Multiple Viewpoints

Photographer Edward Burtynsky’s politically charged industrial landscapes are carefully crafted to elicit different interpretations

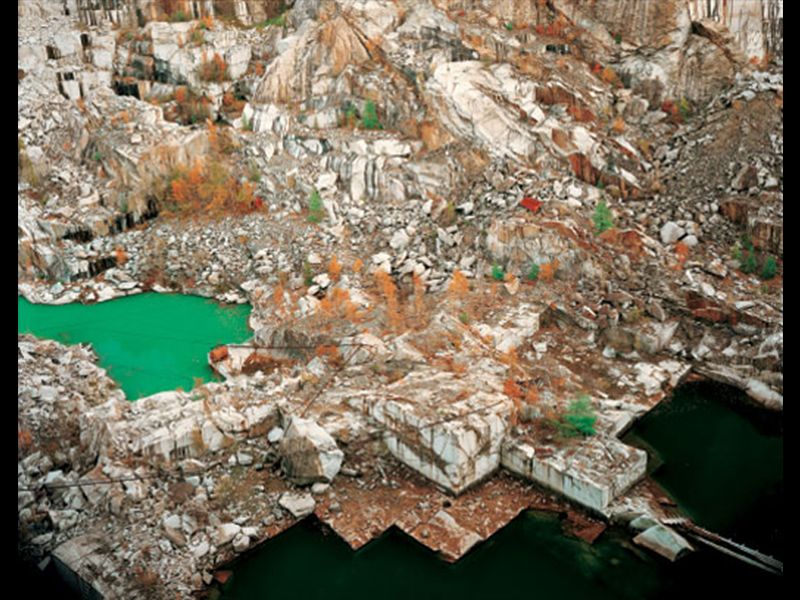

As a photography student at Toronto's Ryerson University in the late 1970s, Edward Burtynsky was struck by the scale of the city's skyscrapers and the powerful visual statements they made. Intending to pursue landscape photography, Burtynsky asked himself where in nature he might find places that had the same graphic power as these great structures. Thus began a career in pursuit of landscapes that also reflect the hand of man.

In contrast to the pristine views of landscapes found in national parks and distant preserves (exemplified by Ansel Adams and his photographic heirs), Burtynsky's work is more immediate—grittier. "The industrial landscape speaks to our times," he says. Which is why the 47-year-old Canadian's approach both seduces and repels. "I see my work as being open to multiple readings," he says. "One can look at these images as making political statements about the environment, but they also celebrate the achievements of engineering or the wonders of geology."

For example, his recent shipbreaking series from Bangladesh (where retired ocean vessels are run up on the beach at high tide and then furiously dismantled by workers in about three months) documents a process that leaves oil and toxic wastes on otherwise unspoiled beaches. Still, Burtynsky points out, the recycled metal is the country's sole source of iron, steel and brass. "I'm not using my art to browbeat corporations for the rack and ruin of our landscape," he says. "I'm trying to extract a slice out of that chaos and give it a visual coherence so that the viewer can decide."

Working as he does with large format cameras and their attendant paraphernalia puts special demands on the photographer. "My ticket to Bangladesh cost less than my overweight baggage fees," he notes wryly. Setting up a picture can take hours. "Sometimes you can move ten steps forward, or ten steps back, and the image just isn't there," he says. "But at some point it clicks in your mind."

Nor is the photographer's work done once the shutter is squeezed. "The ultimate experience for the viewer is an original print," he says, "thus I feel I need to pay strict attention to the printmaking." His fine-grain 50- by 60-inch photographs allow viewers to discover mundane artifacts, like a discarded stonemason's tool or the kaleido- scope of labels and logos from cans compressed in a crusher.

Burtynsky sometimes uses telephoto lenses to compress the foreground and get the viewer to the heart of the matter. "It's in this middle ground that you experience the sweep of the landscape," he says.