Memory Blocks

Artist Gunter Demnig builds a Holocaust memorial one stone at a time

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/stolpersteine631.jpg)

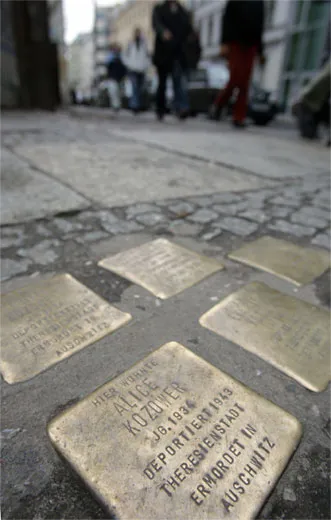

Visitors to the bustling center of Frankfurt am Main seldom venture as far north as Eschersheimer Landstrasse 405, where Holocaust victims Alfred Grünebaum and his elderly parents, Gerson and Rosa, once lived. But those who do will discover three four-by-four inch simple brass blocks known as stolpersteine—German for "stumbling stones"—embedded in the sidewalk in front of the doorway. Each simple memorial, created by Cologne artist Gunter Demnig, chronicles the person's life and death in its starkest details:

Here lived Alfred Grünebaum

Born 1899

Deported 1941

Kowno/Kaunas

Murdered 25 November 1941

[translated]

More than 12,000 such stones have been installed in roughly 270 German towns and cities since Demnig hammered the first brass blocks into Berlin's sidewalks in 1996. In contrast to Berlin's massive Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, Demnig's stolpersteine refocus the Holocaust on the individuals it destroyed.

"The monument in Berlin is abstract and centrally located," says Deming, who is 60. "But if the stone is in front of your house, you're confronted. People start talking. To think about six million victims is abstract, but to think about a murdered family is concrete."

The inspiration for stolpersteine dates back to the early 1990s, when Demnig traced the route taken by gypsies out of Cologne during Nazi deportation. He met a woman who didn't know that gypsies had once lived in her present neighborhood. The experience led the sculptor to consider the anonymity of concentration camp victims—a vast population identified by numbers instead of names. By creating a stone for each of them in front of their last homes, he says, "the name is given back."

Stolpersteine quickly gained notice. Germans either read about the stones or saw them at their feet, and many decided to commission them in their own communities. Individuals, neighborhood groups and even school classes now comb through German city archives to learn the names of people who once lived in their houses and streets. Then they contact Demnig.

He makes the brass stumbling blocks in his Cologne studio and eventually puts them in his red minivan and comes to town to install them. Each stolperstein gives an individual's name; year of birth and death (if known); and a brief line about what happened to the person. Sometimes the installation process involves only Demnig; other times, gatherers include local residents, relatives of the victims and religious or city officials. Demnig is on the go most of the year, and there's a waitlist for his services. In Hamburg, for instance, 600 stones have been commissioned but not yet crafted.

"It's very important not to lose the remembrance of this special part of German history," says Hamburg retiree Johann-Hinrich Möller, one of the volunteers who unearths life stories. "There are too many people who say 'we don't want to hear it anymore.' With the stolpersteine everybody sees that it happened in their neighborhood. They realize that there were people who lived in their house or even in their apartment."

Most stolpersteine are in front of the doorways of individual residences, but there are ten at the entrance to the Hamburg court house to commemorate Jewish judges who perished; 18 outside the headquarters of the Jewish Community, an organization that handles Jewish affairs; and 39 in front of two former Jewish orphanages. And while most stolpersteine commemorate Jews, some have been made for homosexual, political and religious victims.

"Stolpersteine are a metaphor for the Germans stumbling over this part of their past—something that won't go away—and that was the artist's point," says James E. Young of the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, author of two books on Holocaust memorialization. "Stolpersteine don't exist in places where you have to make your pilgrimage. You suddenly come upon them."

Roswitha Keller of Guenzburg, Germany, stumbled upon her Jewish past in 1999, following the death of her 90-year-old aunt. Keller found a document written by her grandfather August Stürzenacker recounting the circumstances under which his sisters-in-law, Gertrude Herrmann and Helene Mainzer were picked up by the Gestapo on October 20, 1940, and deported to the Vichy detention camp Gurs in southwestern France. "We were totally unaware of my father's Jewish background," Keller says. "He had never mentioned it to us." Having seen stolpersteine in Bonn, Keller commissioned two stones honoring her great-aunts which end with the word verschollen—missing.

The installation of the stumbling blocks is very much a German communal event. "These are memorials by and for the Germans," Young says. "These aren't really for the Jewish community but for Germans remembering."

Demnig sees stolpersteine and the ceremonies as a form of performance art. "People learn about people," he says, "and then you have discussions when others see the stone." Miriam Davis, granddaughter of Alfred Grünebaum, traveled to Frankfurt am Main from Silver Spring, Maryland, in October 2004. The family had received an invitation to attend the stone's installation from Gisela Makatsch of Steine Gegen Das Vergessen (Stones Against Being Forgotten), a group that helps Demnig place stolpersteine, who had researched the Davis history. Davis and Makatsch clicked and have stayed close since. "How could I ask for a richer way to comprehend the changes that have happened in Germany?" Davis says.

Not everyone approves of the stolpersteine. Charlotte Knobloch, president of the Central Council of Jews in Germany, has objected to people walking on the names of the dead. Some homeowners worry that the value of their property might decrease. In some towns in eastern Germany, stolpersteine have been ripped out of the pavement.

Yet more and more stolpersteine are appearing, even beyond Germany's borders. Demnig has installed them in sidewalks in Austria and Hungary. Later this year he's heading for the Netherlands, and next year he's off to Italy.

"I will be making stolpersteine until I die," Demnig says. "So many people in Germany are involved and now in the whole of Europe. I have to continue. This is not a project for the past but for the future."

Lois Gilman is a freelance writer whose grandparents lived in Frankfurt am Main and escaped the Nazis in 1939.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/eric-jaffe-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/eric-jaffe-240.jpg)