Mister Rogers Pioneered Speaking to Kids About Gun Violence

We need the children’s television icon now more than ever

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/2e/5c/2e5cd3b6-ddac-4ae5-ba55-9593c44bbb7f/opener-jun2018_g01_toc-wr.jpg)

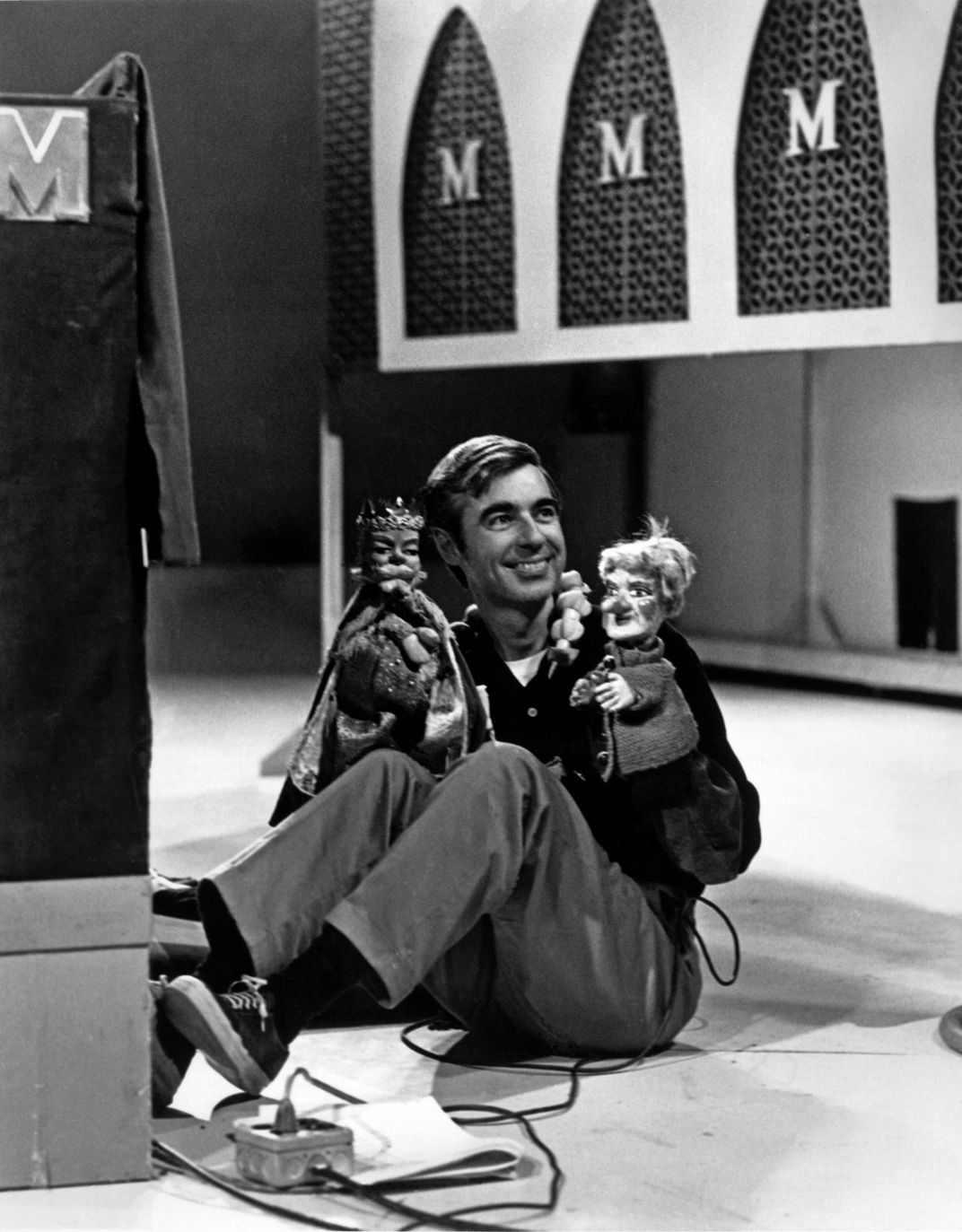

"Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood” had been on the air nationwide for only four months when Robert Kennedy was shot in Los Angeles on June 5, 1968. But the show’s creator, Fred McFeely Rogers, knew that children would need help processing the assassination—the second in the United States in just two months—so he worked through the night of June 6 on a special episode for parents. The half-hour show was taped the following day and aired on public television that evening, the day before Kennedy’s funeral. Fifty years later, it’s still mesmerizing TV.

The black-and-white scene opens on the perennially fearful Daniel Striped Tiger, a hand puppet worried about how breathing works. Daniel watches as his (human) friend Lady Aberlin shows that after she has let the air out of a balloon, she can blow it up again. As Lady Aberlin begins to reinflate the balloon, Daniel abruptly asks, “What does assassination mean?”

Lady Aberlin puts the balloon down. “Have you heard that word a lot today?”

“Yes, and I didn’t know what it meant.”

Lady Aberlin falters. “Well,” she says, “it means somebody getting killed in a—a sort of surprise way.”

“That’s what happened, you know!” says Daniel excitedly. “That man killed that other man!” Slowly he adds, “Too many people are talking about it.”

When the show cuts to Mister Rogers—so young!—on an empty set, he’s clearly troubled. Twisting his fingers, he says, “I plead for your protection and support of your young children. There is just so much that a very young child can take.

In that moment Mr. Rogers became Mister Rogers. “This new children’s TV figure was suddenly talking to the whole family,” says Maxwell King, author of the upcoming Rogers biography The Good Neighbor and former executive director of the Fred Rogers Center for Early Learning and Children’s Media. The center, at Saint Vincent College in Latrobe, Pennsylvania (Rogers’ hometown), houses Rogers’ archive and hosts the Fred Forward Conference on childhood development research. “Rogers wasn’t just a soft-spoken newbie giving puppet shows for kids,” says King. “He was a very serious thinker about the impact of media on children.”

It was a topic Rogers had contemplated since he saw an episode of the “Three Stooges” as a college senior in 1951. He’d already been accepted at divinity school but straightaway got a job at NBC. His goal: to learn enough about the medium to produce children’s television shows where men weren’t mashing pies into each other’s faces. He worked his way up from assistant-producing to floor-managing before he was asked to develop programming for a new educational TV station in Pittsburgh. One show he created—“The Children’s Corner”—won an award in 1955 as the best locally produced kids’ show in the nation.

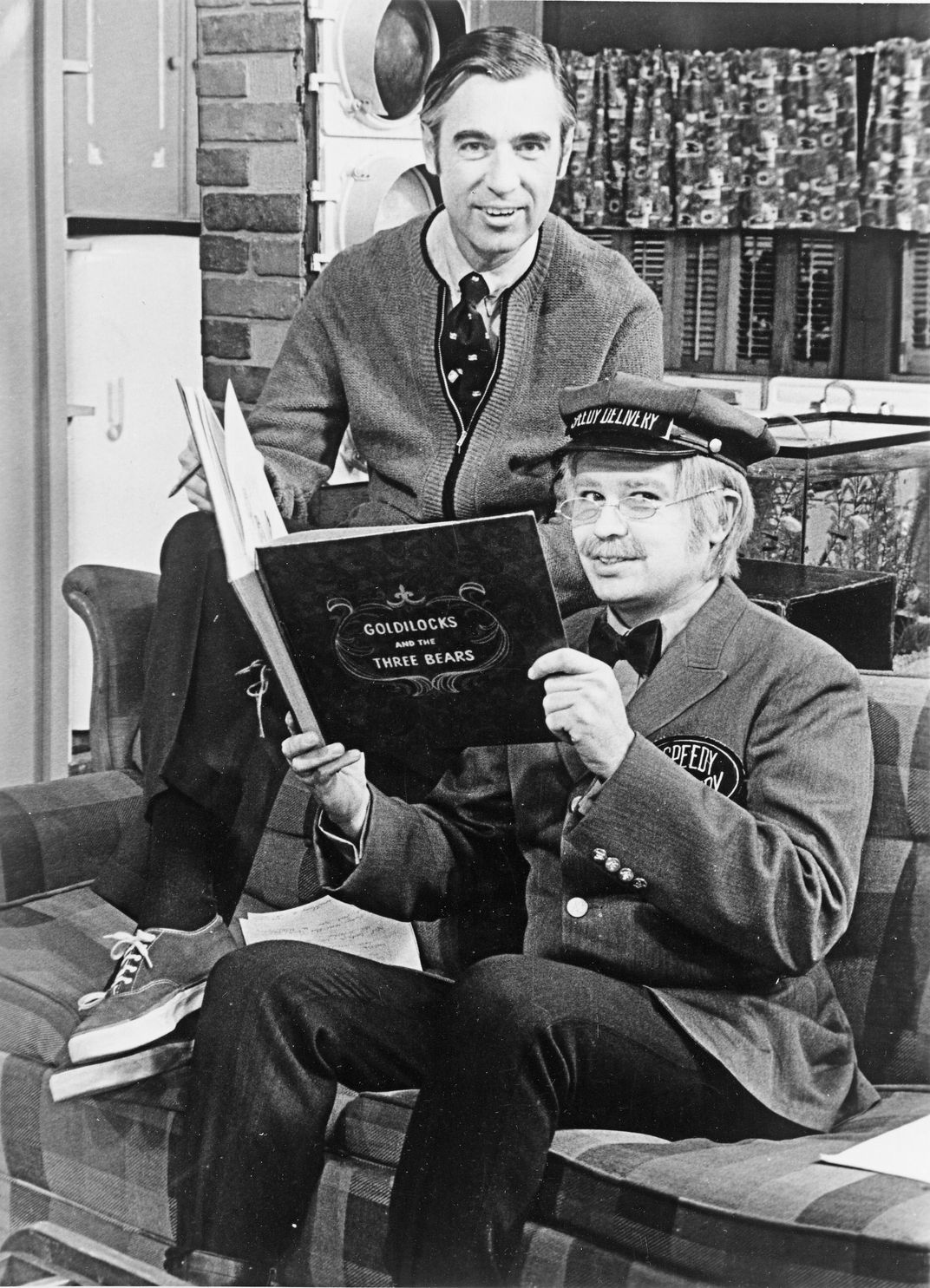

In his spare time, Rogers earned graduate degrees in theology and child development; he was ordained as a Presbyterian minister in 1963 and given the singular assignment of continuing his ministry via mass media. He did, moving to Toronto to host his own children’s show, “Misterogers,” for the Canadian Broadcasting Company. A few years later, he acquired the rights to the program, moved back to Pittsburgh, and retooled the show for public television. “Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood” was an antidote to slapstick comedies and lackluster children’s shows.

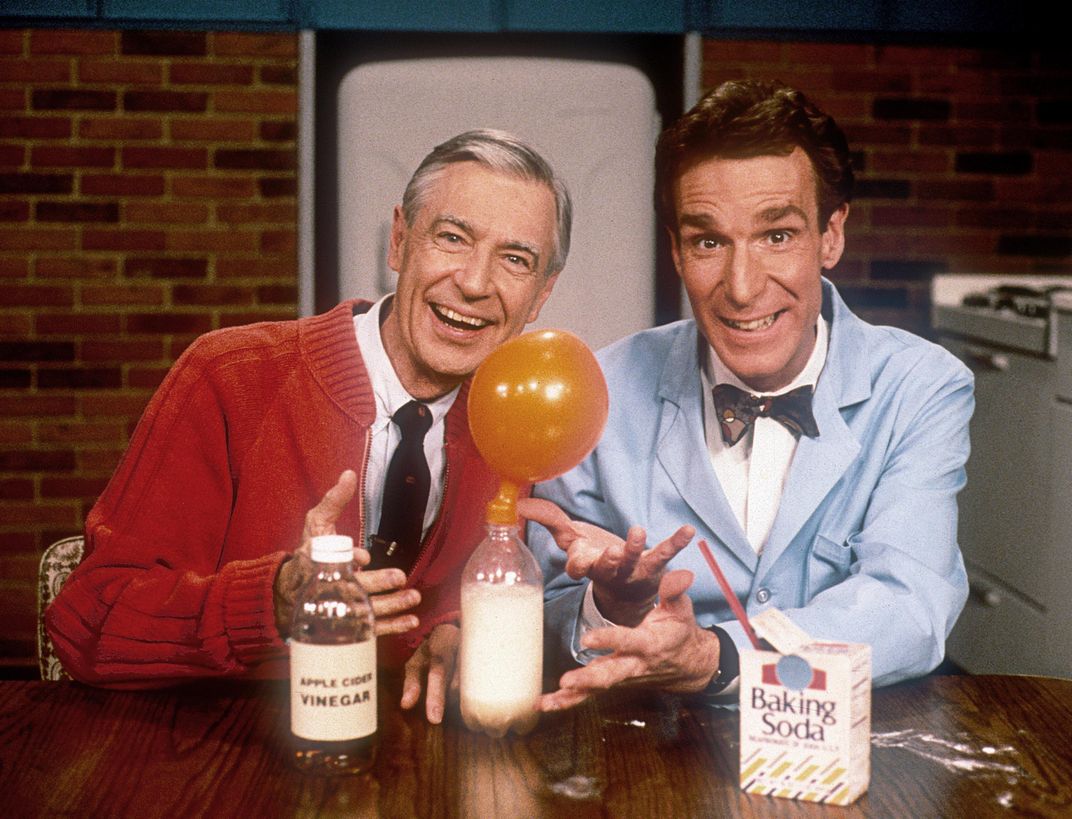

The after-school TV landscape in 1968 was pockmarked with local shows hosted by perky adults dressed as Skipper Sam, Cactus Cal and other “fun” characters who mostly introduced cartoons and clowned around with their studio audiences. Rogers’ program, airing at lunchtime or after school, didn’t cut capers. His set looked like a pediatrician’s office. He came in wearing Dad at Work clothes and changed into Dad at Home clothes, replacing his jacket with a cardigan (made by his mom) and his shoes with (embarrassing) navy Keds. He looked steadily into the camera, making it seem as if he saw each child individually. He spoke slowly and quietly, used battered old puppets instead of glitzy made-for-TV ones, and talked about feelings. And at the end of every half-hour show for more than 30 years, he promised each viewer, “You’ve made this day a special day, by just your being you.”

The World According to Mister Rogers: Important Things to Remember

A timeless collection of wisdom on love, friendship, respect, individuality, and honesty from the man who has been a friend to generations of Americans.

Adults watching him had to wonder if Fred Rogers ever stopped being Mister Rogers. If one of his two sons were to scream “I hate you!” would his reply be as quaintly measured as it was on the show? Probably. (“It was a little tough having the second Christ as my dad,” one of the boys later admitted.) “What you see is what you get with Fred,” his wife, Joanne, once told CNN, adding that she’d never been able to emulate her husband’s patience. His tranquillity could seem frightening or dorky, but it was sincere, and it was part of why we trusted him. There was nothing we could do that would shock Mister Rogers or make him angry at us.

The terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, took place after Rogers had finished filming his final shows, but he taped a public service announcement for parents and caregivers—“those of you who grew up with us”—asking them to protect a new generation of children. “I’m so grateful to you for helping the children in your life to know that you’ll do everything you can to keep them safe and to help them express their feelings in ways that will bring healing in many different neighborhoods.”

Fred Rogers died in 2003, at age 74, but we still reach for his words. After the mass shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in February, after the Florida International University bridge collapse, after the Austin bombings, after each tragedy, Mister Rogers reappears as a social media meme. In countless Twitter and Facebook posts, a sentiment Rogers first voiced to make John Lennon’s death in 1980 less scary is superimposed over an image of the man with a saintly smile and a cardigan: “When I was a boy and I would see scary things in the news, my mother would say to me, ‘Look for the helpers. You will always find people who are helping.’”

Fred Rogers was one of those helpers and he believed that each of us could be, too. He liked us just the way we are, but he also gave us a way to be better.

The ABCs of Tragedy

For three decades TV shows for kids have been responding to natural as well as manmade disasters.

Challenger Explosion | 3-2-1 Contact | Feb. 9, 1986

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c5/6e/c56ed23f-d756-475f-9cd0-2f9b6946730f/jun2018_b12_prologue.jpg)

An episode about the lives of astronauts was repackaged to explain a tragedy witnessed by children who had tuned in to see Christa McAuliffe become the first teacher in space.

Exxon Valdez Oil Spill | Captain Planet and the Planeteers | Sept. 15, 1990

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/07/98/0798a257-2f10-4b1b-862a-1186736c20ad/jun2018_b14_prologue.jpg)

The premiere of this cartoon, which aired on TBS during the cleanup of the 1989 spill, gave its young heroes the power to protect the earth from careless oil drilling.

L.A. Riots | Nick News with Linda Ellerbee | May 6, 1992

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/84/89/8489015e-1917-4dcf-b4f2-585af179ebe9/jun2018_b08_prologue.jpg)

This kid-focused newsmagazine explored many events in its 25 years. Among the first: a conversation with Los Angeles children two days after the deadly riots.

9/11 | Zoom | Sept. 21, 2001

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/0b/43/0b430f00-86a8-46a8-9661-7914aee6a155/jun2018_b15_prologue.jpg)

“Zoom” received a flood of emails from scared viewers after the terrorist attacks. This special was about how kids could help their communities in the aftermath.

First Anniversary of 9/11 | Reading Rainbow | Sept. 3-6, 2002

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/35/0f/350f1c0a-fbc8-40f9-b69f-5856181e38f7/jun2018_b03_prologue.jpg)

“A hero is someone who helps another human being,” a New York City firefighter told host LeVar Burton in a series of episodes about hope, heroism and inclusion.

Hurricane Sandy | Sesame Street | Nov. 9, 2012

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a9/4c/a94c6ba9-1259-4f28-8b96-11c81b4162a2/jun2018_b09_prologue.jpg)

Sesame Workshop condensed a week of shows that first aired in 2001 into a single episode in which Big Bird’s nest was destroyed by a storm.

Parkland Shooting | Nickelodeon | March 14, 2018

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f8/97/f8975485-0aa7-463b-9a7a-2fc7c8683a21/jun2018_b07_prologue.jpg)

For 17 minutes on National Walkout Day to protest gun violence, Nickelodeon suspended programming “in support of kids leading the way today.”

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.