Mixing Movies and Politics

From Mrs. Miniver to Avatar, how big studio films have influenced public opinion

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20111024092018Miniver_blog_thumb1.jpg)

In “The Sniping of Partisans, This Time on Screen,” New York Times entertainment reporter Michael Cieply pointed out the political implications of releasing a film like Lincoln, Steven Spielberg’s biopic of the assassinated President, before or after the 2012 Presidential election.

Cieply went on to cite several films, including the upcoming Butter from the Weinstein Company, that he felt might “play a role in voters’ choice for the White House.” Cieply’s opinion, buttressed by quotes from the likes of Harvey Weinstein, is that we have reached the point where movies and politics have converged. Actually, that point arrived a long time ago.

Examples of advocacy filmmaking stretch back to the beginnings of cinema. I am simultaneously appalled and charmed by films made about the Spanish-American war, in particular Battle of Manila Bay (1898), a short that helped make the reputations of J. Stuart Blackton and his partner Albert E. Smith. Working with boat models in a bathtub, Blackton reenacted Admiral George Dewey’s naval victory for the camera. When his footage reached vaudeville houses a couple of weeks later, it was a tremendous hit, causing a succession of imitators to try their hands at faking war footage. Edward Atmet used miniatures to make Bombardment of Matanzas, Firing Broadside at Cabanas and other films. Film historian Charles Musser believes that The Edison Company shot fake battle movies like Cuban Ambush in New Jersey. To cash in on the war craze, the Biograph company simply retitled its film Battleships “Iowa” and “Massachusetts” to Battleships “Maine” and “Iowa.” Musser cites one newspaper article that reported “fifteen minutes of terrific shouting” at its showing.

World War I unleashed a tidal wave of anti-German propaganda from US filmmakers. Perhaps no one capitalized on the mood of the country better than Erich von Stroheim, who played villainous Huns so effectively that he became “The Man You Love to Hate.” Liberty Bond rallies featuring stars like Charlie Chaplin, Mary Pickford, and Douglas Fairbanks drew hundreds of thousands of spectators; Chaplin even made a short, The Bond, to help sales. It was one of at least thirty bond fundraising films released by the industry.

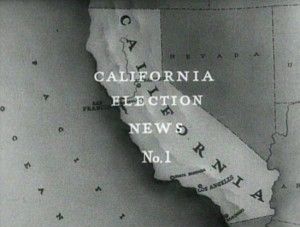

Some of the industry’s dirtiest political tricks took place in California in 1934. As detailed in Greg Mitchell’s book The Campaign of the Century: Upton Sinclair’s Race for Governor (Random House), media moguls like William Randolph Hearst and the Chandler family (of The Los Angeles Times) made a concerted effort to defeat Sinclair, whose End Poverty in California (EPIC) program was gathering significant grass-roots support. Joining in the attack: MGM, which under the direction of studio head Louis B. Mayer and producer Irving Thalberg filmed two newsreels that presented Sinclair in the worst possible light. Actors playing toothless immigrants swore their devotion to the candidate, while “hoboes” gathered at the California border, waiting for Sinclair’s election so they could take advantage of his socialist policies.

Newsreels have long since been supplanted by television news, but filmmakers never stopped making advocacy pieces. When director Frank Capra saw Leni Riefenstahl’s notorious pro-Nazi documentary Triumph of the Will, he wrote, “Satan himself couldn’t have devised a more blood-chilling super-spectacle.” Capra responded with Why We Fight, a seven-part, Oscar-winning documentary that put the government’s objectives into terms moviegoers could understand.

When William Wyler set out to direct Mrs. Miniver for MGM, he admitted, “I was a warmonger. I was concerned about Americans being isolationist.” The story of how an upper-class British family reacts to German attacks, the film made joining the war effort seem like common decency. Mrs. Miniver not only won six Oscars, it became a prime propaganda tool. President Franklin D. Roosevelt asked that the movie’s closing sermon be broadcast over the Voice of America and distributed as leaflets throughout Europe. Winston Churchill was quoted as saying that the film’s impact on “public sentiment in the USA was worth a whole regiment.” Wyler received a telegram from Lord Halifax saying that Mrs. Miniver “cannot fail to move all that see it. I hope that this picture will bring home to the American public that the average Englishman is a good partner to have in time of trouble.” (Years later, Wyler admitted that his movie “only scratched the surface of the war. I don’t mean it was wrong. It was incomplete.”)

Some may find the idea that movies can directly influence political discourse hard to swallow. Sure, movies like Outfoxed or The Undefeated make strong arguments. But aren’t they just preaching to their followers? Can they really change the minds of their opponents?

To some extent all films are political, because all films have a point of view. Movies that deal with perceived injustices—in Spielberg’s case, The Sugarland Express and Amistad—are on some level criticizing a system that allows them to occur. Even Spielberg’s mass-oriented adventures, like the Indiana Jones series, express a points-of-view: Jones, on the surface apolitical, is drawn into battling tyrannical regimes that threaten the American way of life.

On the other hand, setting out with the goal of making political points through film almost never succeeds, as the graveyard of recent Iraq war-related movies shows. A film has to capture the zeitgeist, it has to deliver a message that moviegoers are ready to accept, in order to have an impact of the culture. When it works, as in the phenomenal box-office results for titles as disparate as Iron Man and Avatar, it doesn’t even matter whether the films have artistic merit.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/daniel-eagan-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/daniel-eagan-240.jpg)