Meet the Celebrity Skulls of Bolivia’s Fiesta de las Ñatitas

Each November, the Aymara people honor their special bond with the helpful spirits of the deceased

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e5/14/e5145c77-f74f-4654-8c5e-59e17ac17da9/n_24_of_48.jpg)

Before the gates opened to La Paz’s sprawling General Cemetery on November 8, an eager crowd had already begun to gather. By mid-morning, the living had filled the ground’s church and started to overflow into the labyrinth of paths between the graves. Many carried offerings of coca leaves, flower petals, cigarettes and candy.

Visitors also brought along some of their most cherished possessions, which happened to be the event’s raison d’être: human skulls.

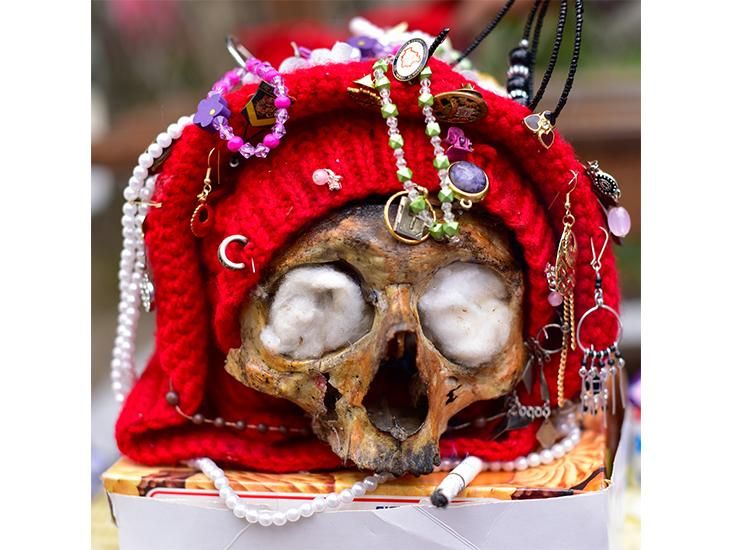

Called ñatitas—roughly translated as “little pug-nosed ones”—these skulls are thought to bestow blessings on those who care for them. The honored craniums are brought out from private shrines every year for the Fiesta de las Ñatitas. Usually held the week after All Saints and All Souls days, the event sees certain Bolivians gather in graveyards across the country to give gratitude to the ñatitas and celebrate the special bond forged between the skulls and their living beneficiaries.

“People are not coming to gawk,” says Paul Koudounaris, an art historian who documented the ñatitas in his book Memento Mori: The Dead Among Us and who has attended the fiesta since 2007. “They are either coming with their own skull or else coming to make offerings to someone else’s skull, so they feel blessed.”

Some outsiders liken this annual ritual to Mexico’s Day of the Dead, but that interpretation is flawed. The Fiesta de las Ñatitas is not held as a way to cope with the inevitability of death, nor to commemorate loved ones lost. Most of the skulls in participants’ possession are not even family members.

Some skulls are century-old heirlooms, while others are procured from archeological sites. Skulls may also come from local cemeteries, which do not sell plots in perpetuity, meaning there is always a high turnover of bones. Skulls that have their tops cut off are usually the products of medical schools.

All ñatitas are skulls, Koudounaris points out, but not all skulls are ñatitas. What differentiates the two is the relationship between the living owner and the skull—and a good relationship is never guaranteed.

“Everyone has a personality, and in some cases it might not be a good fit between a person and a skull,” Koudounaris says. “People will say, ‘I got this skull from my cousin who didn’t get along with it, but I’m getting along with it very well.’”

Bolivia’s special relationship between skulls and the living dates back centuries and originates with the Aymara people, an aboriginal group from the Altiplano region of the Andes. The Aymara regard death as a transition into another phase of existence, only divided by the thinnest of veils.

The ñatitas are vessels housing the souls of their former living residents, and they carry an association with fertility, luck and protection. Farmers used to bury skulls in their fields prior to planting, and accounts written as recently as 1918 describe sexual orgies that took place following rituals carried out with human craniums.

After the Spanish arrived in Bolivia in the 16th century, they began trying to eliminate such traditions, forcing native people to convert to Christianity and putting those caught attempting to perform magic with skulls on trial for witchcraft and necromancy. Rather than stamp out the Aymara’s relationship with skulls, however, beliefs surrounding them simply went underground.

It wasn’t until the 1970s, after indigenous farmers began moving into La Paz to seek work, that the practice began to resurface in a more public way. Since that time, the fiesta has been growing in scale, with 5,000 to 10,000 people participating in La Paz alone in recent years.

This year's event marked a record turnout at the General Cemetery, with estimates of up to 12,000 people coming and going throughout the day. The surge in numbers is likely due to a mix of logistics, including the fact that the fiesta fell on a Sunday, the only day of the week many Bolivians have off.

In addition, Aymaran culture is becoming much more accepted and celebrated. President Evo Morales is himself Aymaran and recently helped rename his country the Plurinational State of Bolivia in recognition of its multi-ethnicity. Equality for indigenous people is high on his agenda.

“There’s still a lot of racism here, primarily directed toward the Aymara,” Koudounaris says. “But there has been an incredible shift, in which people are no longer ashamed of their history and traditions and no longer have to hide it.”

The Roman Catholic Church still frowns upon the tradition, and in the past the La Paz chapel staunchly refused to allow the fiesta to take place on a Sunday. This year the priest did not perform a full Mass and noted in his sermon that “skulls must be buried” and “should not be venerated,” as Verónica Zapana reported for the local newspaper Página Sieta. But while the church does not exactly welcome the fiesta, it did hold three services for worshippers and their ñatitas this year that included readings from the Gospel.

After the benedictions, the skulls were slowly filed out of the church, carried in glass cases or protective boxes, or balanced atop velvet and satin pedestals. Onlookers sprinkled holy water on the shining domes of their craniums as they passed.

The ñatitas spent the rest of the day displayed throughout the cemetery, adorned in offerings. The skulls are often clad in sunglasses and hats, too: “You want your skull to look good, much as you’d want your child to look good at an important ceremony,” Koudounaris says.

After sunset, raucous parties called prestas break out in halls and salons nearby. One woman named Doña Ana, who keeps more than a dozen ñatitas, regularly attracts crowds of several hundred to her after-party.

“The invitations to the prestas for her skulls are outstanding—beautifully printed and embossed with the pictures of the skulls themselves—and I think her parties are the biggest,” Koudounaris says. “I remember a couple years ago all the skulls were given ham sandwiches. It was a bizarre touch.”

Outside of the fiesta, ñatitas tend to keep a low profile. Most are stored in shrines within private homes, where they grant blessings, protection and assistance to the people who venerate and make offerings to them, from preventing robberies to aiding in university studies.

Doña Susana Torrez, who brought her three ñatitas Fernando, José María and Isidro to the cemetery this year, told Zapana that the skulls regularly help her family. “I asked them to heal my husband, who had a stroke,” she said. “He was cured; now he’s healthy.”

On occasion, ñatitas can also be found aiding businesses. Two ñatitas known as Juanito and Juanita, for example, have been residents of the police headquarters of La Paz’s largest neighborhood for decades. Detectives there swear that the skulls help solve cases and coax confessions out of criminals.

Regardless of where they are housed, ñatitas are very much considered vibrant participants in the affairs of the living. Josue Gonzales, another festivalgoer, has had four ñatitas for more than a decade, inherited from his grandparents. As he told Zapana: “They are like my sisters.”

As the Aymara continue to become more visible in mainstream Bolivian society, such relationships will likely become all the more commonplace.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Rachel-Nuwer-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Rachel-Nuwer-240.jpg)