Motown Turns 50

For years, the recording industry excluded black artists. Along came Motown, and suddenly everyone was singing its tunes

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/The-Temptations-Motown-631.jpg)

Editor’s note: It’s been 50 years since Berry Gordy founded Motown, a record company that launched scores of careers, created a signature sound in popular music and even helped bridge the racial divide. This article first appeared in the October 1994 issue of Smithsonian; it has been edited and updated in honor of the anniversary.

It was nearly 3 A.M. but Berry Gordy couldn’t sleep. That recording kept echoing in his head, and every time he heard it he winced. The tempo dragged, the vocals weren’t perky enough, it just didn’t have the edge. Finally, he got out of bed and went downstairs to the homemade studio of his struggling record company. He grabbed the phone and rang his protégé Smokey Robinson, who had written the lyrics and sang lead with a little-known group called the Miracles: “Look, man, we’ve got to do this song again . . . now . . . tonight!” Robinson protested, reminding Gordy that the record had been distributed to stores and was being played on the radio. Gordy persisted, and soon he had rounded up the singers and the band, all except the pianist. Determined to go ahead with the session, he played the piano himself.

Under Gordy’s direction, the musicians picked up the tempo, and Robinson pepped up his delivery of the lyrics, which recounted a mother’s advice to her son on finding a loving bride: “Try to get yourself a bargain son, don’t be sold on the very first one . . . . ” The improved version of “Shop Around” was what Gordy wanted—bouncy and irresistibly danceable. Released in December 1960, it soared to No. 2 on Billboard’s pop chart and sold more than a million copies to become the company’s first gold record. “Shop Around” was the opening salvo in a barrage of smash hits in the 1960s that turned Gordy’s humble studio into a multimillion-dollar corporation and added a dynamic new word to the lexicon of American music: “Motown.”

Gordy, a Detroit native, started the company in 1959, deriving its name from the familiar moniker “Motor City.” Motown combined elements of blues, gospel, swing, and pop with a thumping backbeat for a new dance music that was instantly recognizable. Competing for teen attention primarily against records by the Beatles, who were at the height of their popularity, Motown radically altered the public’s perception of black music, which for years had been kept out of the mainstream.

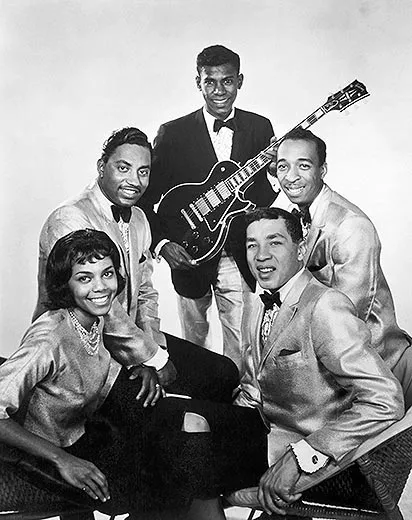

White youths as well as black were captivated by the rhythmic new sound, though the musicians who produced it were black and many of the performers were teenagers from Detroit’s housing projects and rundown neighborhoods. Prodding and grooming those raw talents, Gordy transformed them into a roster of dazzling artists who stunned the pop music world. The Supremes, Mary Wells, the Temptations, the Miracles, the Contours, Stevie Wonder, the Marvelettes, Diana Ross, Marvin Gaye, Martha and the Vandellas, the Four Tops, Gladys Knight and the Pips, Michael Jackson—those were just some of the performers who had people singing and dancing all over the world.

In 1963, when I was in junior high school and completely infatuated with Motown music, I persuaded my dad to drive me past Hitsville U.S.A., which is what Gordy called the little house where he did his recording. We had just moved to Detroit from the East Coast, and the possibility of seeing some of the music makers was the only thing that soothed the pain of relocation. I was disappointed to find not one star lolling about the yard, as was rumored to happen, but a few months later my dream came true at the Motown Christmas show in downtown Detroit. A girlfriend and I queued up at the Fox Theater for an hour one chilly morning and paid $2.50 to see the revue. We rocked our shoulders, snapped our fingers, danced in our seats and sang along as act after act lit up the stage. I grew hoarse from screaming for the fancy footwork of the Temptations and the romantic crooning of Smokey Robinson. Today I still burst into song whenever I hear a Motown tune.

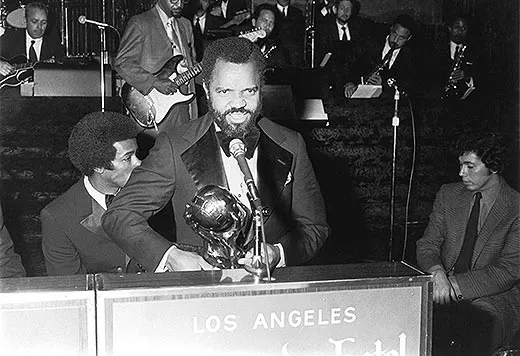

No longer star-struck but still awed by the company’s unparalleled success, I recently visited Gordy at his hilltop mansion in Bel-Air, an opulent enclave of Los Angles. We settled into a stately sitting room furnished with a plump damask sofa and large armchairs. An array of black-and-white photographs of family, Motown celebrities and other stars adorned the walls. Gordy was dressed casually in an olive-green sweatsuit. His 1950s processed pompadour has given way to a graying, thinning close-cut, but he remains exuberant and passionate about his music.

Twice during our conversation he steered me to the photographs, once to point out a youthful Berry with singer Billie Holiday at a Detroit nightclub, and again to show himself with Doris Day. Brash and irrepressible, he had sent Day a copy of the very first song he had written, almost 50 years ago, certain she would record it. She did not, but Gordy still remembers the lyrics, and, without any prodding from me, rendered the ballad in his trilling tenor voice. His bearded face erupted into an impish grin as he finished. “With me you might get anything,” he chuckled. “You never know.”

He talked about his life and the music and the people of Motown, his reminiscences burbling forth—stories animated with humor, snatches of songs and imitations of instruments. He told how he shirked piano practice as a child, preferring instead to compose boogie-woogie riffs by ear, and consequently never learned to read music. He recalled how 18-year-old Mary Wells badgered him at a nightclub one evening about a song she had written. After hearing her husky voice, Gordy persuaded her to record it herself, launching Wells on a course that made her Motown’s first female star.

A music lover since his tender years, Gordy didn’t set out to build a record company. He dropped out of high school when he was a junior and spent a decade finding his niche. Born in 1929, the seventh of eight children, he inherited an entrepreneurial instinct from his father. Gordy senior ran a plastering and carpentry business and owned the Booker T. Washington Grocery Store. The family lived above the store, and as soon as the kids could see over the counter, they went to work serving customers. Young Berry hawked watermelons from his father’s truck in the summer and shined shoes on downtown streets after school. On Christmas Eve, he and his brothers would huddle around an oil-can fire selling trees until late in the evening.

After quitting school, Gordy stepped into the boxing ring, hoping to pummel his way to fame and fortune like Detroit’s Joe Louis, every black boy’s hero in the 1940s. Short and scrappy, Gordy put in a tenacious but ultimately unrewarding few years before being drafted. When he returned from the Army, where he earned his high school equivalency diploma, he opened a record store specializing in jazz. Set on attracting an urbane audience, he eschewed the earthy, foot-stomping music of singers like John Lee Hooker and Fats Domino. Ironically, it was just what his customers wanted, but Gordy was slow to catch on, and his store failed.

He found work on the Ford Motor Company assembly line, earning about $85 a week attaching chrome strips to Lincolns and Mercurys. To relieve the tedium of the job, he made up songs and melodies as the cars rolled by. In the late ’50s Gordy frequented Detroit’s black nightclubs, establishing his presence, peddling his songs and mentoring other songwriters. His big break came when he met Jackie Wilson, a flamboyant singer with matinee-idol looks who had just launched a solo career. Gordy wrote several hit songs for Wilson, including “Reet Petite,” “Lonely Teardrops” and “That is Why.” It was during this time that he also met William (Smokey) Robinson, a handsome, green-eyed teenager with a mellow falsetto voice and a notebook full of songs.

Gordy helped Robinson’s group, the Miracles, and other local wannabes find gigs and studios to cut records, which they sold or leased to big companies for distribution. There wasn’t much money in it, however, because the industry regularly exploited struggling musicians and songwriters. It was Robinson who persuaded Gordy to set up his own company.

Such a venture was a major step. Ever since the dawn of the recording industry at the turn of the century, small companies, and especially black-owned companies, had found it almost impossible to compete in a business dominated by a few giants who could afford better promotion and distribution. Another frustration was the industry’s policy of designating everything recorded by blacks as “race” music and marketing it only to black communities.

By the mid-50s the phrase “rhythm and blues” was being used to refer to black music, and “covers” of R&B music began flooding the mainstream. Essentially a remake of an original recording, the cover version was sung, in this instance, by a white performer. Marketed to a large white audience as popular, or “pop,” music, the cover often outsold the original, which had been distributed only to blacks. Elvis Presley rose to prominence on such covers as “Hound Dog” and “Shake, Rattle and Roll;” Pat Boone “covered” several R&B artists, including Fats Domino. Covers and skewed marketing for R&B music posed formidable challenges for black recording artists. To make big money, Gordy’s records would have to attract white buyers; he had to break out of the R&B market and cross over to the more lucrative pop charts.

Gordy founded Motown with $800 that he borrowed from his family’s savings club. He bought a two-story house on West Grand Boulevard, then an integrated street of middle-class residences and a sprinkling of small businesses. He lived upstairs and worked downstairs, moving in some used recording equipment and giving the house a new coat of white paint. Remembering his days on the assembly line, he envisioned a “hit factory.” “I wanted an artist to go in one door as an unknown and come out another a star,” he told me. He christened the house “Hitsville U.S.A,” spelled out in large blue letters across the front.

Gordy didn’t start out with a magic formula for hit records, but early on a distinct sound did evolve. Influenced by many types of African-American music—jazz, gospel, blues, R&B, doo-wop harmonies—Motown musicians cultivated a pounding backbeat, an infectious rhythm that kept teenagers gyrating on the dance floor. To pianist Joe Hunter, the music had “a beat you could feel and could hum in the shower. You couldn’t hum Charlie Parker, but you could hum Berry Gordy.”

Hunter was one of many Detroit jazzmen Gordy lured to Motown. Typically, the untrained Gordy would play a few chords on the piano to give the musicians a hint of what was in his head; then they would flesh it out. Eventually, a group of those jazz players became Motown’s in-house band, the Funk Brothers. It was their innovative fingerwork on bass, piano, drums and saxophone, backed up by handclaps and the steady jangling of tambourines that became the core of the “Motown Sound.”

Adding words to the mix fell to the company’s stable of producers and writers, who were adroit at penning squeaky-clean lyrics about young love—yearning for it, celebrating it, losing it, getting it back. Smokey Robinson and the team of Lamont Dozier and brothers Eddie and Brian Holland, known as HDH, were especially prolific, churning out hit after hit chock-full of rhyme and hyperbole. The Temptations sang about “sunshine on a cloudy day” and a girl’s “smile so bright” she “could’ve been a candle.” The Supremes would watch a lover “walk down the street, knowing another love you’d meet.”

Spontaneity and creative wackiness were standard at Motown. The Hitsville house, open round the clock, became a hangout. If one group needed more backup voices or more tambourines during a recording session, someone was always available. Before the Supremes ever scored a hit, they were often summoned to provide the insistent handclapping heard on many Motown records. No gimmick was off limits. The loud thumping at the beginning of the Supremes’ “Where Did Our Love Go” is literally the footwork of Motown extras stomping on wooden planks. The tinkling lead notes on one Temptations record came from a toy piano. Little bells, heavy chains, maracas and just about anything that would shake or rattle were employed to boost the rhythm.

An echo chamber was rigged up in an upstairs room, but occasionally the microphone picked up an unintended sound effect: noisy plumbing from the adjacent bathroom. In her memoirs, Diana Ross recalls “singing my heart out beside the toilet bowl” when her microphone was put in it to achieve an echo effect. “It looked like chaos, but the music came out wonderful,” Motown saxophonist Thomas (Beans) Bowles mused recently.

Integrating symphonic strings with the rhythm band was another technique that helped Motown cross over from R&B to pop. When Gordy first hired string players, members of the Detroit Symphony Orchestra, they balked at requests to play odd or dissonant arrangements. “This is wrong, this is never done,” they’d say. “But that’s what I like, I want to hear that,” Gordy insisted. “I don’t care about the rules because I don’t know what they are.” Some musicians stalked out. “But when we started getting hits with strings, they loved it.”

The people who built Motown recall Hitsville in the early years as a “home away from home,” in the words of the Supremes’ Mary Wilson. It was “more like being adopted by a big loving family than being hired by a company,” the Temptations’ Otis Williams wrote. Gordy, a decade or so older than many of the performers, was the patriarch of the whole rambunctious bunch. When the music makers weren’t working they loafed on the front porch or played Ping-Pong, poker or a game of catch. They cooked lunch at the house—chili or spaghetti or anything that could be stretched. Meetings ended with a rousing chorus of the company song, written by Smokey Robinson: “Oh, we have a very swinging company / working hard from day to day / nowhere will you find more unity / than at Hitsville U.S.A.”

Motown was not just a recording studio; it was a music publisher, a talent agency, a record manufacturer and even a finishing school. Some performers dubbed it “Motown U.” While one group recorded in the studio, another might be working with the voice coach; while a choreographer led the Temptations through some flashy steps for a drop-dead stage routine, writers and arrangers might be banging out a melody on the baby grand. When not refining their acts, the performers attended the etiquette-and-grooming class taught by Mrs. Maxine Powell, an exacting charm school mistress. A chagrined tour manager had insisted the singers polish up their show-biz manners after witnessing one of the Marvelettes chomping a wad of gum while onstage.

Most of the performers took Mrs. Powell’s class seriously; they knew it was a necessary rung on the ladder to success. They learned everything from how to sit in and rise gracefully from a chair, to what to say during an interview, to how to behave at a formal dinner. Grimacing onstage, chewing gum, slouching and wearing brassy makeup were forbidden; at one time, gloves were mandatory for the young women. Even 30 years later, Mrs. Powell’s graduates still praise her. “I was a little rough,” Martha Reeves told me recently, “a little loud and a little undone. She taught us class and how to walk with the grace and charm of queens.”

When it came time to striving for perfection, no one was tougher on the Motown crew than Gordy. He cajoled, pressured and harangued. He held contests to challenge the writers to come up with hit songs. It was nothing for him to require two dozen takes during a single recording session. He would insist on last-minute changes in stage routines; during shows, he took notes on a legal pad and went backstage with a list of complaints. Diana Ross called him “my surrogate father . . . Controller and slave driver.” He was like a tough high school teacher, Mary Wilson says today. “But you learned more from that teacher, you respected that teacher, in fact you liked that teacher.”

Gordy instituted the quality-control concept at Motown, again borrowing an idea from the auto assembly line. Once a week, new records were played, discussed and voted on by sales people, writers and producers. During the week, tension and long hours mounted as everyone hustled to create a product for the meeting. Usually, the winning tune was released, but occasionally Gordy, trusting his intuition, vetoed the staff’s choice. Sometimes when he and Robinson disagreed over a selection, they invited teenagers in to break the impasse.

In 1962, thirty-five eager music makers squeezed into a noisy old bus for Motown’s first road tour, a grueling itinerary of some 30 one-nighters up and down the East Coast. Several shows were in the South, where many of the young people had their first encounters with segregation, often being denied service at restaurants or directed to back doors. As they were boarding the bus late one night after a concert in Birmingham, Alabama, shots rang out. No one was hurt, but the bus was peppered with bullet holes. At another stop, in Florida, the group disembarked and headed for the motel pool. “When we started jumping in, everyone else started jumping out,” Mary Wilson recalls, now laughing. After discovering that the intruders were Motown singers, some of the other guests drifted back to ask for autographs. Occasionally, or when, in the frenzy of a show, black and white teenagers danced together in the aisles, the music helped bridge the racial divide.

Though Motown was a black-owned company, a few whites recorded there and several held key executive positions. Barney Ales, the white manager of Motown’s record sales and marketing, was dogged in his efforts to move the music into the mainstream—this at a time when some stores in the country would not even stock an album with African-Americans on the cover. Instead of a photograph of the Marvelettes, a rural mailbox adorns their “Please Mr. Postman” album. In 1961, the single became Motown’s first song to occupy the number-one spot on the Billboard Hot 100.

Notwithstanding Ales’ success, it was three black teenage girls from a Detroit housing project who made Motown a crossover phenomenon. Mary Wilson, Diana Ross and Florence Ballard auditioned for Gordy in 1960, but he showed them the door because they were still in school. The girls then began dropping by the studio, honoring all requests to sing background and clap on recordings. Several months later they signed a contract and started calling themselves “the Supremes.”

Over the next few years, they recorded several songs, but most withered at the bottom of the charts. Then HDH merged plaintive singsong lyrics with a chorus of “baby, baby” and a driving beat, and called it “Where Did Our Love Go.” The record catapulted the Supremes to No. 1 on the pop charts and set off a chain reaction of five No. 1 hits in 1964 and ’65, all HDH compositions.

The young women continued to live in the projects for nearly a year, but otherwise their whole world changed. A summer tour with Dick Clark and an appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show were followed by other TV spots, nightclub performances, international tours, magazine and newspaper articles, even product endorsements. They soon traded their homemade stage dresses for glamorous sequined gowns, the dusty tour bus for a stretch limousine.

With the Supremes’ slicked-up sound leading the way, Motown proceeded to blaze a trail to the top of the pop charts, keeping pace with the Beatles, the Rolling Stones and the Beach Boys. Never mind that some fans complained that the Supremes’ music was too commercial and lacked soul. Motown sold more 45 rpm records in the mid-’60s than any other company in the nation.

Capitalizing on that momentum, Gordy pushed to broaden his market, getting Motown acts into upscale supper clubs, such as New York’s Copacabana, and glitzy Las Vegas hotels. The artists learned to sing “Put on A Happy Face” and “Somewhere,” and to strut and sashay with straw hats and canes. At first they were not entirely comfortable doing the material. Ross was crushed when a Manchester, England, audience started fidgeting while the Supremes sang “You’re Nobody ‘til Somebody Loves You.” Smokey Robinson called the middle-of-the-road standards “cornball.” Others were on unfamiliar territory, as well. Ed Sullivan once introduced Smokey and the Miracles thusly: “Let’s have a warm welcome for… Smokey and the Little Smokeys!”

By 1968 Motown had exceeded all expectations and was still growing. That was the year the company set up headquarters in a ten-story building on the edge of downtown Detroit. Four years later Motown’s first movie, Lady Sings the Blues, debuted. The story of Billie Holiday, played by Diana Ross, the film received five Academy Award nominations. Intent on further expansion into the film industry, Gordy moved the company to Los Angeles. Robinson had tried to dissuade him with a stack of books about the San Andreas Fault, to no avail. Gordy hungered to work his magic in Hollywood.

But the move to Los Angeles was the beginning of the end of Motown music’s golden era. “It became just another big company instead of the little company that thought it could,” Janie Bradford said recently. She started as a Motown receptionist, stayed with the company 22 years and even helped Gordy write one of his early hits, “Money (That’s What I Want).” After relocating, Gordy found little time for creating music or screening records. So much was changing. Lead singers left their groups for solo careers. Some wanted more creative and financial control. Gone were the house band and the cadre of young producers. Many of the performers, now famous, were being wooed away by other recording companies; some were disgruntled about old contracts and earnings, and complained that Motown had cheated them. Lawsuits ensued. Gossip and rumor would pursue Gordy for decades as the once most successful black-owned company in the country began a downward spiral.

Epilogue:

In 1988 Gordy sold Motown’s record division to MCA records for $61 million. A few years later it was sold again to Polygram Records. Eventually Motown merged with Universal Records and today is known as Universal Motown. Among the company’s recording artists are Busta Rhymes, Erykah Badu and Stevie Wonder.

The old Hitsville USA house in Detroit is now a museum and popular tourist destination.