Music for Airports Soothes the Savage Passenger

Brian Eno’s Music for Airports is a sound environment created specifically to complement the experience of waiting in an airport terminal

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Ambient-hero.jpg)

Airports are stressful places. That’s why I take red-eye flights whenever possible. There’s just something romantic about sitting in a nearly empty airport, staring out 30-foot-high windows as you wait to travel to a new city. Or, better, sitting at the airport bar, drinking overpriced cocktails and whispering your darkest secrets to a complete stranger, safe in the knowledge that you’ll never see them again. The quiet peacefulness of an airport in the middle of the night contrasts distinctly from daytime, when the miracle of human flight is likely to be sullied by terrible service, long lines, incessant delays, crowds camped out around power outlets and the sound of thousands of passengers rushing loudly through the terminal.

It is with this anathematic environment in mind that in 1978 musician Brian Eno created the seminal album Ambient 1: Music for Airports. Eno’s project began while waiting for a flight at an airport in Cologne, Germany, on a beautiful Sunday morning. “The light was beautiful, everything was beautiful,” Eno recalls, “except they were playing awful music. And I thought, there’s something completely wrong that people don’t think about the music that goes into situations like this. They spend hundreds of millions of pounds on the architecture, on everything. Except the music.” The realization launched Eno on an artistic mission to design sound environments for public spaces. When he sat down to actually compose the score, Eno envisioned the empty airport that I find so compelling: “I had in my mind this ideal airport where it’s late at night; you’re sitting there and there are not many people around you: you’re just seeing planes take off through the smoked windows.”

Los Angeles International Airport at night (image: wikimedia commons)

Music for Airports opens with the tapping out of single piano keys over an unidentifiable, warm sound texture—or maybe it’s just static. The notes start to overlap, richer tones begin to echo in your ears. Then silence, just for a moment, before the piano starts back up, now accompanied by what sounds like the gentle strum of a space cello or the resonance of a crystal wine glass. The notes start to repeat. Then overlap. Then silence. Now cue the whispering robot choir.

It’s at once haunting and comforting. The ebbs and flows of the minimalist composition are slow and deliberate; sonic waves lapping at the beach. Eno coined the term “ambient” to describe this atmospheric soundscape and distinguish it from the stripped-down, tinny pop songs pioneered by Muzak—which certainly have a charm of their own, although they are decidedly less soothing. In so doing, he created not just an album, but an entire genre of music. Eno elaborates on the nature of ambient music in the liner notes Ambient 1: Music for Airports:

“Whereas the various purveyors of canned music proceed from the basis of regularizing environments by blanketing their acoustic and atmospheric idiosyncracies, ambient music is intended to enhance these. Whereas conventional background music is produced by stripping away all sense of doubt and uncertainty (and thus all genuine interest) from the music, ambient music retains these qualities. And whereas their intention is to ‘brighten’ the environment by adding stimulus to it (thus supposedly alleviating the tedium of routine tasks and leveling out the natural ups and downs of the body rhythms) ambient music is intended to induce calm and a space to think.

Ambient music must be able to accommodate many levels of listening attention without enforcing one in particular; it must be as ignorable as it is interesting.”

It must be as ignorable as it is interesting. No small order. The amount of creativity and thought that went into the design of Music for Airports is inspiring. Ambient music could have no discernible beat or rhythm. It could not interfere with conversations, so it had to be higher or lower than the pitch of the human voice. It had to be played for long periods of time while also allowing for periodic interruptions and announcements. All these requirements were considered as Eno constructed his album from tape loops and highly-processed snippets of audio excerpted from an improvisational recording session.

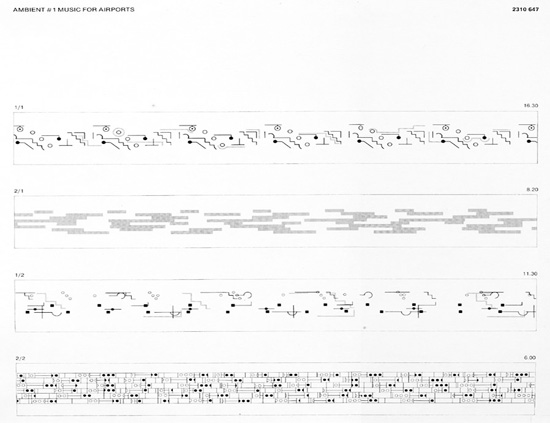

Brian Eno's graphic notation for Music for Airports, published on the back of the album sleeve

Goethe famously described architecture as “frozen music.” One shudders to think of a true physical manifestation of cacophonous airport noise: canned voices mumbling over an intercom, the incessant clicking of heels on tile floors, alarms, horns, the blaring of canned television news segments, the general hum of people and technology that exists in these strange liminal micro-cities of departure and arrival. Actually, perhaps airports are the physical manifestation of that noise: disorienting structures of metal and glass, at once familiar and unique, whose vast corridors become destinations themselves. In this spatialized white noise, Music for Airports is a phenomenological balm; a liquified counter-architecture.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jimmy-Stamp-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jimmy-Stamp-240.jpg)