The Neuroscientist in the Art Museum

At Massachusetts’s Peabody Essex Museum, Tedi Asher is using neuroscience research to create impactful art experiences

:focal(1658x1390:1659x1391)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/52/47/52470cec-bcf9-477c-93a5-de0df1f465b2/20170283_6066-full_jpg.jpg)

They were wired up with eye-tracking glasses and biometric sensors. The former would capture where they were looking. The latter would measure how much their skin produced sweat in response to a particular experience.

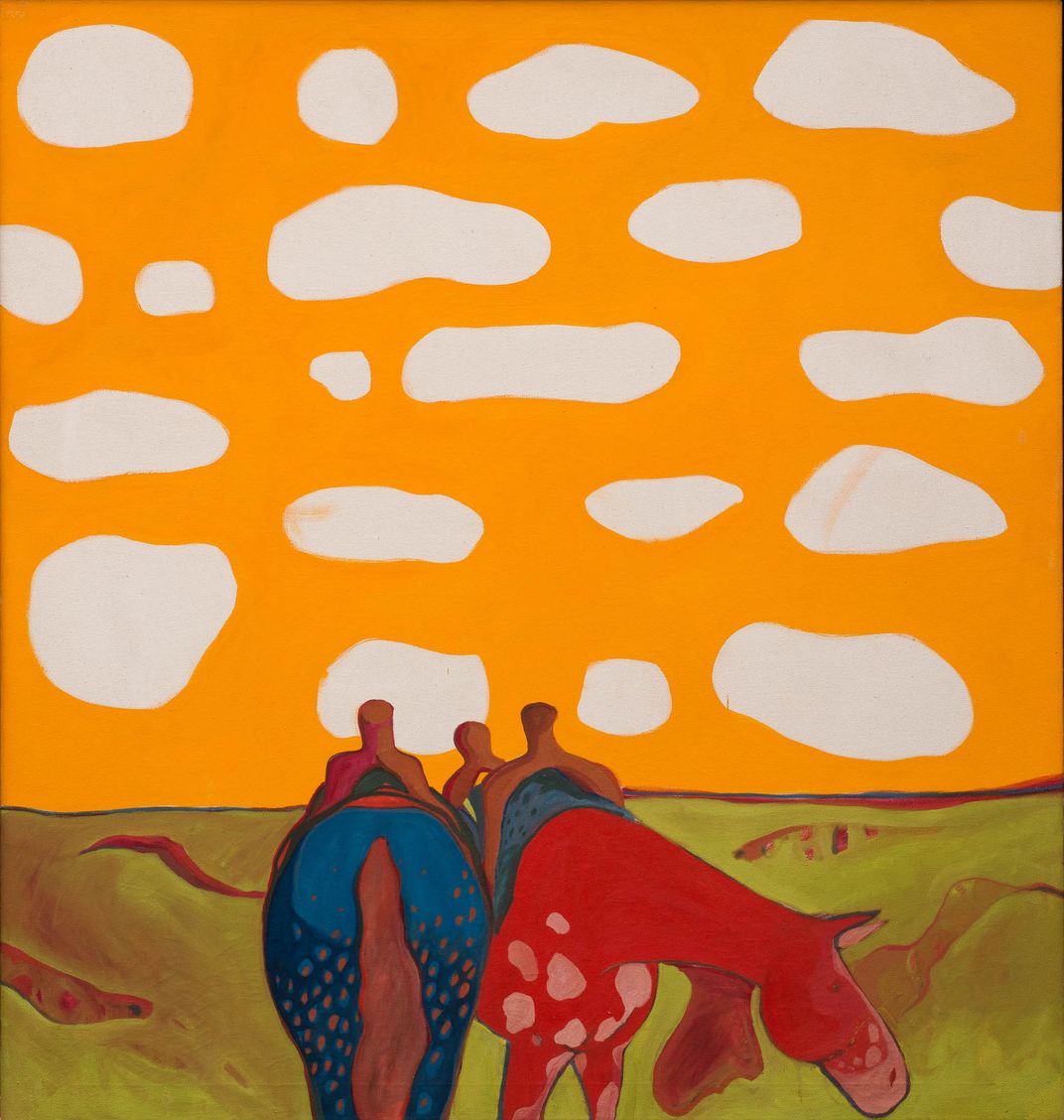

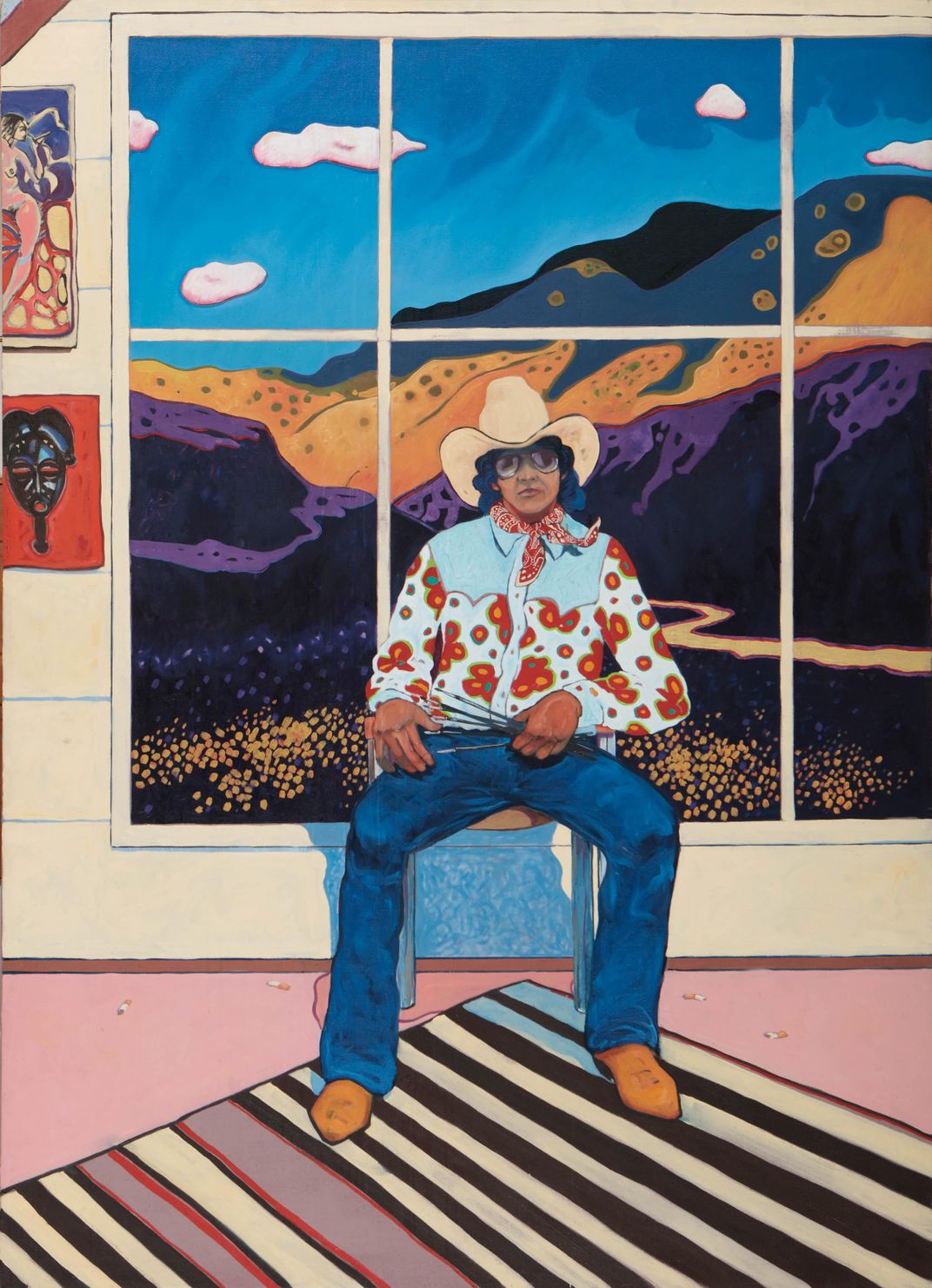

The subjects weren’t in a lab — at least not in the traditional sense. They were visitors to the Peabody Essex Museum’s spring exhibition “T.C. Cannon: At the Edge of America,” which explored the 20th-century Native American artist’s impact on art, music and poetry. During their time in the show, the participants were each given one of three viewing tasks. The intent was to see if the prompts might get them to engage with the art in a different way.

As Tedi Asher, the Salem, Massachusetts, art museum’s neuroscientist-in-residence explains, museum visitors aren’t necessarily viewing art the way they might think they are.

“Sometimes our conscious experience of things does not always reflect our physiological response to something, or our behavioral response,” says Asher.

It’s been a little over a year now since she was first brought on board at PEM, and the T.C. Cannon experiment was the fruition of her first full-scale research project to take place at the museum. With the experiment, she is seeing how neuroscience research can improve the art museum experience.

To find out why an art museum is turning to the field of neuroscience to inform its exhibition space, one only needs to look to Dan Monroe, who has been the director of the museum since 1993, the year after the museum was born out of the merger of the Peabody Museum of Salem and Essex Institute. Since taking on the helm, he’s sought to position PEM as an art museum for the 21st century.

“We've done that largely by being innovative,” he says. “We're idiosyncratic. Whichever way you prefer to describe it, we take pride in constantly questioning how we do things at PEM or how they're done in our field.”

Monroe is conversant in everything from quantum mechanics to evolution to cosmetology, and then can connect it all to the state of uncertainty that art museums across the country are currently facing.

In the past two decades, there’s been a marked decline in attendance at art museums nationwide. Looking at 2015 visitation numbers in comparison to 2002, the Baltimore Sun crunched data from the National Endowment for the Arts earlier this year to suggest there’s been, in fact, a 16.8 percent drop during that time.

“The fact is, the culture is changing dramatically,” says Monroe. “When asked what people want out of cultural activities today, and this is across all age ranges, the number one priority people want is fun,” he says, in reference to findings from the 2017 Culture Track study, which listed fun as respondents’ “single greatest motivation” for attending cultural activities. “That's not what we were all thinking about five or six or 10 years ago as the most important criterion for the success of a cultural event or activity, and what fun means is obviously an interesting question,” he allows, “but the whole definition of culture is changing, and the idea that cultural organizations are immune from the incredible changes that are occurring— at dramatically faster speed than ever before— would be incredibly dangerous and naive.”

Monroe holds that museums today are facing an inflection point, and they must question standard museum pedagogy. For instance, is it actually best to present art in a white box gallery space? The museum director says that institutions need to continually develop new approaches if they want to stay relevant.

“Everyone in the museum world wants to create experiences that really have an impact on people,” he says, “otherwise why would we be dedicating our lives to the work that we do? But if we're doing things that in reality don't work really well then we're really undercutting ourselves and we're undercutting the role and importance of art.”

Following that train of thought, around four years ago, inspired by books like Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow, he began to think about how neuroaesthetics might fit into that conversation. In retrospect, he says, “this unbelievably obvious idea” struck him. If you accept the premise that the brain creates all experiences— including art experiences— then the logical next step for PEM was simple: “If we want to create more meaningful, relevant and impactful art experiences,” says Monroe, “it probably would be a better idea to understand how brains work.”

After securing funding from the Boston-based Barr Foundation (which has recently adopted a more public-facing profile in the nonprofit world for its arts funding grants), PEM opened up applications to find a full-time neuroscientist. The job posting did not specify any particular branch of neuroscience. Instead, it was a broad call for someone with a graduate degree in the field who could work to identify and apply research from neuroscience to the design of art exhibitions and to study how people experience art. To Monroe’s knowledge, the museum residency was the first of its kind.

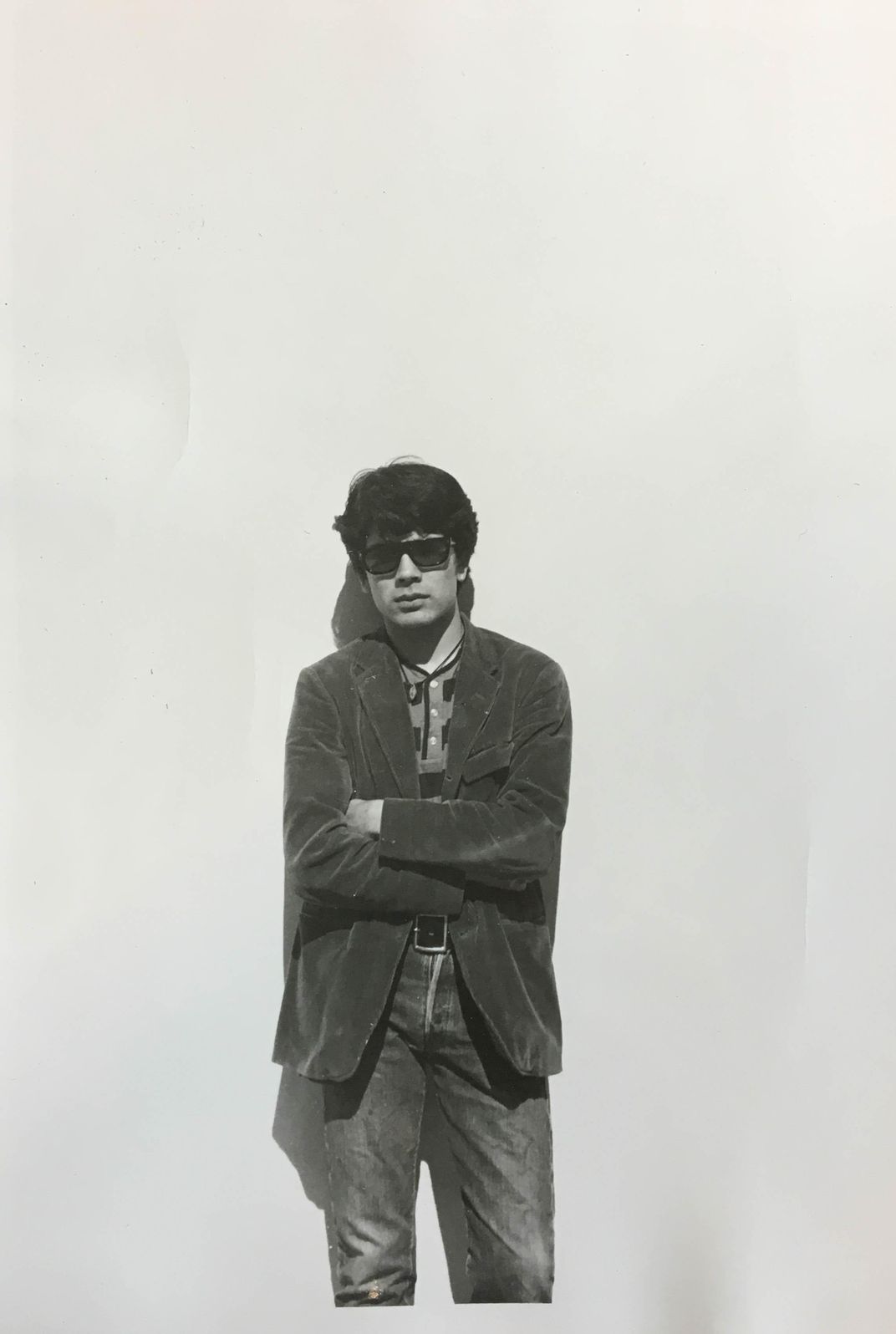

Asher’s application stood out. She had focused her doctoral work at Harvard Medical School’s Biological and Biomedical Sciences on studying aggressive behavior in rodents through manipulating a population of neurons in their brains. While she did not have a formal background in the arts, she came from a family full of artists and spent a lot of time in museums growing up in Washington, D.C. When she accepted the position in May 2017, she particularly impressed the museum with her ability to move from the culture of the neuroscience community to that of the art world. “Not anyone could make that transition, and she did it seamlessly,” Monroe says.

Initially, Asher was slated to stay on for a 10-month residency, but another grant from the Barr Foundation has secured funding for her work for a total of three years.

“When I first got to PEM,” says Asher, “we knew what the objective was, which was to create more compelling exhibitions for our visitors, by drawing on findings from the neuroscience literature, but we didn't know exactly how to do that.”

Over time, she’s developed a three-step approach, starting with the research and hypothesis phase, where she’ll go through the literature for findings relevant to exhibition design. From there, she will identify a hypothesis with her colleagues about how to apply those findings. Then, they’ll work to devise a test, like what emerged in the T.C. Cannon exhibition.

The museum established an advisory committee to support Asher’s work. During their initial meeting, one of the advisory board members, Carl Marci, of Nielsen Consumer Neuroscience, which applies the field of neuroscience research to the marketing world, got the conversation started on how to study museum engagement, something he had already set out to define from a consumer neuroscience perspective, and which folded neatly into PEM’s own mission statement, which seeks to create “experiences that transform people's lives.”

Marci breaks engagement down into three facets: attention, emotion and memory. Attention comes first, he says, because “you can't process anything you're not paying attention to.” But because people pay attention to many things they don't remember, he theorizes that the event needs to trigger an emotional response, one that must be significant enough, he says, to meet the threshold that allows it to “lay down a memory trace and influence you down the road.”

“I think my job is very much about, okay, well how do we do that,” says Asher. “What are the factors that influence attention allocation in a setting like a museum? What is emotion? How do you break it down? How do you measure it? How do you elicit it in different ways? Then, how does that relate to the formation of a memory? And, what are the different ways that we can measure the changes that are induced by creating that memory, either behaviorally or physiologically, or verbally?”

These are questions that a museum could debate for years on a philosophical level. But on a neuroscience level, they become quantifiable variables to be hypothesized and tested.

“I see myself as very much like the mechanic,” Asher says. “Like, how do we take all of these parts and work with them in a way that we're facilitating engagement?”

Leading research in the field suggests that emotional arousal—how intense an experience is—may be the key to forming a lasting memory. So, says Asher, “If there's a particular area in an exhibition that we would like to really stay with visitors, we know we need to make it emotionally quite intense.”

How to create that emotionally intense experience is, of course, a more complicated question, but it’s one that Asher dug into in the T.C. Cannon experiment.

Back in the 1960s, Russian psychologist Alfred Yarbus pioneered a device that could precisely track eye-movement. In his research, Yarbus demonstrated that if subjects were given specific viewing instructions, their eye-movement pattern varied accordingly. Psychologist Benjamin W. Tatler would build on this research to demonstrate the converse: if subjects were given no specific viewing instructions, their eyes would gravitate toward the focal point of the image.

Asher built her experiment from this body of research, as well as work in neuroaesthetics that explores how we respond to art. In a 2012 study, lead author Ed Vessel coupled fMRI scanning to track brain activity with behavioral analysis to research what makes people respond to artwork. He concluded that aesthetic experiences involve “the integration of sensory and emotional reactions in a manner linked with their personal relevance.”

With the T.C. Cannon exhibit, Asher hypothesized that by priming museumgoers with specific viewing goals that ask them to consider how they’re personally impacted by the artwork, they will look at the art in a way that will promote greater engagement with the works.

To test this idea, back in May Asher worked with the curator of the exhibition, Karen Kramer, to identify nine artworks in the show and develop prompts for three different groups of viewers. Test subjects in one group were just given a historical fact about the art, to stimulate what’s called “free viewing” of the works. Subjects in a second group were directed to find a particular element in the piece—a searching task. And participants in a third group made a judgement about the work, after being asked a personal question about it. The 16 total participants in the experiment, which was conducted over the course of two weeks, were all given exit interviews when they left the exhibition to learn how they thought they engaged with the art.

Over the course of the summer, Asher will take this data and evaluate their eye movements, their sweat and their own impressions of the experience. The idea is to see if the group assigned the personal reflection prompt —the judging task — responded more strongly to the exhibition in comparison to the other two groups.

There’s something that might feel a little unsettling about the premise that the way people respond to art can be altered based on the way it is presented, and that an art museum would, in fact, even want to do that. But as Asher points out, the idea is not to manufacture a common experience—something she says is not only not a desirable result, but also not even a realistic one. “There are too many idiosyncratic things that each individual brings with them when they come to a museum,” she says. “Those memories, and experiences, and associations are things to be valued and they're things that will really impact how people relate to the art, and that's great.”

Instead, the hope is to make the museum experience as effective as possible. “If we’re doing things that in reality don't work really well then we're really undercutting ourselves and we're undercutting the role and importance of art,” says Monroe.

Elizabeth Merritt, founding director of the American Alliance of the Museums’ Center for the Future of Museums, who is not associated with PEM, says that Asher’s work actually follows a long tradition of bringing outside perspectives to bear on the museum experience. Back in 1992, the Maryland Historical Society in Baltimore invited African-American artist Fred Wilson to rethink its collections. Wilson went through the museum’s storage and selected objects for his Mining the Museum installation that highlighted the underrepresented contributions of African-Americans, Native Americans, women and other groups to Maryland’s history. He positioned, for instance, a 19th-century armchair next to slave shackles and a whipping post.

“I think that was the premier example that really caught the attention of the museum field,” says Merritt. “Like, wow, there are people who see what we do differently and can come in and take our stuff and come up with completely different narratives equally or more true that would help people really change how they think about history and see what we are as a museum.”

She cites other examples of residencies, like the Harn Museum of Art’s poet-in-residence or the Dallas Museum of Art’s writer-in-residence, which reflect a larger willingness among museums to look outside of the traditional fields of art to inform their spaces. While integrating individuals with hard science backgrounds into the art museum space is a little rarer, there are some to be found, like the School of the Art Institute of Chicago’s scientist-in-residence program, which began in the spring of 2014.

PEM, Merritt says, is, in fact, the second art museum she knows of to explore art through the lens of neuroscience. Back in 2010, Gary Vikan who served as the long-time director of the Walters Art Museum began a fruitful collaboration with Johns Hopkins University’s Zanvyl Krieger Mind/Brain Institute. Notably it produced “Beauty and the Brain,” an exhibit that also turned museumgoers into test subjects, asking them to analyze which drawings of abstract sculptures by 20th-century artist Jean Arp were most pleasing to the eye. Vikan called artists “instinctive neuroscientists” in an interview with the Baltimore Sun at the time.

“In general, all of these interdisciplinary approaches are ways to provide new points of entry to diverse audiences,” says Merritt. “Some people could be reached by poetry or music in ways they wouldn't necessarily respond visually to art. It's a way for them to have a new entry point.”

But at the same time, she says, having a full-time neuroscientist on board at an art museum is breaking new ground.

“I think that together we're all trying to figure out like, ‘Okay, what is this and how do we incorporate this approach in?” says Asher, who is already thinking ahead to her next experiment, which she is not ready to comment on at this time.

Right now, neuroscience remains a new frontier for informing museum doctrine. But she could be on the frontlines of a shift.

If the modern field of neuroscience is said to have crystallized at the turn of the 20th century, revolutionized by thinkers like Spanish artist and scientist Santiago Ramón y Cajal, it could very well be that the 21st century is when we see a wide range of research findings actually applied in the real world.

What that means for museums, art museums specifically, is still being articulated. In the world of marketing communication, Marci says, at there’s at least a clear message tied to a brand tied to a goal, like purchasing a product. “I think museums have broader goals in terms of having experiences with people and expanding their views of the world,” he says, something that he believes makes Asher’s work both a challenge and an opportunity.

How do you create the frameworks to measure people having experiences? And what is the end goal? Is the idea to just provoke an emotional reaction? Or is the idea to change a visitor’s point of view on a topic presented? “Once you can begin to measure things, you can actually ask very different questions,” Marci says. “I think that's exciting and a little intimidating.”