When I was a small child in the late 1950s, my family lived on a reindeer farm in the fjords of Greenland. My father, Jens Rosing, had deep roots in the country. Some of his ancestors were Inuits who’d come over from Canadian islands 800 years earlier. Others were Danes who’d arrived in the early 1800s, just after the Napoleonic Wars. In addition to breeding reindeer, my father was painting, drawing and writing books. He also made small pictures of seals, sled dogs, polar bears and other iconic Greenland scenes.

There was plenty of wilderness around our home, but there was no school. So we moved to Denmark, where my mother’s family lived. But we always felt drawn to Greenland. When I was a teenager, my father became the director of the Greenland National Museum and Archives, in Nuuk. Soon after that, I moved to a small settlement just north of the Arctic Circle where I worked as a substitute teacher and line-fished halibut from a dog sled.

I became a geologist mainly because I loved spending time outdoors in Greenland. There’s no place on earth I find more tranquil. When I took a group of students there recently to do fieldwork, one of them remarked, “It’s a long day when you’re alone with yourself.” In Greenland, you can really experience what that’s like. Even though the climate is harsh, you can live independently, as long as you don’t do anything stupid. When you live in a city, your survival depends on everyone else around you not being stupid.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/1a/99/1a99f6a3-94a6-4ef2-9424-db300d10f421/may2019_a09_ultimathulegreenland.jpg)

It’s a mistake, though, to think of Greenland as isolated. There’s a stereotype of Inuit people who live out in the middle of nowhere and go outside to knock some animal on the head and eat it raw. In reality, Greenland has a literacy rate of 100 percent, and its people have plenty of knowledge and opinions about the rest of the world. The major classic novels were translated into Greenlandic and read widely starting in the mid-1800s. Robinson Crusoe ran as a serial in the newspaper. These days, even the most remote houses are usually connected to the internet.

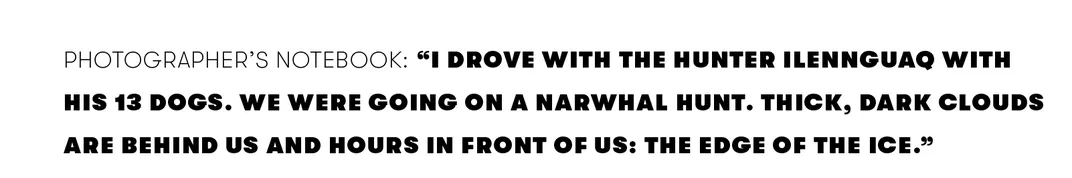

My grandfather Otto Rosing captured the contradiction between remoteness and worldliness back in 1943, when he was a pastor assigned to the Lutheran church in Thule. In a letter around that time, he described an afternoon outing with his family on a small motorboat when a flotilla of ships from Washington, D.C. suddenly appeared, ready to set up a large new weather and radio station. Although my grandfather was just a local pastor, he told the Americans they weren’t authorized to make landfall from the United States without government approval. “Greenland is the land of surprises these days,” he wrote. “You can live in prehistoric times one day and get entangled in international affairs the next.”

That radio station expanded into the Thule Air Base, the northernmost U.S. military base in the world, and it drew thousands of Americans over the years. They brought a lot of new things to Greenland: Coca-Cola, blue jeans, rock ’n’ roll music. You’ll hear people lamenting this, saying that the Western world is destroying the Inuit way of life. I find it interesting, though, that when Elvis’ music came to Denmark, people didn’t think of it as a cultural disaster. Humans everywhere are curious about new gadgets and goods. They’re always looking for new inspiration.

There are parts of the world where colonizers forced the local people to change their ways of life. For the most part, Greenlanders have had a lot of freedom to make their own choices, and they’ve chosen to keep the parts of their own culture that work best for them.

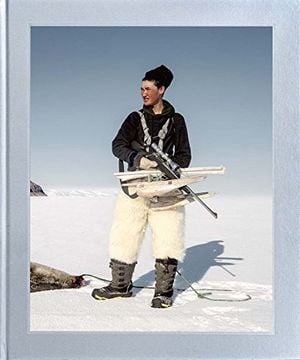

Take the man in the opening spread of this story. He’s wearing modern boots because they’re much more rugged than traditional Inuit footwear. But he’s also wearing polar bear skin pants. That’s not a fashion statement. He prefers warm, water-repellent polar bear skin to synthetic alternatives. Choosing the traditional option over the modern one was a practical decision for him.

We like to romanticize people who live in the wilderness. But when I lived in Concord, Massachusetts, people liked to tell me there was a footpath between Walden Pond and Concord because Henry David Thoreau often went into town to have tea with friends. He didn’t want to sit alone in his cabin all the time. He wanted to interact with other people, to hear new stories and expand his world. Why should we assume the Inuit people of Greenland are any different?

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

:focal(3012x983:3013x984)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6b/31/6b310b0f-0ddc-487e-8a54-2ebf3b847c4d/may2019_a05_ultimathulegreenland.jpg)