allusions to his youth and assuring Wattie/Laura, “No, I have not forgotten your principal at all. She was a very little girl, with a very large spirit...an unusual girl.”

One of the last known communication between Clemens and Laura occurred 26 years later. Laura, then 62, was teaching at poverty-level wages. Even so, she was trying to help a young man—perhaps he had been one of her students—who needed money to attend medical school. She asked her former suitor to intercede for her with the philanthropist Andrew Carnegie. Clemens recognized the thinly disguised plea for help and sent her a check for one thousand dollars. She sent a letter of thanks. A few additional letters were exchanged the following year.

Laura re-emerges one final time, some 15 years after Mark Twain’s death. According to a letter written in 1964 to scholar Charles H. Gold by C. O. Byrd, whose father had known the Wright family, Byrd spent an evening with Laura in—of all places—a Hollywood nightclub on the occasion of her 80th birthday. The two became friends. Sometime later, at Laura’s shabby apartment, Byrd encountered an astounding literary treasure.

“On one of my visits we happened to be talking about Mark Twain,” Byrd wrote to Gold. “She took me to her bed room, had me open her trunk, and got out several packages of letters from Sam Clemens. For several hours she read me portions of many of the letters. I think Lippincotts [the publishing company, J. B. Lippincott & Co.] offered her $20,000.00. I know that some of the letters were written during the [Civil] war.”

Laura Wright Dake told Byrd that her sisters and brother had urged her to sell the letters, but this was not her wish. “She made me promise, on my honor, that after her death I would destroy the letters and not let anyone read them. She said Sam Clemens wrote them to her and for her and that they were not to be published.” C. O. Byrd was one of those vanishing oddities of the 20th century, a man of his word. In his 1964 letter he blandly informed Gold, “I destryed [sic] the letters and followed all her instructions after her death.”

Laura died in 1932, around age 87, on the eve of the Franklin D. Roosevelt administration. Beyond her conversations with C. O. Byrd and her siblings, she never divulged information about her flirtation with Sam Clemens or her correspondence with Mark Twain.

Perhaps there was more to tell than rational scholarship could conceive, as Mark Twain would write at the conclusion of “My Platonic Sweetheart”: “In our dreams—I know it!—we do make the journeys we seem to make: we do see the things we seem to see; the people, the horses, the cats, the dogs, the birds, the whales, are real, not chimeras; they are living spirits, not shadows; and they are immortal and indestructible....We know this because there are no such things here, and they must be there, because there is no other place.”

Ron Powers is the author of Mark Twain: A Life, and Sam and Laura, a play about Twain and his lost love. Illustrator Jody Hewgill teaches at the Ontario College of Art and Design in Toronto.