Museums With Their Own Niche

Subjects as wide-ranging as lunchboxes, roller skating, and Bigfoot have museums dedicated solely to their study and appreciation

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Velveteria-631.jpg)

I peered at the rows of lunchboxes and stopped with a smile in front of a gleaming Strawberry Shortcake, its pink and white figures recalling peanut butter and jelly sandwiches, piles of crayons and an overnight party where at least one lucky girl unrolled a Strawberry Shortcake sleeping bag. I wondered if one of these lunchboxes was still hidden in the dusty recesses of my house. In an instant, a tall man with hair like gray steel wool was at my side.

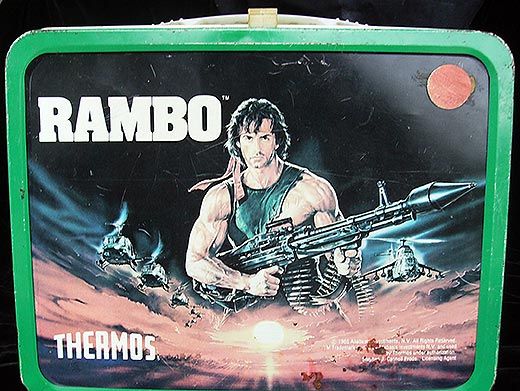

“Ah, you’re of the metal lunchbox era!” said Tim Seewer, artist, cook and partner in Etta’s Lunchbox Café and Museum in New Plymouth, Ohio. “The Florida Board of Education decided in 1985 to ban metal lunchboxes because they could be used as a weapon. All across the United States, lunchboxes started to go plastic. Ironically, the last metal lunchbox was Rambo.”

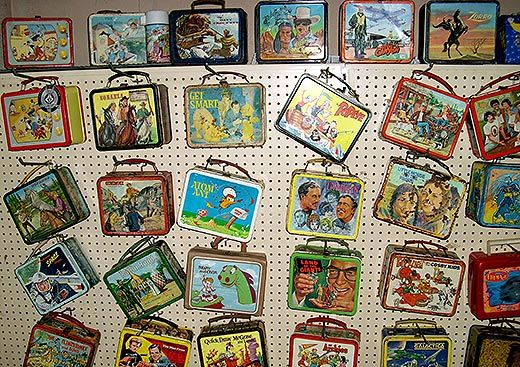

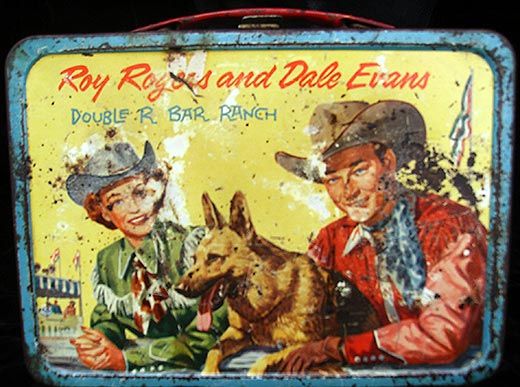

Etta’s is a thoroughly charming bit of Americana. Lodged in an old blue-tiled general store, this free museum displays owner LaDora Ousley’s collection of 850 lunchboxes as well as the tobacco and lard tins that were the precursors to the lunchbox. The collection offers a unique lens into the popular culture of the last century—especially when accompanied by commentary from Seewer and Ousley, who do double time in the kitchen making pizza, sandwiches and salads. A 1953 Roy Rogers and Dale Evans lunchbox, the first to have a four-color lithograph panel, is among the collection’s notable items. Also on display are lunchboxes featuring the many television icons that followed: Gunsmoke, Looney Tunes, a host of Disney characters, Popeye, Space Cadet, the Dukes of Hazzard, and more.

The collection both chronicles the stories and characters that shaped many a childhood and offers a perspective on larger social trends in America. As an example, Ousley points to her tobacco tins, which were produced beginning in 1860 with sentimental domestic scenes on them. “It was a clever cross-marketing ploy,” Ousley explains. “Women weren’t allowed to buy tobacco, but it was a sign of status to own one of these tins. It showed you knew a man wealthy enough to buy one and that you were special enough to receive it as a gift.”

Museums with a singular focus—whether on an object or a theme—offer visitors an intimate educational experience, often enhanced by the presence of an owner or curator with an unmatched passion for the subject. Here are seven more narrowly focused museums from around the country, some tiny and precariously funded, others more firmly established.

Velveteria, the Museum of Velvet Paintings in Portland, Oregon, has nearly 2,500 velvet paintings at last count. Eleven years ago, Caren Anderson and Carl Baldwin were shopping in a thrift store, spied a black velvet painting of a naked woman emerging from a flower and had to have it. That impulse buy ultimately led to a vast collection, much of which is now displayed in an 1,800-square-foot museum. Co-authors of Black Velvet Masterpieces: Highlights from the Collection of the Velveteria Museum, Anderson and Baldwin have a connoisseur’s eye for this neglected art form and an appreciation for its history. The paint-on-velvet form had its origins in ancient China and Japan, enjoyed some popularity in Victorian England, then had its modern heyday when American servicemen like Edgar Leeteg expressed the beauty they saw in the South Seas islands on black velvet. You can tour the museum for $5.00, but watch out for unexpected emotion. “A young couple got engaged in our black light room the other day,” says Anderson.

The National Museum of Roller Skating in Lincoln, Nebraska, boasts 2,000 square feet of memorabilia from roller derby, roller speed and figure skating, and roller hockey. Included are a pair of the first skates ever made, which resemble modern inline skates, patent models from the history of roller skate design, costumes, trophies, photos and magazines on skating. Oddest items: a pair of skates powered by an engine worn on the back and a pair of skates made for a horse—with a photograph of the horse wearing them. This is the world’s only museum devoted to roller skating; admission is free.

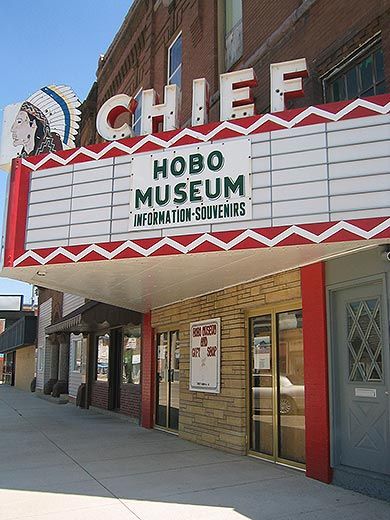

The Hobo Museum is located in the hobo capital of the world, Britt, Iowa. According to curator Linda Hughes, the town fathers of Britt tossed out a welcome mat for hoboes in 1899 after hearing that Chicago rolled up theirs when Tourist Union 63—the hobo union—wanted to come to town. A famous hobo named Onion Cotton came to Britt in 1900, and hoboes have been gathering there ever since. The museum is currently housed in an old movie theater, but has so much material it plans to expand into a larger space. The collection includes contents of famous hobo satchels, a hat adorned with clothespins and feathers from Pennsylvania Kid, tramp art, hobo walking sticks, and an exhibit of the character language hoboes use to leave each other messages. Every year, Britt and the museum host a hobo convention that attracts up to 20,000 ramblers from all parts of the country. “It’s like a big family reunion,” Hughes says.

The Museum of Mountain Bike Art and Technology Museum is located above a bike store in Statesville, North Carolina, with a 5,000 square-foot showroom displaying the evolution of mountain bikes. The collection includes “boneshakers”—bikes from 1869 with wooden spoke wheels—as well as bikes with interchangeable parts from the turn of the century. Among this free museum’s 250 bikes are several from the mountain bike boom beginning in the 1970s, when the energy crisis pushed people to make tougher bikes. Many of these are highly designed with great craftsmanship. “Even if you have no interest in bikes, you’d hang one on the wall because they’re so pretty,” says owner Jeff Archer. The museum holds an annual mountain-bike festival that attracts many of the sport’s pioneers.

The Bigfoot Discovery Museum in Felton, California, was inspired by owner Michael Rugg’s encounter with a Sasquatch-like creature when he was a child. The museum offers local history tied to Bigfoot; plaster casts of foot and hand prints; hair, scat and tooth samples; displays that discuss hypotheses to explain Bigfoot sightings and Bigfoot in popular culture; and a research library. In the audio-visual section, the controversial Patterson-Gimlin film purporting to show a Bigfoot spied in the wild runs on a continuous loop. “I’ve got everything I’ve found dealing with Bigfoot or mystery primates here,” Hughes says.

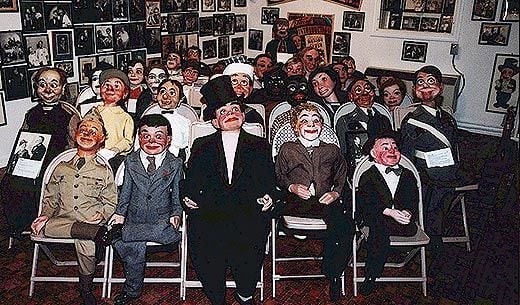

Vent Haven Museum in Fort Mitchell, Kentucky, is the world’s only public collection of materials related to ventriloquism. A Cincinnati businessman named William Shakespeare Berger and later president of the International Brotherhood of Ventriloquists began the collection in the early 1900s; ventriloquists—“vents”—still donate materials. There are 700 ventriloquist dummies arranged in three buildings, some sitting in rows as if waiting for a class to begin. Unusual creations include a head carved by a German prisoner in a Soviet POW camp from World War II—the vent performed for fellow prisoners as well as for the cook to get extra food—and a family of figures used by a blind Vaudeville-era vent. Photographs and drawings of vents abound, including one from the late 1700s, when ventriloquism was more often a trick to con people out of money instead of a form of entertainment. The museum also has a library with 1,000 volumes and voluminous correspondence for scholars. Admission is by appointment only, and curator Jennifer Dawson leads hour-and-a-half tours for $5.00. A yearly convention is held nearby.

The Robert C. Williams Paper Museum in Atlanta originated with a collection by Dard Hunter, an artist from America’s Arts and Crafts Movement who traveled the world to record the ways that people made paper and collect artifacts. In the museum, visitors can examine precursors to modern paper, including many tapa cloths made from pounded bark in Sumatra and Tunisia with inscriptions from special occasions; a vat used by Chinese papermakers in 200 B.C.; and one of the one million prayers printed on paper and enshrined in wooden pagodas that were commissioned by the Empress Shotuku after Japan’s smallpox epidemic of 735. In all, there are over 100,000 watermarks, papers, tools, machines and manuscripts. Admission for individuals is free; guided tours are $5 per person or $8.50 for a tour and paper-making exercise.