Monopoly Was Designed to Teach the 99% About Income Inequality

The story you’ve heard about the creation of the famous board game is far from true

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/92/4c/924c01b6-f45b-4af8-bddd-aafa3fe47970/dec15_c02_phenom.jpg)

In the 1930s, at the height of the Great Depression, a down-on-his-luck family man named Charles Darrow invented a game to entertain his friends and loved ones, using an oilcloth as a playing surface. He called the game Monopoly, and when he sold it to Parker Brothers he became fantastically rich—an inspiring Horatio Alger tale of homegrown innovation if ever there was one.

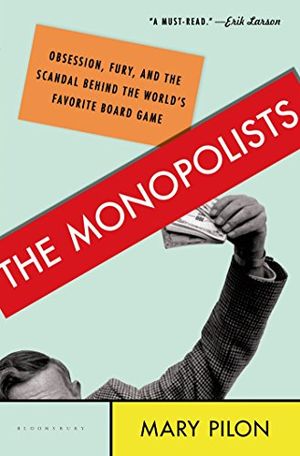

Or is it? I spent five years researching the game’s history for my new book, The Monopolists: Obsession, Fury, and the Scandal Behind the World’s Favorite Board Game, and found that Monopoly’s story began decades earlier, with an all-but-forgotten woman named Lizzie Magie, an artist, writer, feminist and inventor.

Magie worked as a stenographer and typist at the Dead Letter Office in Washington, D.C., a repository for the nation’s lost mail. But she also appeared in plays, and wrote poetry and short stories. In 1893, she patented a gadget that fed different-sized papers through a typewriter and allowed more type on a single page. And in 1904, Magie received a patent for an invention she called the Landlord’s Game, a square board with nine rectangular spaces on each side, set between corners labeled “Go to Jail” and “Public Park.” Players circled the board buying up railroads, collecting money and paying rent. She made up two sets of rules, “monopolist” and “anti-monopolist,” but her stated goal was to demonstrate the evils of accruing vast sums of wealth at the expense of others. A firebrand against the railroad, steel and oil monopolists of her time, she told a reporter in 1906, “In a short time, I hope a very short time, men and women will discover that they are poor because Carnegie and Rockefeller, maybe, have more than they know what to do with.”

The Landlord’s Game was sold for a while by a New York-based publisher, but it spread freely in passed-along homemade versions: among intellectuals along the Eastern Seaboard, fraternity brothers at Williams College, Quakers living in Atlantic City, writers and radicals like Upton Sinclair.

It was a Quaker iteration that Darrow copied and sold to Parker Brothers in 1935, along with his tall tale of inspired creation, a new design by his friend F.O. Alexander, a political cartoonist, and what is surely one of U.S. history’s most-repeated spelling errors: “Marvin Gardens,” which a friend of Darrow’s had mistranscribed from “Marven Gardens,” a neighborhood in the Atlantic City area.

Magie, by then married to a Virginia businessman (but still apparently a committed anti-monopolist), sold her patent to Parker Brothers for $500 the same year, initially thrilled that her tool for teaching about economic inequality would finally reach the masses.

Well, she was half right.

Monopoly became a hit, selling 278,000 copies in its first year and more than 1,750,000 the next. But the game lost its connection to Magie and her critique of American greed, and instead came to mean pretty much the opposite of what she’d hoped. It has taught generations to cheer when someone goes into bankruptcy. It has become a staple of pop culture, appearing in everything from One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest and “Gossip Girl” to “The Sopranos.” You can play it on your iPhone, win prizes by peeling game stickers off your McDonald’s French fries, or collect untold “Banana Bucks” in a movie tie-in version commemorating Universal’s Despicable Me 2.

As for Magie, I discovered a curious trace of her while searching through newly digitized federal records. In the 1940 census, taken eight years before she died, she listed her occupation as a “maker of games.” In the column for her income she wrote, “0.”

Editor's Note: The article has been updated to reflect the fact that Despicable Me 2 is not a Disney movie.

Related Reads

The Monopolists: Obsession, Fury, and the Scandal Behind the World's Favorite Board Game